Honky-Tonk Weekly

#13: Jerry Lee Lewis, "What's Made Milwaukee Famous (Has Made a Loser Out of Me)"

This is the thirteenth edition of Honky-Tonk Weekly, a weekly(ish) column here at the Tropical Depression Substack. You can read previous editions here. Every week, I will listen to and share a country song and write whatever comes to mind. Listen along! This week, we’re drinking and regretting and drinking again with the country side of Jerry Lee Lewis.

Thou believest that there is one God; thou doest well: the devils also believe, and tremble.

James 2:19

“Channels are filled with the most weird, odd, demented, degenerating, debilitating sounds,” the televangelist Jimmy Swaggart told his flock in the mid 1980s. The way he lingered and over-annunciated the long e sound made it clear what he had on his mind, though further clarification was surely gratuitous: The music on the radio was de-monic.

This was before Swaggart’s fall from grace, back when he had at least a claim to be the most famous American religious leader, broadcasting from Baton Rouge to millions of homes in the U.S. (somewhere between two and eight million viewers, depending on who you ask—but surely nearly every American with cable got a look at him flipping through the channels). And also to stations all over the world, eventually to nearly 150 countries—reaching more than 500 million global viewers if you believe his PR department from the time. His ministry was bringing in around $150 million a year. Newsweek proclaimed him the “King of Honky Tonk Heaven.” He was probably one of the most familiar faces in the world.

Rock & roll, Swaggart said, was “veritable pornography over the airwaves.” Punk rock bands, he warned, hung out in graveyards. Rock music and rock magazines, he proclaimed, were the “new pornography.”

After a major televised sermon on the topic in June of 1986, he told the L.A. Times that rock was “pornography and degenerative filth which denigrates all the values we hold sacred and is destructive to youth.”

The Times speculated that Swaggart’s crusade was having an impact on retail after he rebuked Walmart in his sermon:

In the wake of Swaggart’s remarks, at least one major retail outlet, the 800-store Wal-Mart discount department store chain, has pulled 32 rock and teen magazines from its racks as well as comedy albums by Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor and records from such bands as Motley Crue, Ozzy Osbourne, Black Sabbath and Judas Priest.

Walmart denied a connection, but other reporting suggested that the move was at least in part a response to the controversy engineered by Swaggart’s preaching.

His attacks against heavy metal got the most attention, but those Swaggart called out by name also included Elton John, Bruce Springsteen, and the Police.

“I don’t listen to this music,” he explained to United Press International. “But people in (my) organization do listen to it, for research, and they give me printouts, and it’s mind-boggling what’s going on under the guise of freedom of expression.”

Swaggart himself was a musician who put out dozens of gospel albums, selling at least 15 million copies, though it’s hard to know a precise figure, as many of them were sold by direct mail order. In 1980, he received a Grammy nomination for best performance in traditional gospel.

No one would confuse Swaggart’s music with rock & roll, but it was rollicking, in the style of the Holy Rollers (Elvis also grew up Pentecostal, as did Sister Rosetta Tharpe and so many others who helped to birth rock). The gospel bands that backed Swaggart were modern, bombastic, and often radio-friendly. They were happy to use the same instruments that rock bands used. Other reactionary low-church communities, like the Primitive Baptists or the Church of Christ, would never have allowed the proto-boogie that marked Jimmy Swaggart’s style of music—even if some shared the highly emotive musicality in their preaching. They didn’t allow musical instruments in church at all! (The Old Regular Baptists, for example, were suspicious of harmony and musical notation, to say nothing of electric guitars and drum kits). For Swaggart and other Pentecostals, such restrictions were misaligned with their interpretation of the ecstatic mode of worship. The shake and rhythm of their gospel music came directly from the Spirit.

But there was a line, and as with everything in Swaggart’s worldview, the line was firm. “Any Christian who would allow any type of rock or country recording in his home is inviting in the powers of darkness,” he wrote.

While it was kosher to spread the gospel with gospel, Christian rock was no better than rock itself, Swaggart said—it too was “of the devil.” The form itself was tainted. “It’s of the powers of darkness,” he warned. “It’s not of God…It’s the voice of the dragon under the guise of Christianity.”

