This is the twelfth edition of Honky-Tonk Weekly, a weekly(ish) column here at the Tropical Depression Substack. You can read previous editions here. Every week, I will listen to and share a country song and write whatever comes to mind. Listen along! This week, we’re remembering the country side of Tina Turner.

It was just so unlike me, my life.

—Tina Turner

She worried that she had a short neck and a short torso. She was afraid of spiders and snakes. She was always attracted to myths. She believed in the cosmic energy of every man and woman. She hoped that astrology could help her find the hum of the soul.

She spent nearly the last three decades of her life in Switzerland. She learned to speak a little conversational German but never learned to yodel. Her favorite season there was the fall. “With the fall,” she said, “the quietude starts.”

There are so many stories and nuances and layers about Tina Turner, born Anna Mae Bullock of Nutbush, Tennessee, and there have been no shortage of tributes to read in the last six weeks—none of them quite capturing it all but many of them at least trying to honor her in her totality, which you cannot do, but you perhaps feel compelled to try, because her influence and her oomph seem so total, like a current of electricity charging the last sixty-five years of popular culture.

Let’s try to simplify. Let’s pick just one thing: her voice.

And see, already I feel guilty about omissions. Isn’t there a case, just for starters, that she was one of the most influential dancers of the twentieth century? And can we reckon her voice, in any meaningful sense, in isolation from the way she moved?

Well, let’s try.

In the early days, the journalists always made a note that she was tiny—perhaps in part a way to describe the shock of the bombastic sound she made when she let it rip. “One of the most dramatic and unusual voices in show business,” a Cleveland newspaper wrote in 1964. She always sounded a little hoarse, with the high drama of gospel and the boogie-woogie perspiration of a honky-tonk angel. It was overwhelming, but hard to place: She was downhome and divine, like a Siren just getting over a cold.

“I can’t remember that I ever didn’t sing,” she once told an interviewer. She was the lead singer of her church choir as a child. “In Nashville, where my parents lived during the war, the seller from the store sometimes gave me some money when I sang. I collected them all in a nice box of glass. It was as if even then I knew that I would earn my money with singing.”

She grew up Baptist, but she had a very different style than the Black Baptist singers popular in the first half of the twentieth century, a starting point for proto-soul singers who would cross over into pop and R&B by the 1950s (like Sam Cooke, an early idol of Tina’s). Jubilee quartets and their cultural descendants1 wore dapper clothes and sang with the restraint and artistry of tight gospel harmony. Their movement was disciplined and understated. Their holiness was expressed by their manners.

Tina’s style was something closer to the Holy Rollers of the Pentecostal church, who had a wild and populist understanding of religious experience. The Holy Spirit was available to anyone willing to receive it, a kind of all-consuming connection with the divine that was loud, raucous, uncouth, physical—a furious, rhythmic spiritual transformation not of this world, not legible in material terms. If this wildness looked weird to others, that was just as it was written: Didn’t Paul explain to the Corinthians that the things of the Spirit would appear as foolishness to those grounded in the material world?

I’m not certain, but you have to guess that Tina was exposed to the Church of God in Christ growing up in West Tennessee, even if her upbringing was Baptist. But by the time she got to the St. Louis area, it hardly would have mattered, as the ecstatic style had already thoroughly seeped into the burgeoning mass media culture. You didn’t have to go to church, you could just put a coin in the jukebox. Sister Rosetta Tharpe had started making noise on the R&B charts in the late 40s; white Pentecostals like Elvis and Jerry Lee had brought the flavor of revival meetings to megastardom on the pop charts; Little Richard was reinventing the very possibilities of a popular song.

Elvis was not the only one—just the most famous—who noticed that the way the Spirit moves the body of the faithful was a medicine that the not-always-faithful could channel for more lurid ends. This was a paradox Martin Luther might have gotten a kick out of but would torment Jerry Lee Lewis; in any case, it caught on.

And then there was Ike Turner, who also had a Baptist upbringing, but had preternatural instincts for this new sonic territory in pop music.

