Self-Portrait at the Age You Are

The time I tried to get David Berman published in the Oxford American, and other notes

In late summer 2019, just after we moved to Jersey City, we decided to see David Berman play at White Eagle Hall, a recently restored club near downtown that looked a little bit like an old Masonic Temple (in fact, it used to be a community center that hosted weekly bingo and “battle of the bands” competitions, etc.)

Berman, once the frontman of the Silver Jews, now had a new band that went by Purple Mountains. We were obsessed with their new single, “All My Happiness is Gone.”

It had just come out that year, and we played it over and over again, including on our long drive to move from Florida to Jersey. You know that feeling? When you hear a new song, and there is something about it, something so perfectly satisfying that you want to hear the beginning again precisely after you have heard the end? Like you just want to hang on to that particular frame of being in the world?

Our daughter dug it, too, and she would ask us to play it on repeat. She just called it “happiness” and she would sing: “All my happiness is gooooooone.” It was sweet.

And then one day in August, I got the news from social media, perhaps, or maybe from a friend. I don’t remember, but I do remember that on that particular morning, my daughter had woken up singing that song.

The news was this: A few days before that scheduled show in Jersey City, David Berman took his own life.

That fact hangs over everything about Berman’s life. There is no way around that. But this is a light story. He had, by all accounts, a heavy life. But it was still a life, and like any life, sometimes it was light. Sometimes it was funny; sometimes it was sweet.

I saw the Silver Jews play a few times. The first time was in Atlanta, back in 2006. I drove there from Gainesville, Florida, to see them. I can’t recall if this was partly a legend or entirely the truth, but the Silver Jews had never toured prior to this. Already a band with a cult following, this added to the mystique. For their flock, seeing them finally perform live was something like a pilgrimage. “This is our second show ever,” Berman told us in Atlanta. “We’re going to do the best we can.”

A music stand with a clip-on light propped up a messy stack of lyric sheets. The performance was loose and ungainly. Even with the music stand to help him, the crowd had a closer grasp on the words to the songs than Berman did. But it worked. He seemed slightly shocked by the spectacle of his devoted fans, unmoored by just how excited other human beings were to watch him perform. “You’re gonna make me compliment you,” he told the crowd, “but I’m not that kind of guy.” Sounds like a line from one of his songs.

For the record, I don’t remember any of this. I remember vaguely the darkness of the club. I remember roughly where I was standing in relation to the stage, perhaps thirty feet away and a little to the right.

The only reason I have access to more detail than that—to the tenor of my reaction, to a few of the songs that were played, to the atmospherics and the crowd—is because I happened to review the show for No Depression, an alt-country magazine that I loved back then. The description above is cribbed from that article. It was a short little review, itself totally forgettable, but somewhat to my surprise it still exists online. I was just shy of 28 when I wrote it. So now I have a few notes from that time I can read today, as if receiving a brief letter from a past self. It’s a good idea to write things down, to keep the records. You wouldn’t believe, at 28, how much you’ll forget.

Berman was a fan of Johnny Paycheck, our featured singer on Honky-Tonk Weekly this week. In a July 2019 interview with the Ringer promoting the debut Purple Mountains album, Berman explained:

It’s unbelievable how disrespected he is. And it’s because of “Take This Job,” which became like the country-music “Who Let the Dogs Out?” I love him. … I don’t know. He wasn’t much of a writer. He’s a dumb fuck, as anti-intellectual as it gets. There’s not much to like about him as a person. But there’s 10 or 15 songs of his that I put above all other music. I relate to him as an outsider. His voice is so moving. The tear in his voice.

The italics in the transcription only make me wonder more whether he meant the word about crying or the word about something ripped apart.

I was vaguely aware of Berman’s interest in Paycheck, but the connection was brought home to me by a lovely essay recently in the Oxford American by Rebecca Bengal. They were very different singers, but they had an interest in some of the same terrain, perhaps. Both try to “assuage the most cosmic, bizarre, and mundane aspects of the universe and attempt to reckon with them all on an equal emotional register,” Bengal writes. “But the material world is forever at awkward odds with the spiritual, and their failure to converge produces the comic gap between the banal and the sublime.”