“My family started rock and roll!” he preached. “I don’t say that with any glee! I don’t say it with any pomp or pride! I say it with shame and sadness, because I’ve seen the death and the destruction. I’ve seen the unmitigated misery and the pain. I’ve seen it!”

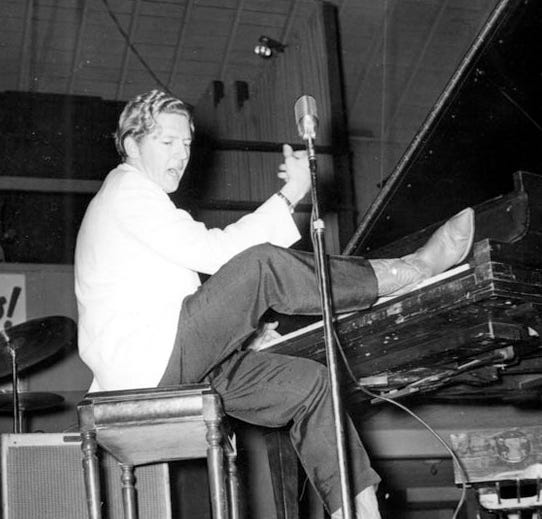

There are many wild things about Jerry Lee Lewis, but the wildness at the center of it all was this: He was certain that he was singing songs that would send him to eternal damnation, and take all of his fans right along with him, but he just kept singing them anyway. He couldn’t help himself.

This is a peculiar and dark form of anguish: To deeply believe in the physical reality of demons, and to be convinced that you are their pied piper. To believe that your own weakness has allowed an evil to overtake your will and your passions. That you have a choice, a more beautiful and righteous choice, but do not have the strength to make it. That the demons are part of you now, that you are in some way inseparable, the way a body is made up in part of bacteria with their own agenda—the way your self, whatever that might be, must exist along with such invisible cohabitants in this shared territory of the body.

And to believe, not without justification, that you are the greatest that ever was. That your talent is celestial. Elvis at the height of his fame would ask you to play piano backstage, just fumble around a bit, and he would watch your fingers as if they were angels on the march.

“There’s only four stylists, and that’s Jerry Lee Lewis, Hank Williams, Al Jolson, and Jimmie Rodgers,” you would tell the interviewer. “Rest of ’em are just imitators.” And the reporter might have thought you were an asshole, but it’s not exactly like he thought you were wrong. This was the astonishing gift, given by God, that the demons were riding.

Jerry Lee was like the ancient preachers and prophets of the first century—touched by some strange power, performing miracles, possessed of a charisma so enchanting that it appears divine, gathering followers, more and more. There was not a word for religion then, there was not a concept of religion like the one we use today, but there was fear and there was awe. There were ineffable powers beyond the world, there was a god or gods, or something, and there were prophets that could serve as mediums.

What Jerry Lee Lewis told anyone who would listen, for nearly his entire life, was that he had found himself a prophet in service of Satan, that he could use his charisma to gather followers, and that he was leading those followers to an eternal spiritual torment that could only be hinted at by analogy to physical torture. His followers might not know that, but he did, and he did it anyway. Because he couldn’t help himself.

He’d launch into sermons in the dressing room before shows, according to Johnny Cash: “I’m out here doing what God don’t want me to do, and I’m leading people to hell!”

This is so grotesque and gothic and premodern that it is almost hard to take him seriously. Jerry Lee Lewis was a ham, and a performer. But he was also an extremist by temperament. He could not grok gray areas, perhaps. He could only reckon the wild edges of wilderness. He was a mean son of a bitch, and maybe he should have spent more time worrying about that. But his anxiety was cosmic: What could explain the incredible force in him but absolute good and absolute evil? There could be no middle ground.

“Satan has power next to God,” he said. “You ain’t loyal to God, you must be loyal to Satan. There ain’t no in-between.”

This was the source of the remarkable back and forth he had with producer Sam Phillips at Sun Records, inadvertently captured by the recording engineer. Phillips tried to convince Jerry Lee that a rock & roll musician could still save souls. “No!” Jerry screamed back. “How can the devil save souls?”

He kept having the same argument, giving the same sermon. It was pathological. He was so monomaniacal on this point that it must have gotten tedious to those around him. He absolutely had to make people understand that he was doing the bidding of Satan with his God-given talent and dooming his audience to damnation by playing rock & roll, but nevertheless he absolutely could not stop playing rock & roll.

