This is the tenth edition of Honky-Tonk Weekly, a weekly(ish) column here at the Tropical Depression Substack. You can read previous editions here. Every week, I will listen to and share a country song and write whatever comes to mind. Listen along! This week, we’re getting the heebie jeebies with Johnny Paycheck.

In country music, some songs are defiant, some wallow in abject surrender. Some both.

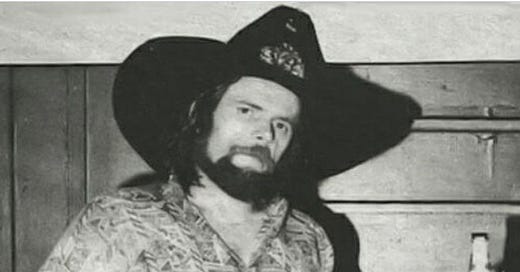

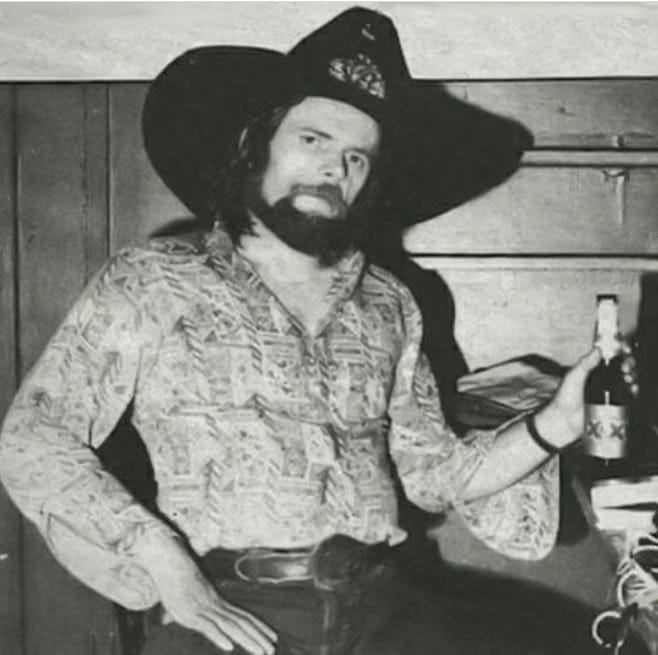

Like Hank Williams before him, Johnny Paycheck was a maudlin emotionalist and a take-no-shit redneck drifter. Hank was skinny as a skeleton and Johnny was about five foot five. But they carried themselves like big trouble. They got very, very drunk, and carried on.

Their terrain was loneliness, which seemed to take on an almost physical form for them. The walls were always closing in. They didn’t mean to be poets, it just turned out that way. Hank would record talking blues as a character named Luke the Drifter, highly emotive little homilies, and move himself to tears. I’m not aware of Johnny Paycheck making himself cry, but I wouldn’t put it past him. Our Outlaws have always been emo.

People who don’t like country music perhaps find this unseemly, all the weeping and wailing. But the notion that popular music ought to be cool and detached is just a passing fancy like any other. If we neglect melodrama, we impoverish the form.

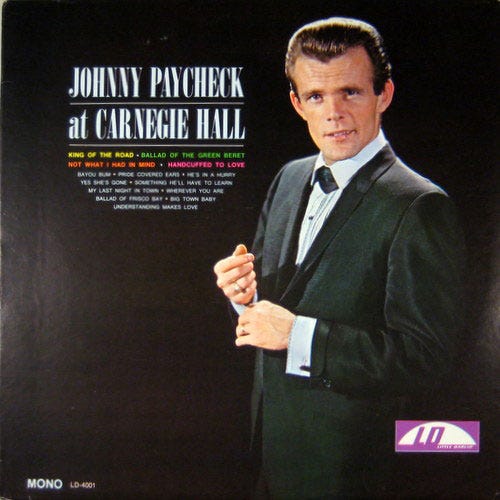

At first it’s hard to square Paycheck’s early squeaky clean early look with the almost cartoonish cowboy rebel sneer he had by the time he got fully famous. But he was always a showman. He played the talent shows when he was nine years old and went on the road to make a living at it when he was fifteen.