Ike’s blues chops were not so different than St. Louis contemporaries like Oliver Sain or Little Milton—who like him had rural Delta roots but had settled up north. Those guys had picked up modern rhythms and cosmopolitan vibes in the city, too. The difference was that Ike’s impulse toward shake and noise and raunch and boogie just hit him harder, somehow. Ike was country, but his ear was burning with the new. Like: Listen to this, from all the way back in 1951. Rock & roll has no singular architect, no singular birth, no one prime mover. It happened slowly and all at once, among lots of different people in lots of different places. But I am comfortable saying that one of those places was East St. Louis, Ike Turner with guitar in hand at Ned Love’s place, say, making them swoon with his focus and his fury. One thing though. Maybe he knew it or maybe he didn’t—or maybe he always knew but he could never, ever be happy about it: To really go where he wanted to go, he needed a voice to match that heat.

When she was still in high school, Tina would go with her sister across the river to the nightclubs. Everyone said the same thing: East St. Louis was wide open. When Tina saw Ike on stage the first time, at the Manhattan Club, she was seventeen. “I almost went into a trance when I saw him,” she said. Lots of stuff happened after that.

I want to say that Tina’s voice is leathery, but that word has managed to become a cliché without really conveying information with any sort of precision.

I think what made her sound so compelling is that she had undeniable pipes, but there was a kind of natural strain in her execution. Her sounds had a palpable texture, frayed at the edges. She could reach operatic heights but was a throaty, almost guttural performer, bending the melody to make room for raggedy and weathered undertones. Her notes could break or crack without ever undercutting the strength and force of her voice. She sang loud and proud, but something in her phrasing was marked by fragility. I don’t know of another singer that could convey such indefatigable fire and bluesy exhaustion at the same time.

The way even a familiar old song sounded when you handed her the microphone: It was arresting and discombobulating and emotionally explosive. It was physical. And very, very fun. A critic in 1969 complained, “Tina’s earlier hits focused on her ability to sustain and modulate a scream into a singing style, a style which was exciting but too wearing for prolonged listening.” They almost got it.

Her peculiarities in sound and affect were magic ingredients for that particular moment. Rock & roll was a sonic grab bag still sorting out an identity. Tina had the voice for the new sound—you could argue that her style of singing was a defining archetype, or at the very least a bedazzled perfect fit—because she was a joyful and groovy singer with another gear, on the edge of terror. Rock & roll could make you dance and it could also make you scream.

There’s another thing, too. To my ears, the electric quality to her voice is deeply androgynous. Tina’s performance was smoky and sexy, with a particular sort of male charisma and motherly confidence and femme glamor. “I never…wanted to be real feminine, you know like the girl singers,” Tina told Dick Cavett in 1972. “Because you know, when I started singing, Ike had mostly male singers, and I wanted to sound like they sound.” Her early models were men like Ray Charles; she never really had a lot of female influences, she said.

Someone smarter than me could maybe write an essay about androgyny as one of rock & roll’s secret ingredients. There was a kind of autoerotic circularity in the gender-bending channels of influence: Rod Stewart and Mick Jagger wanted to be Tina Turner; Tina wanted to be Rod or Mick (worth noting that when Tina was cast as the Acid Queen in the film version of the Who’s Tommy, David Bowie had been the original choice for the part). Rock & roll was transgressive, charged, unfixed, fused in fusion. Women who sing a little bit like men and men who sing a little bit like women—these would be rock’s avatars, befitting this tricksy new form.

There is a temptation to explain Tina’s vocal gifts via biography—to imagine that her emotive range came from the emotive range of her experiences. Artists find ways to channel their pain, but I tend to think that sort of interpretation is overdetermined. Lots of very sad people sound happy when they sing; lots of very happy people can sing in a way that makes you cry. We are hearing her vocal cords vibrate in her larynx as the air rushes in from her lungs. They sound the way they do through accidents of biology, subtle variations, habits of culture and upbringing, performative affect. The stories we ascribe to those sounds are our own.

But those stories sold. Even if it’s a category error to say that the particular qualities of her singing voice were channeling the hard times she came from, this was the mythos that grounded what was coming as rock & roll went mainstream.