As the writer Lawrence Wright put it, Jerry Lee Lewis was “imprisoned by the metaphor of his own life.”

In 1979, the music journalist Robert Palmer asked Jerry Lee if he still believed that he was going to Hell for playing rock & roll.

Lewis looked him right in the eyes. “Yep,” he said. “I know the right way. I was raised a good Christian. But I couldn’t make it … Too weak, I guess.”

In 1982, Jerry Lee attended a family funeral, where his cousin Jimmy Lee Swaggart preached a sermon.1

“Whoever among you believes you wouldn’t go to Heaven with Uncle Arthur if you died today, come forward,” Jimmy Lee said in closing.

Jerry Lee walked up and stood face to face with his cousin. They hadn’t seen each other in some time.

“Will you accept Christ as your savior?” Jimmy Lee asked.

The two cousins were born eight months apart. Growing up in Ferriday, Louisiana, they had spent their childhood as close and inseparable as twins.

Jerry Lee said nothing in reply, still standing there in silence, face to face with Jimmy Lee. After a time, he turned away.

They came from a bootlegging family in Ferriday, a rugged town a few miles from the inlet of the Mississippi River that marks the border with Mississippi. Both of their daddies had gotten in trouble with the law after a moonshine still was busted but managed to be there when their sons were born. In the case of Jerry Lee’s father, Elmo, this required an escape from prison.

Elmo was a cotton farmer, carpenter, and cattle rustler who worked odd jobs and scrapped together a living. He loved to sing.

Elmo’s brother in law was Sun Swaggart, Jimmy’s father. Sun played the fiddle and spent time as a fur trapper and pecan picker before eventually running a gas station and then a grocery store. As a young man, he had some success as an amateur boxer. He also played community dances, with his wife Minnie joining him on rhythm guitar while he played the fiddle.

Sun Swaggart was a hard man. “If [Jimmy] challenged his father,” Jerry’s sister Frankie Jean told Lawrence Wright, “Uncle Sun would put on boxing gloves and just deck him.”

Not long after Jimmy was born, an evangalist and her daughter set up a tent in the vacant lot across from where Sun was running a gas station. They went knocking door to door to let people know: They could come find good news (and good music) with the Assemblies of God. Sun had only been to church once in his whole life, but when he heard the gospel music coming from that Pentecostal tent, he felt compelled to see what it was all about. When Sun and Minnie went to go check it out, they brought their instruments.

The Pentecostal movement was a wild affair and was looked on with suspicion by the more upright citizens in towns where they worshiped. Many of the congregants were poor; people spoke in tongues; some meetings included Black worshipers alongside white worshipers, which helped to create a radical fusion, very much including the music. The charge in their services was undeniable, and scary—with an edge of the forbidden. The old joke was that a baby boom would happen nine months after a tent revival came through.

The Swaggart family, along with the Lewis family and other kin, became diehard converts, and many of them became evangelists themselves. Jimmy and Jerry Lee went to Sunday school together, along with another cousin they were close with, Mickey Gilley, who would go on to become a Country Music Hall of Famer.

One Christmas when they were around ten years old, all three boys started messing around on a family member’s piano. A momentous day in rock, gospel, and country music history, as it would turn out. A few months later, Elmo Lewis mortgaged their house to buy a piano for little Jerry Lee. The bank eventually foreclosed on the house. They kept the piano.2

As they got older, Jerry and Jimmy started going to Haney’s Big House, a Black club in the “Chocolate Quarter” in Ferriday, where they got an education in Southern Black music. They’d sneak in and shine shoes and soak up the atmosphere until Haney kicked them out.

In their early teens, Jerry and Jimmy, developed an act as a duo, playing piano together—Jimmy on bass and Jerry on treble. They won talent shows all over and started playing at local clubs. Around this time, they also began to break in to local stores and steal scrap iron from people’s backyards. They were still God-fearing, but they were also teenage boys. They were wayward rednecks, thick as thieves—and when they played the piano, the people went wild. A kind of wild, perhaps, closest in spirit to what happened under the tent at an Assemblies of God revival.