I temporarily forgot what “assuage” meant, or at least doubted myself, and looked it up—and there it is, the perfect word.

If you wanted a bumper sticker, or a fortune cookie message—which Berman or Paycheck might have preferred—it could read: Life is clumsy and sometimes bleak, lol. Or perhaps the proper mode for this brand of reckoning is in fact the dopey zen of a certain sort of country song. A friend once suggested that a good country line would be, I’m just sitting around here waiting for you to not be gone. Not bad. “Honk if you’re lonely tonight,” Berman sang. Or: “I wish they didn’t put mirrors behind the bar / Cause I can’t stand to look at my face when I don’t know where you are.” Self help is a rough business for those of us selves in need of help, even if the particulars are mundane, and kind of dumb sometimes.

Here’s Bengal:

Country songwriting has long leaned on exaggerated metaphors, the tropes of the down and out, underdogs and the tear in the beer, but often with a veil of irony. Lift that and you have a song like the Silver Jews’ “Honk If You’re Lonely,” from American Water, which lends a jagged, lovely, bittersweet melody to a bumper sticker platitude. If you can picture a door that swings open between love and bleak loneliness, between the existential and the comic, between the mystic and the familiar, Paycheck and Berman worked its hinges.

So if they shared terrain, this is our terrain. “It’s been evening all day long,” Berman sang. That one he sort of stole from Wallace Stevens. Good steal though.

Bengal’s piece also reminded me that Berman was a periodic blogger—he had shared a few songs from Paycheck on metholmountains, the curious blog he had kept since 2011 (at times semi-frequently, at times with no posts at all for a few years).

It’s hard to describe mentholmountains, which was on Blogspot, and had the janky, slapped-together look of early blogs, an aesthetic that almost feels like an inside joke given Berman’s slacker-forward roots. The blog rarely had any hint of a bloggy voice—of Berman speaking to you as I am speaking to you now. He mostly shared quotes, readings, songs, links, lists, newspaper clippings, found writings—with arch commentary, sort of, in deadpan titles or the text for links.

Because it’s Berman, it congeals, if you’re feeling generous, into a shambolic poetry. Berman was always a collage artist and the internet was fertile ground. So there’s posts like “Northwest Indiana Punk 2009-2016 was Hot as Hell” and “Names I’ve Found Difficult to Pry Apart; Thinking Two People Are One or Thinking Two People Are Eachother,” and so on. He was fond of long lists of links, say to obscure texts or Youtube videos, with saucy (and straightforwardly accurate) descriptions of each. One post linked to articles in peer-reviewed academic journals on “orangutan menopause,” “kansas city skywalk collapse,” “female country music 1980-1989,” “schadenfreude in young children,” “the peacefulness of chinese teenagers,” “consuming hot peppers after anal fissure surgery,” “italian clinic clowns and the self-to-clown persona shift,” and around thirty others. My favorite from 2019 was a post called fyi: other david bermans, which just lists and give brief descriptions and links for other people named David Berman.

The blog was personal but baffling, like eavesdropping with insufficient information—a reading list, the brief summary of daydreams. This sub-voyeurism feels even stranger now. He’s dead. The blogspot is still here.

A number of his final posts featured long passages or quotations from Thomas Bernhard. A sample from what would turn out to be Berman’s final post, on July 26, 2019, from an interview with Bernhard:

Q: You're always presented as a kind of loner in the mountains, the man from the farm...

A: What can you do. You get a name, you’re called “Thomas Bernhard”, and it stays that way for the rest of your life. And if at some point you go for a walk in the woods, and someone takes a photo of you, then for the next eighty years you’re always walking in the woods. There’s nothing you can do about it.

Anyway. Reading about David Berman in the Oxford American made me think about the time I tried to get him to write for the Oxford American.

So here’s the story. Or maybe it’s something less than a story. Call it half a verse, out of context, for a missing song.

