How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!

On Cash & Coe

When Johnny Cash died in 2003, I heard the news in a bar in Little Rock. You could still smoke then, and the bar was filled with smoke. The woman I was with cried. This seemed to me a righteous reaction.

I heard a story that at the end of Cash’s life, Merle Haggard was trying to visit him in the hospital but they wouldn’t let him in the ICU. In the version I heard, someone in the family dressed him up in hospital scrubs and snuck him in. Or in Merle’s telling, when they turned him away, he snuck off and grabbed a doctor’s white coat straight out of a closet in the hospital and no one was the wiser when he walked on in to say goodbye. I like the image of the scrubs best, so let’s go with that. I’d like to think there was an uncanny moment for the dying man as the diminutive figure approached: A nurse? An old friend? A strange angel?

It was almost twenty years ago that Cash died. Can that be true? He was a man, just a man, and God is no respecter of persons. Still. By my lights, it is hard to reckon that he was a mere person, with a human body and a brief plot in our human story. For me, he remains one of those performers unmoored from the notion that the source of his art was a human mind made up of the same stuff as mine. In a pissing, farting body with an expiration date. I cannot shake the feeling that instead he was a channel to those visions behind the dim mirror. For me, he was like Moses.

It hardly matters that the myth of Cash, like any myth, was manufactured; that he could be hokey does not break the spell. There’s no business like show business.

Here’s Tony Tost from his 2011 book on Cash:

Johnny Cash introduced one great character to the field: the mythic version of himself. It’s the Cash we like to prop up as the authentic one, the evil old sanctified soothsayer that Kris Kristofferson called a biblical character, “some old preacher, one of those dangerous old wild ones,” a final prophet in a slow fervor at his pulpit. Pistol in one hand, a page of Revelation in the other? Taste of blood rising in his throat? Sort of a stock character by now, one foot on a ladder to paradise, the other on some shitsucker’s corpse. This version of the man, being made of myth, answers to a list of names: usually to Cash, sometimes to the Man in Black, rarely to John, never to JR, now and then to Sue.

I do not mind being hooked by a myth, not at all. Sometimes I admire art, or a song, or a book. And I can describe, in the language if not the expertise of a critic, why that is so. But then other times, there is a kind of mythic force. Maybe you will know what I mean. A piece of art that cannot be properly described in the language of the critic at all, but requires something more like the language of the low-church preacher. For example: The songs of Johnny Cash, sung in the voice of Johnny Cash, filtered through the story of Johnny Cash, sung by the character of Johnny Cash. When I listen to these songs, it is not just that I am reacting to the songs themselves. They seem pulled from somewhere, and they pull something from me. Or they conjure, or awaken, something within me. Something normally concealed. Within my body, or my mind, it’s hard to place. An indwelling of the spirit, let’s say. Or the Spirit, if you like.

A little more than a decade after he died, a “lost” Johnny Cash album was released. The recordings were made during sessions in 1981 and 1984 for Columbia Records, but never released. This was during a downturn in Cash’s career. In 1981, he got hooked on painkillers again after being kicked by an ostrich. But some of these recordings, finally released in 2014 as Out Among the Stars, were pretty solid—far from his peak but certainly a worthy entry in the catalog.

Like my parents, John and June Carter Cash were apparently dogged archivists of their own life stories. “They never threw anything away,” their son John Carter Cash told the media when the recordings were finally released. “They kept everything in their lives. They had an archive that had everything in it from the original audio tapes form ‘The Johnny Cash Show’ to random things like a camel saddle, a gift from the prince of Saudi Arabia.”

I feel thankful that they kept the recordings. And the Arabian saddle, too. I’m not sure I agree with John Carter Cash about what counts as random.

It felt like something of an event when “She Used to Love Me a Lot,” the first single from these sessions, was released in early 2014. The song tells the story of a man who sees an ex-lover at the Silver Spoon cafe and hopes to rekindle the flames—a cozy, tear-in-my-beer ballad that sounds like classic Cash.