One night, when Swaggart was playing on his own at Haney’s big house, he had an experience that sounds not so different from the feverish religious experiences he was having early in his life.

“A strange feeling came over me,” he writes in his memoir. “I was able to do runs on the piano I hadn’t been able to do before. My fingers literally flew over the keys. For the first time in my life, I sensed what it felt like to be anointed by the Devil.”

But the cousins still felt the call of the Lord, even if it hadn’t quite hardened their behavior. Even as Jerry Lee took jobs at hellbent juke joints, he was preaching as early as fifteen, and dropped out of high school to go to Bible college. But in short order, he got kicked out for playing a boogie version of a gospel number. So he went back home to preach on the streets.

Meantime, it was, at first, Jimmy Swaggart who resisted the call. I would say that both cousins found the path best suited to their talents, but it is irresistible to wonder: If the contingencies had worked out a little differently, might Jimmy have been a rock star and Jerry Lee a star preacher?

In any event, even as he strayed, it nagged at Jimmy: Would the Rapture come and he be left behind? At seventeen, after dropping out of high school, he began preaching. He was good at it. When his cousins Jerry Lee and Mickey watched him, they wept. He kept preaching.

Jerry Lee might have kept preaching, too, but in late 1956, his dad drove him to audition in Memphis for Sam Phillips at Sun Records (the trip was funded with the sale of thirty-three dozen eggs). Stuff changed after that. Jerry Lee came back to Ferriday driving in a brand-new Cadillac. “But what about your soul?” Jimmy asked his cousin.

When Jimmy Swaggart was a little boy, he made a promise in church one day. He asked the Lord for the gift of playing the piano and swore that he would only use that gift to glorify God, never for the world.

He said his prayer aloud, again and again—too loud for Sun Swaggart’s taste, who punched his child to try to shut him up.

“If I ever go back on my promise,” little Jimmy Lee Swaggart told the Lord, “you can paralyze my fingers.”

One curiosity: According to Swaggart, when Jerry Lee broke out and began selling millions of records, Sun Records producer Sam Phillips tried to get Swaggart to sign on with Sun as a gospel singer. Swaggart was tempted by Sun’s offer. A gospel line at Sun Records! At this point, Swaggart had a wife and a three-year-old son. When he wasn’t on the road preaching in a beat-up Plymouth on its last legs, he worked as a swamper on a dragline. It total, he was making about $30 a week (adjusting for inflation, that would be around fifty percent of the poverty line today). The family had no home of their own. As Swaggart traveled to spread the gospel, they relied on others to put them up or stayed in church basements. If there was nothing else available, they would find a cheap motel. Sometimes they went to bed hungry.

But Swaggart declined the offer from Sun. He was called to preach, he said, and he had to stick with it.

This moment, if this is really how it happened, remains a little hard to understand. Swaggart is clear in his memoir that the idea at Sun would have been for gospel music of the sort he was comfortable with. Money aside, a record on Sun would have given him more exposure for his ministry. Swaggart himself is not quite able to explain the logic. It’s just that the Lord told him to say no (the God that Swaggart worships is highly involved in his daily affairs).

“I knew it was the Lord, but I couldn’t believe He’d tell me to refuse this offer,” Swaggart wrote later. But he could only obey. It was as if his mouth was wired shut.

In any event, Swaggart eventually sold lots of gospel records on his own. Jerry Lee, always bitter, was unimpressed.

“Mickey and Jimmy, they don’t have the depth I have,” he declared. “I got all the talent. They just got the scrappings.”

Jerry Lee was married seven times, but you know about the third one: When he was twenty-two he married his first cousin once removed, who was thirteen and in seventh grade at the time. She still believed in Santa Claus. When it came out while he was on tour in Europe, the British press was horrified. She said she didn’t see what the fuss was about. “Age doesn’t matter back home,” she told them. “You can marry at 10 if you can find a husband.”

For context, such as it is, when Jimmy Swaggart was seventeen, he married a fifteen year-old girl he met at church; they remain married today. Or the Swaggarts say she was fifteen, anyway—Jimmy Lee’s sister Frankie Jean claimed to Lawrence Wright that the girl was actually fourteen at the time. Frankie Jean herself got married when she was twelve. “We’re all kind of earthy, to say the least,” she said.