For the first fifteen months after college I drove around the United States and Canada. Then as my first real job, I got hired in fall 2002 as an intern making minimum wage at the Oxford American, which was my favorite magazine at the time. I believe after the first issue that we put out, we interns got promoted to something like assistant editor and got a pay bump of maybe another two or three bucks an hour. This was actually more money than we needed, Little Rock was cheap. More or less right away, we got to work directly with writers we were smitten with. I spent a good deal of time fruitlessly researching whether we could come up with an exact count of the number of blind bluesman that had ever been recorded, which the editor in chief really wanted to know for some reason. It was a good time.

Our very first week, on Friday, the editor sheepishly asked us if we’d like to go have a snort. I misunderstood and thought he meant something that he didn’t mean. But whatever, it was my first real job, so I said yes. It turned out he just meant having some whiskey, which was also fine. This is irrelevant, really, I’m just offering some atmospherics on that particular time and place.

Early on in the job, I was charged, along with another intern about my age, with revamping the magazine’s music section. Among our ideas was to get short bits written by musicians or prominent writers about some aspect of Southern music. Something different than music-critic types writing reviews or profiles. I believe the lingo at the time for this sort of brief, design-heavy, blurby mini-section was a “point of entry.” Editors really liked talking about “points of entry.” Heh. To make the concept simple, we settled on the idea of a list. Everyone loves lists! Like a top-ten list with a sentence-or-two blurb for each entry. Not exactly original, but it would have been fun. So the thought was we could have, I dunno, Marty Stuart write about the ten best outfits in country music history or get Cee-Lo to write about the ten best Southern rap songs, stuff like that.

This never quite got off the ground, but this was the plan. I suggested that we get David Berman to do one. I emailed him and explained the concept. There wasn’t any PR go-between or anything like that if I recall. Or if there was, they just sent me his email address.

Berman was in to the idea but he had one condition and he told me this was non-negotiable, that he would absolutely not budge: If we published his piece, we had to also publish his home phone number—with the article or in his bio—and include a small note to one of the Dixie Chicks (as they were then known), letting her know that he wanted to get in touch with her. Shamefully, I now can’t remember which Chick it was. I think maybe he knew her, or maybe even had once gone to school with her? I can’t remember the details. But I’m pretty sure there was some actual connection, this wasn’t just a creepy stranger. In any event, I gather that he had been trying to get in touch with her without success, and this seemed to him a good way to communicate with her. Or maybe he just wanted to have his phone number out there—in case someone wanted to call.

He would only let us publish the piece if we would also publish his number and the note. It was a dealbreaker. I said, without asking anyone, that it should be fine.

Not long thereafter, he submitted his entry. It was very funny, and strange, and whipsmart. Or that’s how I remember it. It’s hard to say for sure. I was 23 years old, prone to juvenile humor, utterly certain of my own aesthetic instincts. I was very good at arguing and usually wrong. So take my judgment with whatever grain of salt you like. But I’m pretty sure it was a weird and perfect little artifact from Berman.

But I’m afraid I can’t even remember what it was about. I do remember that it was a list that was well off kilter of a straight take on the assignment. It was poetic in Berman’s accidental way, a deadpan assembly of facts, lies, and gags. I think. You could say it was roughly in the stylistic range of the reading (poem?) “Top Ten Redneck Moments” that he did for Pitchfork in 2013—or the sort of thing you might find on his blog.

Berman’s submission was a list of about ten, with a blurb for each entry, and its form was something like Ten Best Southern Rock Anthems or Ten Important Moments in Tennessee History, something like that—and then the list did not actually include any anthems or any moments in history at all, it just had little blurbs about this or that with at best an elliptical connection to the topic or to each other. It’s even possible that the form faded and dispensed with the numbered list altogether at a certain point, not sure.

I wish I could tell you more, or share one of the hilarious lines, or one of the sentences with poignant grit, or one of the mystic turns of phrase. But the only thing I remember is that there was one part about how Shel Silverstein was able to enjoy an endless bounty of fellatio in Nashville during the 1970s on account of The Giving Tree. That part stuck with me.