As it happens, these qualities in her voice did suit the complexities of her life—beaten down but unbowed. But that’s almost beside the point. A flash and shimmy emerging from hard times: This was the wicked truth that early rock & roll was seeking (or conjuring up). This stuff was marketable. Ike knew that, Tina knew that. Tastes were changing, slowly and all at once. The transgressive edge was leaving the confines of the juke joint. British boys like Mick and Keith were in search of authenticity, of a raw sound that came from unvarnished living, and they surely thought they could discern that in the sound of Tina Turner making well-worn songs her own. The refinement of empire was exhausted and boring; they had a hard-on (literally, perhaps) for the Other. The producer Jim Dickinson, who had his own small claim as a rock & roll pioneer, once put it more brutally: “smart-ass white boys from the suburbs ripping off Black music. That’s rock & roll.”

You could say that there was an almost obscene misunderstanding supercharging all of this. Early rock & roll, like country music, was so rooted in medicine show hucksterism and showmanship that any hunt for authenticity was a fool’s errand. But at a certain point, none of that matters. Of course it’s a performance and a projection, but you forget all of that, if you dig it, because you are overtaken. Ike Turner was three chords and Tina Turner was the truth.

Look what I have done in this lifetime with this body. I’m a girl from a cotton field.

—Tina Turner

Country music was a footnote in the career of Tina Turner and Tina Turner was a footnote in the history of country music. But the novelty of it is one way, perhaps, to hear her fresh.

She was very good when she went country, because she could do anything. It was in part this malleability, her ease across the forms and folkways of American popular song, that made her such a star for the burgeoning genre of rock & roll. One reason rock was so exciting—and had such universalizing, ubiquitous potential—was its ability to absorb everything: country, blues, soul, R&B, gospel. At least some of the plantation singers Ike would have heard in the Delta or the street musicians Tina might have come across in Brownsville would have had hillbilly numbers in their repertoire alongside their blues. Tina’s force of melodrama, and some portion of the driving shuffle that Ike could slide into, had a countryfied energy. Rock was catholic; you had to have a little bit of everything.

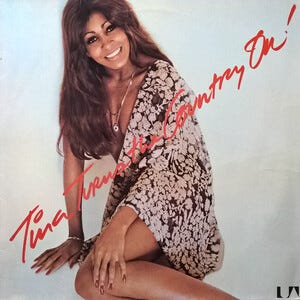

When Tina released her first studio album as a solo artist in 1974, Tina Turns the Country On, she took things in a pretty country direction, kind of a soulful spin on Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Tina herself often noted that she grew up on country and western music, which is most of what she heard on the radio as a kid—and despite her solo debut not selling well, she was fond of the album according to one of her memoirs.

It was recorded in Ike’s studio, Bolic Sound. I suspect he must have been involved, but he apparently didn’t play on the record and he’s not listed in the liner notes at all. Nashville producer Tom Thacker was behind the glass, with session musicians including rockabilly legend James Burton on guitar, Glen Hardin on piano, and other go-to players from early rock and crossover country. Most accounts say that Ike is the one who chose the album’s direction—the Pointer Sisters were showing up on both the country and pop charts with “Fairytale” when Tina Turns the Country On came out, so it wouldn’t have been crazy for them to aim for crossover appeal. I’ve also come across other accounts suggesting that Ike wasn’t around the studio at all for the recording and had nothing to do with how it turned out. Hard to know, but Ike was such a control freak on all things related to Tina’s career that I imagine he must have had some input.

The hokey double entendre in the album’s title was par for the course for Black artists trying to make inroads into country. You could never be too on the nose in trying to assure audiences that country music was on offer even if the face on the cover looked different than what they might have come to expect in the country section (Linda Martell’s debut was called Color Me Country; former Honky-Tonk Weekly favorite Stoney Edwards opened with A Country Singer; O.B. McClinton went with O.B. McClinton Country; Charley Pride began with Country Charley Pride—the story goes that Pride was heard by country audiences before any publicity photo was distributed).

Unfortunately Tina Turns the Country On has never been reissued, although many of the songs turn up on the many knockoff budget CDs collecting Tina’s forays into country music, alongside otherwise unreleased country material recorded at Bolic Sound. It’s hard to figure out why. It was her debut album! Maybe the stuff that came out around that time felt tainted because of Ike? But there’s certainly interest, both for Tina fans and for music fans curious about the country side of Tina. Those budget CDs kept popping up, and copies of the vinyl record now seem to go for $100 or more.