There were a lot of famous men at the time doing a lot of bad stuff when Jerry Lee got hitched to his little cousin, but the stink of this particular scandal destroyed his career, which was more or less in shambles for a decade.

That his comeback came via country music makes a perverse kind of sense. No one is going to defend child brides—and by pretty much all accounts, Jerry Lee was not a good guy (he could also reportedly be a violent husband, and was later suspected by some of killing his fifth wife). But there was an element of culture clash in the intensity of Jerry Lee’s dismissal from polite society. His perversity and deviance was morally troubling, sure, but his bigger problem is that it was trashy. The country music industry might have been even more gossipy and moralistic, but it had always had a forgiving and protective attitude toward its trainwreck country boys.

It was also music that Jerry Lee felt attuned with, and always had—at least the sort of country music played by Hank Williams, one of Jerry Lee’s favorites (and another trainwreck, of course, whose behavior may have been even worse than Jerry Lee’s). “I played that good kind of country,” Jerry Lee said later, “not that other kind.”

His mother loved Hank and Jerry Lee used to sing his songs as a boy. There was something in Hank’s brand of emotive trouble, seeped in both spirit and sin, that made him feel like a kindred spirit. Jerry Lee always called him “Mr. Williams.”

“I felt something when I listened to that man,” he said. “I felt something different. … I listened to Mr. Williams and I listened real close.”

As he got better on the piano as a teenager, he played Hank Williams songs over and over. He hoped to meet his hero, and he might well have, but Hank died when Jerry Lee was seventeen. “You can’t fake feelin’,” Jerry Lee said. “Hank Williams delivered a sermon in a song, and nobody else could do that, nobody else could touch it. He was like a preacher, that way.”

The closeness Jerry Lee felt continued even after Hank died, and he kept a photo of him on his dresser for years. Jerry Lee’s way of making music, and what that music meant, was a lesson he took from Hank, he said: “It takes their sorrow and it takes mine.”

This was probably a more emotionally healthy point of view, if still painful, than worrying you were doing the bidding of demons. Hank almost seemed to take on people’s suffering and sin and give it relief in song; Jerry Lee, in a different way, did the same. “That’s it,” Jerry Lee said, “Hank got them up off their knees and Jerry Lee got them to dancin’.” When Jerry Lee was feeling less certain about his doom, he would remind himself that he could lift the blues off people—could that really be the work of Satan?3

The unhinged fury and freaky Holiness fervor in Jerry Lee made him a kind of platonic exemplar for the burgeoning genre of rock, but if things had sorted out a little differently, he could have well followed in the footsteps of Hank and wound up being an all-timer in country music. In fact, this is what he attempted first, before he ever tried out for Sun Records.

First, he drove to the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport and auditioned for country music great Slim Whitman. Slim passed—too much boogie for his taste. So next he tried heading out to the country music big-time in Nashville. He attempted to tone things down to fit the more conservative vibe, but once he sat down at the piano, he was too soulful a player. Everyone kept telling him to pick a guitar instead. I’m not sure exactly how long he spent there, but it was a decent amount of time, trying to break through anywhere he could, but he found no takers in the country music industry. “I never did like them rhinestones,” he said later. Sam Phillips in Memphis saw his genius; Nashville missed it.

So it must have felt like a redemption of sorts when he returned to country music more than a decade later. His music stardom derailed, fresh off a theatrical run playing Iago in a musical adaptation of Othello (!),4 he tried his hand at a country song—a last desperate effort to regain relevance.

He covered “Another Place, Another Time,” penned by Jerry Chesnut— “the kind of thing Hank Williams would have wrote,” he said. Del Reeves recorded it first but it went nowhere. But as Jerry Lee liked to remind people, “A song can be good, but it can’t be great till I cut it.” His version was a surprise smash hit on the country charts, and Mercury rushed him to Music Row to record more country music. The album, Another Place, Another Time, shot up to #3 on the country charts. The Killer was back.

The follow-up single to “Another Place” was “What Made Milwaukee Famous (Made a Loser Our of Me),” written by Glenn Sutton—another hit, reaching #2 on the country charts. The song’s particular brand of wallowing is vintage Jimmy Lee, the story of his life in his telling: He has regrets, the fault is his own, but he just can’t help himself. “I know I should go home,” he croons, “But every time I start to leave / They play another song.”