It may have needed some tweaks here and there, but I thought it should clearly go in the magazine, that it was sharp and funny, a hoot. The editor in chief thought otherwise and killed it. Maybe for good reason, maybe for no good reason—that’s one more detail I can’t quite remember.

Then not too long after, the magazine went under for a while, and all our emails vanished. There’s so much stuff from that time I wish I had, but those emails are gone forever.

Data seems so tangible that I find myself wondering where it goes when it goes away. I want to visit the negative server in the digital beyond where all those precious bytes are dead and void.

Whatever David Berman wrote in those emails is gone, his list is gone. All the emails are gone: Joy Williams complaining about my annoying fact checking questions; confusing notes from Swamp Dogg; explanations from Marty Stuart about the particulars of a story he liked to tell about Willie Nelson; and so on. Plus all the little office dramas and life dramas of that particular year and our particular circle in Little Rock. The stuff of mundane history—of interest mostly just to me.

But this is just the nature of things. The volume of information that is saved is massive, and has been steadily getting bigger, a growth that is now probably exponential. But it’s still not as large as the volume of information that’s lost.

Whatever it was, it was the most minor of David Berman ephemera, equivalent perhaps to an unpublished draft of a blog post that no one has thought to miss. Still, I was the keeper of this inconsequential aside—and my memory was faulty, I was relying on the written records, which I thought I was keeping, until they were gone. I didn’t think to back up my emails; I doubt I even knew how.

I do remember that Berman was kind in his notes.

If I had been the editor of the magazine, I would have at least published his phone number as he requested, even if we passed on the piece. Why not?