Short of a masterpiece, but at least a relic: No word from the tablets, but perhaps a strip of the prophet’s garment.

It helped that the recording was thirty years old when it finally saw the light of day.1 As far as I can tell, it was the contingent vagaries of Columbia’s business office and contentious relationship with their star that kept the tracks buried, not quality control (Cash was unceremoniously dumped from the label in 1986). Unlike most posthumous recordings (Cash’s included), “She Used to Love Me a Lot” felt like a genuine song from the irretrievable past instead of the standard filler of that liminal space between the death of a star and the bottomless market demand for a perpetual catalog machine.

Really, it is hard to figure how this song got buried in the early 1980s (especially since Cash released no shortage of duds in his prolific recording career). Years later, the market could not get enough of this brand of Johnny Cash, but at the time I suppose it felt dated? Doing publicity for the belated release in 2014, John Carter Cash’s diagnosis was that Nashville was fixated on the Urban Cowboy vibe in the early 1980s and no one quite knew what to do with the Man in Black. Maybe even Cash himself didn’t know: Part of the reason that “She Used to Love Me a Lot” felt like a gift is that his output during that period was quite spotty. Like the unfortunate 1984 single “The Chicken in Black.” Reportedly wounded by Waylon Jennings telling him he looked like a buffoon, Cash had the music video pulled…you really have to watch it the whole way through, it’s hard to believe it exists.

When I heard “She Used to Love Me a Lot,” there was something immediately familiar. Cash relentlessly revisited his sonic hobbyhorses, so déjà vu is no surprise. And of course that voice is always familiar, like wriggling your toes in your old home turf. The song falls so naturally into the cadence of Cash. But then I realized I’d listened to this tale of the Silver Spoon cafe before. Penned by Music Row hitmakers, David Allan Coe took the song to #11 on the country charts in 1984, the same year that Cash recorded his take.

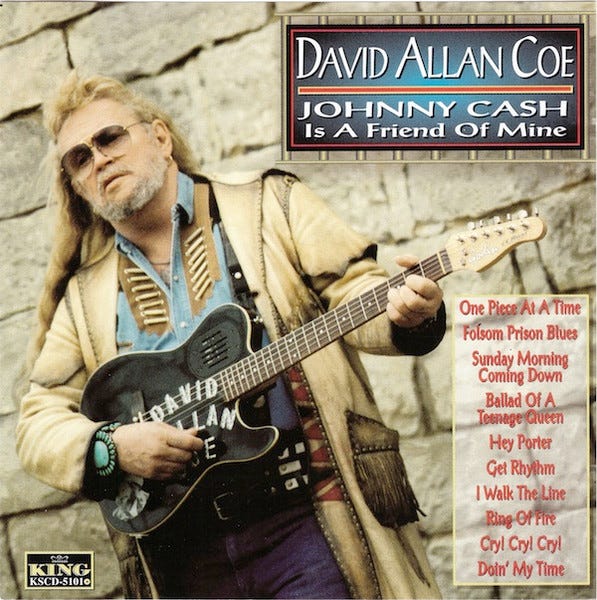

Here is another mythic force from country music: David Allan Coe, the grisly, grotesque Outlaw, who once supposedly fled the IRS and went to live in a cave in Tennessee. As a young man he wrote one of the most beautiful songs in the country music pantheon. He kept writing beautiful songs and all-time scorchers along and along, year after year, even as he had his own unlovely patch, descending at times into a sordid and bloated cartoon, infatuated with Confederate flags and risqué racial lyrics and tedious provocations. Some of it is indefensible. Our ancient myth, the fallen angel.

But God help me, I can’t quit Coe. The Opry’s ethos, which lingers in Nashville still, established a popular music for the sort of people who score as highly conscientious on the personality tests. But there is this other thing.

Just like Cash, Coe conjured the mythic version of himself. The cuss, the scoundrel, the moaning devil. His natural vernacular was not the King James meter but the drunken certainty of violent quarrel on Daytona Beach.