Many tearjerker country songs hinge on counterfactual thinking. Things are grim; there is an alluring sweetness to the false comfort of what might have been. We are participants in history, agents in the arrow of time. As Ricky Skaggs sang, “You can’t control the wind but you can adjust the sail.” The wind might be a bummer, but it’s sadder still if you know you’re the one who failed to adjust the sail. If your boat is off course and it’s your own dumb fault. Trouble has a particular kind of hurt when it’s trouble of your own making.

It is deeply hard to reckon what free will would be or would mean in the anxious theology and metaphysics of Jerry Lee Lewis. But he could channel that particular trouble, that particular sorrow.

“Made a foooool out of me,” he sings, howling the notes of his lament. I am about as big a fan of Gary Stewart as you can be, but I have to admit that Jerry Lee was able to find the brutal register of Stewart’s crooning, several years before Stewart broke out as a honky-tonk star. I am rendered cussing in appreciation. His sorrow and mine: he lifts the blues off me.

It is a tour de force—the whole album is—deeply rooted in the songs of his childhood. No doubt many of the people who loved that record were God-fearing, church-going folks. But it must have wounded him to know that when his cousin preached against worldly music, he made no special exception for country. The Grand Ole Opry might have broadcast from a church, but this was still the Devil’s work, Jimmy said. That it was his cousin—a kind of soulmate or mirror twin, their lives intwined as opposites—who condemned him must have hurt. But what really hurt was that Jerry Lee had the same sort of fear: He was back, singing country like Hank instead of rock & roll, but his trouble was the same—the demons, he thought, still had ahold of him.

In the summer of 1944, Jimmy Swaggart, then nine years old, began speaking in tongues. He spoke in Japanese and German, his family claims, and then offered interpretations in English of what had come from his mouth: A prophecy of a powerful bomb. “A year later,” he wrote in his memoir, “when the two Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed, nobody thought the prophecies were childish anymore.”

As an adult, he said, he spoke in tongues every day.

“He was preaching on the edge,” a preacher in his ministry said. “There is something glamorous about being on the edge of anything…he was going to the limit every time.”

Was it inevitable, then, that Swaggart’s weakness reached as far out to the wild edges as his awesome power? That his demons were as untamed and weird and kinky as the Holy Spirit within him? That like his cousin, he knew he was a sinner but felt an otherworldly compulsion to scratch his all-consuming itches? That, like his cousin, he knew it was wrong and did it anyway. Because he could not help himself?

You cannot watch him preach without thinking about the scandals that would bring him down later, but you can watch him preach—there are plenty of clips on YouTube of Swaggart in his prime. He was perhaps the most erotically charged performer of the 1980s, sweaty and in command of his own jitters in a way that reminds me of Little Richard. He was unpredictable and rude. He was country. To gussy things up in his presentation could only be a betrayal. He was a millionaire now but he still spoke and moved and sang as he always had—the itinerant, destitute, redneck high-school dropout screaming at the tent revivals out in the swamplands.

His theology was Restorationist and so of course his manner was shocking. His message was shocking. His passion and his gift was conjuring the ancient shock of the first-century preacher. Was the truth not shocking? Was the good news not awesome, in the literal sense of the word? John the Baptist was shocking, as was Jesus, and then his apostles.

Swaggart asked for checks, of course, but he was not offering the sunny prosperity gospel of Jim Baker. Modernity itself was a kind of Satanic pollution that had undone the righteousness of the primitive church. (Modernity here defined as the last, oh, nineteen hundred years or so.) He preached fire and brimstone, he preached of the coming Rapture, but he also preached of a kind of slow burn of earthly wickedness: centuries of corruption, deviance, and an all-too-human lust for power. The only response to such perversion was primitivism. To look back to the early Christians gathered in their homes, hearing the stories of the apostles, particularly weird people in a particularly weird age, preparing for the return of a messiah still in living memory, all of them still shimmering and trembling in the miraculous, many of them dirt-poor, many of them shunned, many of them wretched, unshakeable in the mystical and unproveable conviction that the world we think we know is upside down—that the last shall be first and the first shall be last.