And it’s not just a novelty or relic. It’s great! (at least based on the version on YouTube, albeit with not great sound quality). I will sound like a dumbass music critic if I say it’s a lost classic but…it kind of is?

Despite the title, some clear country elements, and recent media interest in Tina as a coulda-been-country-icon, it overstates the case a bit to call this a country album. The one original, the killer opening track “Bayou Song,” is a bluesy Louisiana rocker with a swamp pop feel and Tina channeling Leon Russell or John Fogerty. The rest are nine covers that kind of run the gamut of late 60s-early 70s folk, easy listening, and country. Three of those were written by country artists; a fourth was a crossover hit for Olivia Newton-John; a fifth was a pop hit for Linda Ronstadt that would have been at home on the country charts. In Tina’s interpretation, the easy listening gets a harder edge. The overall result is more or less Southern soul, very Tina, groovy and cinematic. It would have felt just a bit retro even at the time, I think. Maybe a soundtrack for a Roger Corman film? It didn’t sound like country radio, but it would have fit snugly in a juke joint in the country, white or black. There’s a couple of misses—and the whole thing has a noodling, slapped-together feel—but I dig it.

Tina’s mastery of melodrama leads to a number of standout gems. There’s a sultry cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make it Through the Night” that works, somehow—Tina can turn a country song into soul by the sheer luscious desire in her delivery. A few critics at the time found her style too “tempestuous” for covering Bob Dylan; I disagree—her rendition of “Tonight I’ll be Staying Here With You” finds a gritty pathos that made me hear the song new. If you’re going to do it, best to overdo it. (Her cover of “Long, Long Time,” by contrast, is solid, but Linda Ronstadt’s version was already so full-tilt that Tina almost sounds too subdued.)

Dolly Parton’s “There’ll Always Be Music” gets a Nashville Sound treatment here. The schmaltz is ultimately too thick for my tastes, but for Tina completists, it’s a showcase for her gifts as the song crescendos: blending elements of country, rock, and the Black church, she sounds like she could be captivating a stadium crowd of rednecks with lighters in the air. This is the sweaty exaltation that John Fogerty or Robbie Robertson or even Ronnie Van Zandt were reaching for, Tina is just more.

If you’ll allow me a brief digression on Tina and the Southern rock style: Fogerty was a longtime admirer of Tina’s, well before she covered “Proud Mary.” In his memoir, he recalled that during the time when Janis Joplin and Grace Slick were beloved in the 1960s underground scene, “I just thought, ‘Man, Tina could sing circles around them. (Or Mavis Staples!).” John Fogerty grew up in the Bay Area, where his father operated the typesetting system for the Berkeley Gazette. Young John had good taste in music, and he started playing in a cover band. Turns out he had a marvelous imagination and he was a good mimic. Nothing wrong with that. When Tina and Ike covered Fogerty’s “Proud Mary” in 1971, it became the defining hit of their career. Another tale for the circularity of influence in rock & roll, as Fogerty recognized: “It felt like a really positive thing, that sense of paying back and honoring your influences.” Fogerty was not from the South, but he wrote a perfect Southern song—and perfect, it turns out, for musicians he loved and covered back when he was a teenager: Ike and Tina.

Tina’s version opens with a lascivious spoken word intro, a kind of mission statement for the music of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue: “we never do anything nice and easy—we always do it nice, and rough.” The song starts with a warm, swaying lull before the tempo suddenly bursts into a frenzy a couple minutes in and Tina’s vocals explode. It makes me think of a line from a quickie review note I found in Billboard of Ike and Tina’s very first single, “A Fool in Love,” back in 1960: “a touch of gospel style in the screaming passages.” The Creedence Clearwater Revival original is an absolute classic, of course, but as the writer Jason Heller put it, “Turner upped the intensity of Fogerty’s country-rock anthem by a factor of 10…it’s Turner’s soulful ecstasy that sells it.”

Tina is and always was a deeply Southern performer. That’s not the same thing as country, of course, even if they can get conflated by people who mostly associate country music with the second person plural and regional vowels. You can hear it on her first singles, you can hear it on “Proud Mary,” and you can hear it on Tina Turns the Country On. “As always,” one reviewer of Tina Turns the Country On wrote, “Tina’s voice is a liberal helping of grits laced with honey.” If we’re going that purple, I might have said grits and gravel—but you get the idea.