Like Hank, though, the bad news was not just an act. Hank spent plenty of nights in jail or the sanitarium but managed to wriggle out of too much legal trouble during his twenty-nine tumultuous years (among the close calls: while trying to shoot his then wife, he accidentally nearly killed June Carter, the bullet whizzing by her head).

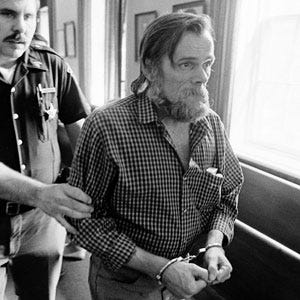

Paycheck wasn’t so lucky. During a stint in the Navy in the 1950s, he got court-martialed for punching a superior officer, and spent two years in prison. Later, in 1985, he shot a man in a bar in Hillsboro, Ohio. He had been planning to visit his mother for Christmas. At this point, he was at the back end of his career, but still a legend. A couple of guys started messing with him, according to his account. One of the men offered to make Paycheck a home-cooked meal of deer meat and turtle soup.

“What do you think I am, a country hick?” Paycheck responded. Then he shot him with a .22, grazing the man’s head. Paycheck eventually wound up spending two years at the Chillicothe Correctional Institute, until the governor of Ohio commuted his sentence. During his sentence, Merle Haggard came to visit and they played together for the prison.

And there were other minor scraps and scrapes with the law—like Hank, too many to catalog in full. Reportedly, once while he was on tour in Canada, Paycheck was arrested for drunken shenanigans at a hotel. He showed up in court the next morning still shirtless from the night before. “Fuck the queen,” he hollered at the Canadians.

Some of the stories are yet more bleak and not at all funny,1 but in general, the mishaps added to the legend. The details always turn out to be very sad if you dig a little. But the truth is, if you’re playing a Black Hat character, it helps if your bio has some venom and vinegar. “Pardon Me (I’ve Got Someone to Kill)” hits different when you’ve done time for nearly killing a man over soup.

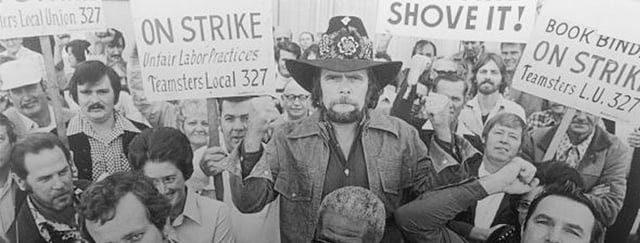

As a singer and musician, Johnny Paycheck was an all-in performer with a chameleon range. The Outlaw turn was likely at least partly a gimmick to sell records, but that’s okay. I am thankful that he brought his own peculiar fire to “Take This Job and Shove It,” the David Allan Coe-penned classic. Or that he hammed it up on “Me and the IRS.” He was a dirt-poor boy hopping the trains as a teenager who earned his GED during an early stint in jail. The aesthetics of Outlaw Country were a theatrical schtick (and occasionally he goes almost too on the nose for my taste), but only a scattering of singers in the history of popular music have brought the intimate fury and comic sneer to working class anthems that were effortless for Paycheck. When he showed up at a miner’s strike in Harlan County, he was greeted as a hero.

But he was also a brilliant practitioner in a more tender mode, as a classic country singer in the mid-60s with a sound that was already becoming a bit retro. This got buried a little in the Outlaw image that came later, but he had a knack for writing by-the-numbers genre songs with nuance and grace. And as a pure singer, especially early in his career, he was an all-time great—an emotive crooner with little surprises in phrasing and cadence that add a richness to his songs. Check him out on “Touch My Heart” from 1967, for example. Or “Not What I Had in Mind,” from the year before. There’s an unconvincing tale that George Jones lifted his singing style from Paycheck, but in any case, Paycheck was in rarified air when it came to the vocal mechanics of the tearjerker.

As an older man with older vocal cords, he brought these instincts to the song he claimed as his favorite, “The Old Violin,” in 1987.2 It’s a morbid ballad seeped in his own despair about aging and death. I really wish they had turned down the very hammy production on the recording, but the song hints at Paycheck’s unique gift: Sometimes our deepest and most meaningful thoughts are corny and overfamiliar. There’s only so many ways to say that it is hard—to grow old, to die. Paycheck does not run from the cliché. He stops and looks and lingers. He wallows. He croons. This is Paycheck: a hokey existentialist. Unapologetically so, relentlessly so. He runs his hand along an old wound—it is not special but it is his.