If all that sounds fanciful, a childish nostalgia for an era we cannot possibly understand, then wait. Wait for the Holy Spirit. That could be your codebreaker, your channel to the divine, your psychic thread to the ancients and the apostles.

On the day of the Pentecost, recall, the apostles were gathered when a violent wind came from Heaven. They were filled with the Holy Spirit, and they spoke in other tongues, yet all could understand them. Some onlookers thought they were drunk, but they were not drunk (it was too early in the morning to be drinking, Peter pointed out). It was just strange, is all. The holy strangeness of the Spirit, of intervention in the natural world. If it doesn’t look like madness to the world, then surely it is no miracle.

Swaggart knew this story in his sweaty pores. If the end was not so far away, if the deadline was closing in on the urgent matter of souls, then surely the time has come to restore these ancient gifts of spirit and healing and prophesy?

This was a hard brew. It was run and re-run on cable, in weekly sermons and up to seventeen different programs he hosted. If you channel surfed, you’d inevitably find him. He claimed that his message was broadcast to “more than half the homes on the planet.” He claimed to be saving 100,000 souls a week in his race to evangelize the world before the end of days. Time was running out.

Meantime, the universities and the corporations and the media and the liberals and the mainline churches could only gawk in horror. They veered between making fun of him and warning that his demagoguery was dangerous.

It didn’t bother Swaggart. “You can write your poor little old pitiful pukish pulp in your papers if you want to,” he told the media, “but you can stop what I’m preaching about like you can stop a Louisiana hurricane with a palm branch.”

“Yessir, goin’ to hell. The Bible tells us so.”

—Jerry Lee Lewis, interview in Country Music, 1979

The skepticism of rock music or other popular music forms among American evangelicals is overdetermined. And in some cases—like Jimmy Swaggart—I mean, I’m sorry, it can get pretty silly.

Jerry Lewis was never quite static in his views and he was a shifty talker who was always contrary, so it’s no surprise that later in life, he made this point himself. Rebuffing an interviewer in 2015, he said, “How can it be the devil’s music? Satan didn’t give me the talent. God gave me the talent, and I’ve always told people that.” But the question clearly still haunted him. In the same interview, he said that he was still worried about going to Hell; his seventh wife, Judith, interrupted before things went further: “He’s going to Heaven. We’re going to change the subject.”

The idea that rock was inherently Satanic always seemed especially weird to me coming from a preacher with a Holiness background like Swaggart. The preaching, worship, music, and prayer of the Pentecostal church in both white and Black communities was foundational stuff in rock & roll. Elvis, the story goes, heard Brother Claude Ely preach and sing as a boy at a Pentecostal revival. He saw the way he moved and never forgot it. Little Richard took inspiration from Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a straight-up gospel singer in the Church of God in Christ tradition (she invited him onstage to sing at one of her shows when he was fourteen). Sun Swaggart was drawn to the revival tent by the music. And like it or not, gospel infused with the Holy Ghost sounded like early rock & roll.

The connection is perhaps most clear in the music of Jerry Lee Lewis himself. Rock & roll is unthinkable without him; his music is unthinkable without his Pentecostal raising. Perhaps it was precisely this closeness that frightened Swaggart and his cousin.

But. I mean. Genre preference is rickety territory in theology. Who knows what kind of music demons might listen to—or angels? Perhaps music in the coming Kingdom of God is not explicable in the sonic math problems of the earthly realm. Perhaps such music is not music at all in any way we would understand.

When Robert Palmer pushed back on Lewis and questioned why playing rock & roll would damn him to Hell, Lewis looked at him like he was a fool.

“I can’t picture Jesus Christ doin’ a whole lotta shakin’,” he said.

Jerry Lee was dead serious but this response is a punchline of sorts. I just find it more sad than funny.

According to tradition, Jesus is both God and the son of God—consubstantial—and also he is the Holy Spirit that reveals itself to God’s creations. He sacrificed himself and rose again; he foretold the unfathomable Kingdom of God. If you believe in the radiant truth of that story, then his opinions on the rhythm sections of pop bands seem not just anachronistic but wholly beside the point. That’s what I find a little sad. Jerry Lee’s relationship with Jesus was fundamentally neurotic.