The album’s vibe was maybe too unplaceable to make noise at the time and sales were meager, although it did lead to a Grammy nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance. Here in full is the review that appeared in Billboard:

Fine mix of country, folky and soft rock tunes done in Tina's inimitable style. On this effort she flexes her voice from its softest to its usual rough tone and molds it perfectly around each cut. Drawing from a wide range of composers from Dylan to Dolly Parton to Kris Kristofferson to Hank Snow. Ms. Turner should gain easy soul and pop play and possibly some country play. Surprisingly effective are the slow cuts, and Tina proves just as adept an interpreter of other's material as she is a singer of original songs.

There has been an understandable tendency in more recent evaluations to view this as a missed opportunity. “How Tina Turner’s interrupted country legacy could have changed the genre” read a headline in the Tennessean after her passing, which mentions Billboard hedging on the idea of the album getting play on country radio. “In another life, Tina Turner could’ve been one of the greatest country music artists ever,” that story opens. That sentence, I have to say, perfectly captures the provincialism and self regard of my hometown of Nashville. Tina was an international superstar and one of the great popular music icons of the century! Somehow I doubt she was pining for what might have been on the Opry.

Country radio was stiff and conservative, and the industry could be ugly on matters of race, but there was no conspiracy to keep Tina off the country airwaves. That very same year, the Pointer Sisters had at least moderate success on the country charts by using their chameleon talents to pull off a song that fit snugly within the genre’s boundaries. For me, what stands out about Tina Turns the Country On is less Tina as a country singer than the stunning way Tina could make a country song undeniably her own.

Take her cover of Hank Snow’s “I’m Moving On.” Snow is an all-timer and “I’m Moving On” is a great country song with plenty of verve, but it’s also about as square as it gets. Tina retains its twangy spirit but transforms the number into a filthy country-rock shaker. Here’s the song with the most Ike sound on this Ikeless album; she sounds like she’s tearing up the stage in East St. Louis. She sounds a little like Aretha, a little like Jerry Lee, and a lot like Tina.

But what about the Tennessean’s claim, silly as it may be: Could Tina have been a country star? Not that it matters, but I think the answer is yes. Part of what’s delightful about exploring this side of the catalog is spotting the little country flourishes she could weave in—and when she wanted to go deeper than a flourish, she had the country chops to do it. The emotive defiance on display has a touch of Loretta Lynn. She would always be a rocker—her every instinct as a performer pulled in that direction—but there was room for that in Nashville in the 1970s. She could bend the note for high drama and belt out a climax; that “soulful ecstasy” when she sang “Proud Mary” could have served a country diva, too.

A number of country songs were recorded at Bolic that never made it on an official studio album (though they would eventually show up on those budget CDs), including a fantastic version of Loretta Lynn’s “You Ain’t Woman Enough” that sounds closer to Sgt. Pepper’s-era Beatles than to country; a lovely straight-ahead cover of Waylon Jennings’ “We Had it All”; and her rollicking take on “Good Hearted Woman,” which pulls off an outstanding country-Tina blend (Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson were originally inspired to write that song based on ad copy Waylon saw promoting Tina as a “good hearted woman loving two-timing men” in 1969).

But if you want to imagine Tina in an alternate universe as a country singer, take a listen to this week’s Honky-Tonk Weekly song, her cover of Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man,” which I think is probably the most capital-c Country song in her catalog. I don’t have many details about the recording, but it took place at Bolic around the same time as the other country-ish recordings, presumably during the sessions for Tina Takes the Country On (it likewise only saw the light of day much later on the budget compilation CDs).

On some level it’s a showcase for one of the few singers who could match Tammy’s power and spark. But Tina’s take is moodier where Tammy went anthemic—there’s an almost boozy resignation to her delivery. Like George Jones, Tina has a knack for subtle changes in phrasing and little deviations in pace that create new layers of emotion—or perhaps in irony—in the song. A good country song might tell you about regrets; a great country song feels seeped in regret without ever mentioning it in the words. Like any cover of such a well known song, there is an uncanny quality that can be almost distracting. But there is something so rich and warm about the delivery that I can sink into it. It pops.