And the chameleon performer wore more hats still. Paycheck could sell himself as a slick-talking horndog in creeper country that veers nearly into adult contemporary for the late-night radio set; he was just as forceful and convincing singing straight-on country gospel. And while the Nashville Sound isn’t always my first choice, there are gems I dig from Paycheck’s forays into smooth country, as well. His perfectly addictive “She’s All I Got,” his first single after moving to Epic Records and joining up with hitmaker Billy Sherrill, finds a winning groove (the song, co-penned by Swamp Dogg, had been a hit on the pop charts for R&B singer Freddie North; Paycheck’s crossover rendition is a classic of early 1970s country radio). When Paycheck first arrived at Epic, Sherrill recreated his sound in a more pop-oriented direction, with lush arrangements and a radio-friendly sound.3 There are certain songs from this period that I skip, but even when things got quite schmaltzy, Paycheck’s charm often saved the day.

But for me, his best mode was the honky-tonk singer, tears in his beer. Songs with titles like “Meanest Jukebox in Town” or “The Pint of No Return” or “It’s Only a Matter of Wine.” Or “A-11” in 1965—his first single to make the charts, and an absolute classic from the opening line, which lingers like a haunt: “I just came in here from force of habit.”

Or our featured song this week, from 1968, which I find to be Paycheck at his most immersive. “If I’m Gonna Sink” is a groovy song, a boozy lament that does not waver in its register of despair. If I’m gonna sink, might as well go to the bottom. You could maybe put it on the jukebox and dance or you could just sit on the barstool staring into the mirror behind the bar. What a perfect opening couplet: “Well here I sit in this honky-tonk feeling mighty low / Hating to see that old clock on the wall saying it’s time to go.” Oblivion is not poetic, it is just oblivion. Still. It can be seductive, as Johnny Paycheck—and Hank Williams—knew all too well. “When I get the heebie jeebies, this jug’s the only way to stop ’em,” he sings. “If I’m Gonna Sink” explores a very Paycheck sort of pathos: He’s made so many bad choices that he figures he might as well surrender to even worse choices tonight.

These classic honky-tonk numbers were the Paycheck songs that felt the most lived-in. The urgency in his confessions, the totality of his submission, is both catchy and brutal. Or maybe it’s just mimetic of an inebriated state of mind. Getting drunk is a motif in country music because it works as both dumbass corporeal reality and metaphor. We have our life and our sufferings and our redemptions and our regrets and our hopes, and it’s all so small when you think about it, but it feels so expansive and consuming, too, if we’re being honest, and sometimes it is okay, righteous even, to let it all balloon, to take notice of the proper pang of lonesomeness, to admit to yourself that from the only point of view you have, your lonesome consciousness, it is all so hard sometimes and also so exquisite and wonderful sometimes—that your life, like every life, can only be rendered in cornball emoting, can only be reckoned in melodrama. If we’re being honest, I mean. This expansive frame of mind is perhaps best primed in the confines of a particular sort of bar, but it need not be. Teetotalers, too, are prone to every manner of the blues. If you’re gonna sink, you might as well go to the bottom.

In 1981, he was arrested for the alleged statutory rape of a twelve-year-old girl in Wyoming. He ultimately pleaded down to a misdemeanor and received a $1,000 fine. He cited other legal difficulties and a tax lien at the time as making it complicated and expensive to fight the charges in Wyoming, as well as a desire to shield his family from the publicity of a trial. From police statements at the time, it seems that the charges did not allege physical force—though of course given her age, legal consent was impossible. I’m not sure if he admitted having sexual intercourse with the girl or if he otherwise made any additional public comment.

The song is from Modern Times, an album that has never been reissued, but you can hear that record in full on YouTube; here’s the re-recorded version of the song he released in 1993, which takes an already over-the-top song further over the top still.

Sherrill is known for lovey-dovey crossover music, but ultimately his real interest was selling volume any way he could; he was still around when Paycheck went full Outlaw.