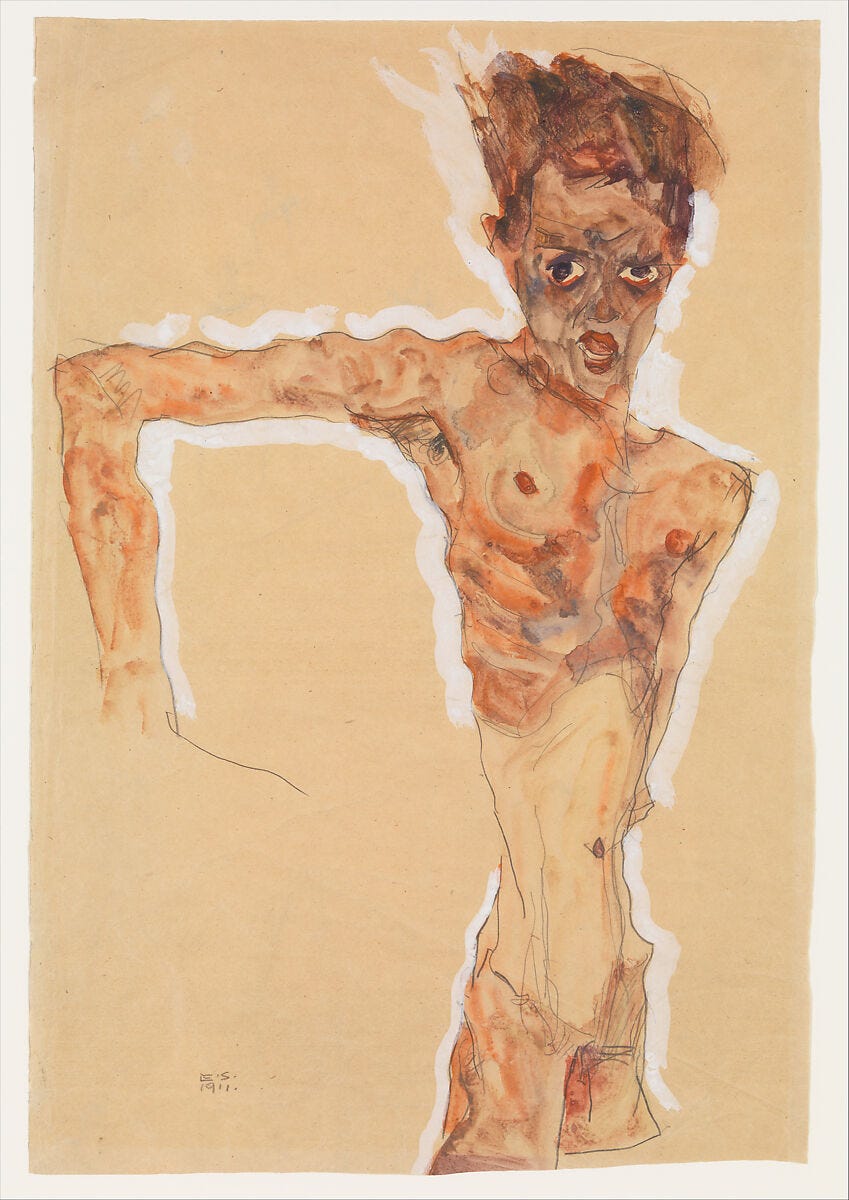

Once upon a time, David Berman wrote a poem called “Self-Portrait at 28.” Maybe he was 28 when he wrote it, but I’m not certain and I’m not going to look it up.

You can read the full poem in its entirety here. I’m not sure about the copyright implications of reprinting the whole thing in this space, but here’s just the opening, part one of five parts:

I know it’s a bad title

but I’m giving it to myself as a gift

on a day nearly canceled by sunlight

when the entire hill is approaching

the ideal of Virginia

brochured with goldenrod and loblolly

and I think “at least I have not woken up

with a bloody knife in my hand”

by then having absently wandered

one hundred yards from the house

while still seated in this chair

with my eyes closed.It is a certain hill.

The one I imagine when I hear the word “hill,”

and if the apocalypse turns out

to be a world-wide nervous breakdown,

if our five billion minds collapse at once,

well I’d call that a surprise ending

and this hill would still be beautiful,

a place I wouldn’t mind dying

alone or with you.I am trying to get at something

and I want to talk very plainly to you

so that we are both comforted by the honesty.You see, there is a window by my desk

I stare out when I’m stuck,

though the outdoors has rarely inspired me to write

and I don’t know why I keep staring at it.My childhood hasn’t made good material either,

mostly being a mulch of white minutes

with a few stand out moments:

popping tar bubbles on the driveway in the summer,

a certain amount of pride at school

everytime they called it “our sun,”

and playing football when the only playwas “go out long” are what stand out now.

If squeezed for more information

I can remember old clock radios

with flipping metal numbers

and an entree called Surf and Turf.As a way of getting in touch with my origins,

every night I set the alarm clock

for the time I was born, so that waking up

becomes a historical reenactmentand the first thing I do

is take a reading of the day

and try to flow with it,

like when you’re riding a mechanical bull

and you strain to learn the pattern quickly

so you don’t inadvertently resist it.

I adored this poem when I was 28. I am not sure whether I adore it now; it honestly feels too hard to know, to experience it as my self, whatever that might mean, at 43. It is too wrapped up in the other self, the one at 28, reading this poem in my 28-year old body, looking out a window in north-central Florida, or wherever I was. Was that self distinct from me? Are those memories, formed by that past self’s present-tense experiences, a kind of phosphorescent string in my consciousness that connects me to myself—to all the selves across the years? Or is it something more like a daisy chain, round and round we go? Or are they just pale predictions of the past? Do I owe anything to my 28-year-old self? Does he owe anything to me? I only know that I feel a great sweetness toward that young fella, I love the way the poem sounds in his head, I love the way he looks out the window. Did I tell you about the time we tried to get David Berman in the Oxford American, says this younger self, and tells the story to someone, better than I’ve told it today because it was fresher and he was funnier. It is his stories that I remember better than the memory itself.

Picture David Berman at every age, at every age he made. He is looking out the window on a day nearly canceled by sunlight. He is singing a song.