Be that as it may, it is hard to hear this song, out of any song, sung by Tina and not feel gutted by lyrics. A question hangs over it: Was it Tina’s choice to sing it? A producer’s? Or was it Ike? Was this another subtle provocation? Another casual assertion of control? Was the pathos here as sinister as a first listen to a song like this at that time in her life would suggest? Or is there something sneakily rebellious in Tina’s rendition? Or: Am I reading too much in to it altogether? Was it just another hit country song that she sang at Bolic, hoping for a hit of her own?

Basically from the moment Tammy Wynette came out with the song, there have been attempts to seek a feminist undercurrent in the song’s most memorable line: “After all he’s just a man.” Any listener can hang on to any moment in a song, but at least in terms of Tammy’s version, this feels like a strained reading. The song’s co-writer and producer, Billy Sherrill, was clearly going for a reactionary message. Likewise, Tammy had a starkly traditional perspective and had no problem playing queen of the counter-counter culture. The Silent Majority bought records, too.

I would argue that there is a message of female power in that line, and one could think of it as a form of feminism, though the women it describes would hate the term. It’s just a message that, for better or worse, embraces the patriarchy rather than seeking to dismantle it. Often in families or communities that subscribe to more traditional gender roles, women take pride in exerting power and control in the domestic sphere. This is at least the pattern I’ve seen among my in-laws (or some of my own relatives from a couple generations back) or when I’ve reported in traditional communities. Poking fun at the hapless man in such circumstances isn’t about undoing the patriarchy; it is a way of centering the vital importance of women and the way they hold families and communities together. It’s a way of honoring the patience and endurance that requires, both a joke and a point of pride among sisters.

That’s my take on Tammy’s version, anyway. What about Tina? Standing by her man was the most catastrophic fact of her life for sixteen years. The stakes here weren’t putting up with Ike’s carousing (though he did that, too). He sexually and physically tortured her. He punched her in the nose so many times, she said that blood would seep down in her throat when she sang. She covered up black eyes with stage makeup. He broke her jaw. He scalded her face with hot coffee. He beat her with a shoe stretcher, with a coat hanger, with a belt, with his bare hands. Her life, she said, was death.

Picture Tina Turner in the studio that Ike built singing this song, perhaps a song he picked for her. She is almost, as ever, screaming as she sings: “stand by your man.” That sounds like a scene from a horror movie. But then the tape stops, play it back, and there it is: She slayed it. The emotional pitch—the honky-tonk veneer of regret that she seems to conjure out of the blue from Tammy’s hit—might make us wonder if it was actually Tina who picked this song, if there is a gnarly irony and a gallows humor at play. Maybe, maybe not. We are biased toward belated happy endings. I don’t think there’s a secret message in this performance, but if you want to find one, I’d return to her voice. Those little tricks. Despite singing at such full throttle, she had remarkable command. It’s what made her songs so rich, I think: She could sneak emotional U-turns into a note, like speaking in code. If you find yourself with goosebumps when you hear her sing, it’s not the backstory or the comeback or the movies, moving as they are. It’s her voice.

Sometimes it’s hard to be a woman. I looked around to to see if I could find any old interviews about what Tina thought of recording this particular song but came up empty. So I don’t know. All I know is what got taped—what we can find on those budget Tina country CDs, or now on Spotify—what I am listening to as I type this, and what you are listening to, if you like, while you read.

And then. It would have been a matter of months after the cover of “Stand By Your Man” was recorded: Ike and Tina were in Dallas, planning to stay at the Hilton. Ike had hit her on the drive to the airport and backhanded her on the drive to the hotel. After all, he’s just a man. She told him she wouldn’t take his licks anymore. She told herself she was gone, she was flying. Bloody and swollen when she arrived at the Hilton, she waited for him to fall asleep. She got her belongings and walked out and saw a Ramada Inn across the freeway. She had a Mobil card and thirty-six cents. Despite heavy traffic, she took a breath and ran across the freeway.

“What I mostly remember,” she would say later, “was flashing lights.”

This would become the Motown way.