Country music, probably more than any of the other worldly pop music forms in America, often seemed to want to have it both ways. You could sing very straight-ahead Christian music at the Opry or even at a honky-tonk in a way that would have been unthinkable at a rock club. And the hope and hurt in Hank’s voice sounded awfully close to the same, whether he was singing “Your Cheatin’ Heart” or “I Saw the Light.” Country music from the very beginning defined itself by its audience. God-fearing people with old-fashioned attitudes like to buy records, too. To call the entirety of country music Satanic requires an inflexible certainty that seems nothing so much as worldly, even tawdry.

But Jerry Lee, of course, was under precisely this sort of delusion for most of his career. There was no dabbling in the divine. There was no mode of ecstasy or reckoning of metaphysics in which the sacral and the obscene might turn out to be inseparable. There ain’t no in-between. That was his lodestar.

To interject and editorialize a little more here: He was wrong! It’s not true! The truth is, I think, there ain’t nothing but the in-between. Who could find meaning in an A&R department God, filing records into good and evil? If God is the all-encompassing truth of everything, surely there is God in every music, alongside and in fusion with fallen man: sacred, obscene, groovy, carnal, divine.

But ain’t no in-between was the only truth Jerry Lee could settle on. And Jimmy Swaggart, too, or so it seems. Even when his demons got the better of him and he paid a prostitute in a by-the-hour motel off Airline Highway outside of New Orleans to take off her clothes and fondle herself, while he pleasured his body that was made, like every body, in the image of the Lord. Every power in the cosmos works in mysterious ways.

There was no in-between. According to Swaggart, country music was just the same danger in a different package.

Preach, Jimmy:

“Satan has another lever that he’s pulling and it’s called good old country music. Some of you sat in this place tonight and you think, ‘I like my country music.’ But when you do, you’re liking triangles of adultery, dope, alcohol. Hell, filth! That’s what you’re liking.”

Jimmy told his audience that he knew some of them nodded along and said “amen” when he condemned rock, but still blared country on their radios, to their doom: “I believe that country music today is as diabolical—and destroying as many people—as rock music….It’s designed a little different because it’s reaching for a different audience, but Satan knows exactly what he’s doing.”

It was all a part of the same “diabolical scheme of Hell.” The “design of country music…was just as dirty in its own right as hard rock.” Toss all those records in the rubbish. Keep close watch on your children. Just like rock & roll, country music had a power that could draw you in.

And Jimmy had a point, at least, about the music’s power. Cue up “What Made Milwaukee Famous.” Jerry Lee performing country songs, like Jerry Lee performing just about anything, had a drawing power so electric and orgasmic—so physical in its force—that you could just lose yourself. And to lose yourself is scary business for us poor sinners.

To lose yourself to the wilderness of the spiritual, in unison with God: that was frightening in its own way, but it was good, it was shielded with a goodness beyond all measure. It was shielded in a glory most high. Jimmy Lee Swaggart wanted to get on every TV station in the whole wide world because he could take people there, he could shield them and maybe even shield himself.

But Jimmy knew, or at least I am convinced that he knew: The Spirit was mighty in him, but he got just the scrappings.

Jerry Lee took you to a different place, even deeper into the wilderness. It wasn’t Hell, not really. Never was. But Jerry and Jimmy, both of them, they were frightened of this other place, of the way the people screamed when Jerry sang, of the unshackling that Jerry commanded in a body overtaken by his music. When there’s a whole lot of shaking going on, who knows what might come out? Perhaps their greatest fear was that something in the release and fury of that music had some sway on their private torments. On their deviations. On their guilt. On what we would call their demons.

Jerry Lee loved his talent, but it scared him. “It makes you search your mind sometimes,” he said. When he performed, he could make them jump; he could make them scream. It was like a mighty wind; it was like a lake of fire. Jimmy, like his cousin, knew its power. Like his cousin, he was afraid. Hell was the only story they knew that could make sense of that awesome heat.

The account that follows is from Lawrence Wright’s wonderful piece on Swaggart, compiled in Wright’s book Saints and Sinners, which was a valuable resource for this post.

As described in Wright’s piece, where I got much of the information for this section.

As recounted by his biographer Rick Bragg; I’ve seen the “lift the blues” line attributed directly to Lewis, but that may be Bragg paraphrasing what he said.

“I wonder what Shakespeare would have thought of my music,” he mused.