All satisfied people are alike; each desperate man is desperate in his own way. Coe was a voodoo redneck. He grew old and his dreadlocks grew long. Ain’t that America?

In 1882, the bloody family feud between the Turners and the Howards began in Harlan County, Kentucky, when Wicks Howard shot Little Bob Turner over a card game. (Or because he spoke ill of his mother or because of a dispute over a dog—accounts vary; “I don’t remember what the disagreement was, but they killed him,” one Turner remembered later.) “The county is wild, and the whistle of the locomotive has never been heard by many of its inhabitants,” reported the New York Times in 1889, putting the body count at somewhere between twenty-five and fifty. Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky describes one skirmish, when Will Turner—Little Bob’s brother—tried to rush the front door of the county courthouse, where armed members of the Howards were firing:

He was hit before he reached it, got up and retreated, firing as he went, but was hit again. He got up and, with the help of others, staggered up the street to the Turner home, where his mother came out and helped him onto the front porch. He had been hit in the stomach and was screaming with pain. “Stop that!” his mother snapped. “Die like a man, like your brother did!” Will stopped screaming and died.

This story just ruins me. Later, when a mama from the Howard side tried to forge a truce with Will Turner’s mama, she declined, pointing to the spot on the porch where Will had fallen. “You can't wipe out that blood,” she said.

I’d love to listen to Cash sing a song about that, but I think I’d want Coe to write it.

Back to “She Used to Love Me a Lot.” Both the Cash and Coe versions are great, give them a listen. This was long before Coe was in full bloom as a cartoon caricature of himself, and long before Cash had been fully canonized as an icon above reproach. Still, their personas feel more or less fully formed in these interpretations.

Where Cash is mournful, Coe is sleazy. Cash: “I remember how good it was back then.” Coe, in a slithering whisper: “I reminded her how good it was back then.” Coe, that dirty dog.

“It’s not too late to start again” from Cash is a lament—a knowingly false hope. The same line from Coe sounds as much like a menacing threat as a come-on.

Cash is sitting alone in the corner. Coe is hitting on drunk women. A proper honky-tonk has both characters.

When an interviewer asked Coe in 2003 why he and Johnny Cash were such good friends, Coe said, “I think John was attracted to me because I'd been in prison so long.” Kind of a funny thing to say. But Cash knew a good myth when he saw one. Here was a character: A raunchy biker who went from the Ohio penitentiary to living in a red hearse parked outside the Grand Ole Opry just hoping someone would notice him. He went around telling people that he taught Charles Manson how to play guitar. When he made it big, he owned seven Cadillacs. Also two jaguars (cats not cars), two leopards, and a bobcat. Penn and Teller (Coe was very into magic, by the way) saw him play in the 1970s and this is how Penn Jillette described the scene:

He did not like the audience. He said, “Fuck you. All you deserve is the Eagles.” He then had the whole band play the Eagles for half an hour, while the audience threw beer bottles at them and screamed.

Coe had these strokes of genius, but there is no mystic aura: He is just a man, in a pissing, farting body with an expiration date.

In 1985, Coe was having a nervous breakdown, according to this account in GQ. Johnny Cash had people over for Thanksgiving dinner. Willie is there, Kris is there, etc. Coe is in a bedroom upstairs, in a bad way. Cash walks up the stairs carrying a baby, around one year old. He hands Coe the baby and tells him to look after the child for a second. The baby is Coe’s son, who he has never laid eyes on before. Later the boy will join Coe’s band. Later still, he will become estranged from his father. Tyler Mahan Coe told GQ that to be angry with his dad “almost feels like being mad at a dog. Of course he shit on your floor.”

In the cinematic universe of country music, if you meet a prophet on the road, there is likely a carnival nearby. Be cautious of demons. Sometimes I fear the brimstone. But sometimes, in spite of myself, I want to get all the way down in the mud.

For some (or all?) of the songs on Out Among the Stars, the archived masters were “fortified” in 2013 by a team of musicians including Marty Stuart.