This is the second edition of Honky-Tonk Weekly, a weekly column here at the Tropical Depression Substack. (It used to be “Honky-Tonk Tuesday” but I’ve decided maybe “Weekly” sounds better? What do y’all think?) Every week, I will listen to and share a country song and write whatever comes to mind (previous entry here). Listen along! This week, like a fiend with his dope or a drunkard his wine, we’re down in the pit with Merle Travis.

We are almost smothered

I spent the morning reading about coal mining disasters. I don’t know why I do these things. In 1902, an explosion of methane and coal dust at the Fraterville Mine near Coal Creek in Tennessee killed 184 men and boys. Most died instantly. A small number survived until the afternoon, when they ran out of oxygen. They wrote letters to their families. And so when they recovered the bodies, they recovered the letters.

One letter began: “Dear Wife and Children: My time is come to die. I trust in Jesus. Teach the children to trust in Jesus. May God bless you all is my prayer. Bless Jesus it is now 10 minutes till 10 and we are almost smothered.”

Addressing his two sons, he added, “My Boys, Never work in the coal mines.”

“We are all praying for air to support us but it is getting bad without any air,” wrote another. He wrote goodbyes to Lily and to Jimmie and to Horace. “Oh God for one more breath,” he wrote. “Ellen remember me as long as you live. Good Bye Darling.”

An orphan addressed his letter “To Everybody.”

“I have found the Lord,” he wrote. “Do change your way of living. God be with you.

Good Bye.”

Good old difficult days

Merle Travis was from Muhlenberg County in southwest Kentucky, although fans typically thought he was from the southeastern region on account of his lyrics. Merle thought this was a strange mixup. “I’ve sung about Heaven all my life and nobody ever thought I was from there,” he remarked in his autobiography.

When he was a baby, his father quit his job tobacco farming to work in the coal mines. He spent the rest of his working days down there, which Merle believed he always regretted.

The first house Merle remembers living in was owned by an old Black couple, former slaves. When he was around eight years old, Merle learned to play the banjo. His mother worried about his father “learnin’ that young’un them ol’ songs, that’s takin’ the name of the Lord in vain.” His father responded, “I ’spect the Lord enjoys a little fun once in a while.”

The Travis family never owned so much as a mule for transportation. They had no electricity or plumbing. “We never had a radio,” Merle wrote later, “and we never had rugs on the floor.”

When Merle heard the miners sing in their tent setup at the nearby camp, he recalled, “it was something beautiful floating to me from out of the black, mysterious night.”

When he was around twelve, his brother Taylor built his own guitar, and Merle started messing around with it. One summer, a couple of young men, Mose Rager and Ike Everly1, came to work in the mines and brought their guitars with them. They taught Merle a style of guitar picking that he took to and eventually popularized, becoming such a maestro that it came to be called “Travis picking”—using his thumb to pluck alternating bass notes while picking a higher, rhythmic melody with his index finger simultaneously.2 If you want a rabbit hole, there are lots of clips of Merle in action.)

One morning, in January 1937, as Merle was walking out the door, his mother asked,“Will you take that job at the mines if your Pappy can get them to hire you?”

“I don’t reckon so, Mammy,” he said. He was penniless, but he had a telegram in his pocket, with a gig awaiting him to play with Clayton McMichen and his Georgia Wildcats in Columbus, Ohio. He made it there with some borrowed money and a secondhand suit and never had another job but picking and singing.

Later, when he released his 1963 album, Songs of the Coal Mines, Merle had his older brother John write liner notes. “Now we older ones can listen with nostalgia for the good old difficult days,” John wrote, “and the younger ones can doubt a little, laugh a little, and be a little better informed about their elders and their pitifully happy era.”

Till the stream of your blood runs as black as the coal

“Dark as a Dungeon” was written by Merle (though one always wonders about traditional roots with a song like this) for Folk Songs of the Hills, his 1946 box set of four 78s. It became something of a standard during the folk revival and became newly famous when Johnny Cash covered it on the 1968 live At Folsom Prison album. It’s the one where Cash loses himself and starts chuckling mid-song, then says something about, “I know, hell” (or “I know hell”) in response to something someone in the audience says. Dolly Parton also covered it beautifully (if flavored with too much melodramatic schmaltz for the material, IMO) on 9 to 5 and Odd Jobs. Here’s Willie Nelson’s take. And there are dozens of others.

But not even Cash’s mythic resonance can beat Merle’s original, in my book. There’s a sneaky quality to Merle’s genius that comes through on all his work. He was an all-time picker and a solid showman, but there is a subtlety to his style. It feels like you are happening upon your neighbor just messing around, and you wander over with a beer in hand, and as your mind relaxes and your ears soften and your eyes adjust, you find yourself suddenly in awe. Something beautiful floating to me from out of the black, mysterious night.

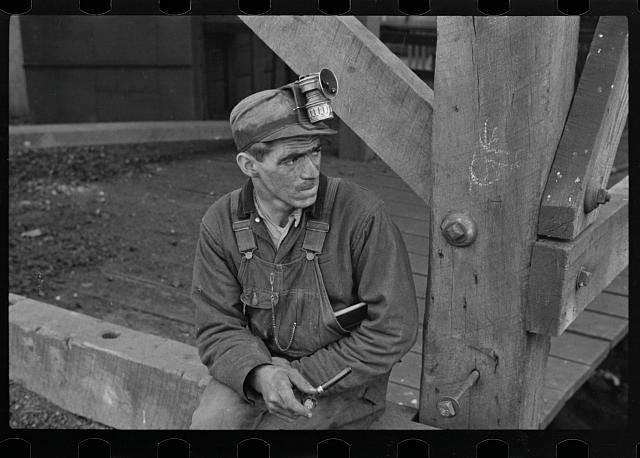

And with this one in particular, it is the aw-shunks simplicity of his delivery that makes the performance so arresting and haunting. Because while this became a rallying song for miners looking to improve working conditions (“danger is double and pleasures are few”), the dark import of the song is that on some level, some miners became addicted to the way of life, despite the danger and the miserable conditions.

“Seek not your fortune in the dark dreary mines,” Travis sings, and we’re in familiar terrain of hardened admonishment here (“My Boys, Never work in the coal mines”). But the next line is a chilling twist: “It will form as a habit and seep in your soul.”

Here’s the song’s black and bleak vision of the circle of life:

Like a fiend with his dope and a drunkard his wine

A man will have lust for the lure of the mines

I hope when I’m gone and the ages shall roll

My body will blacken and turn into coal

Then I’ll look from the door of my heavenly home

And pity the miner a’ digging my bones

I’ve taken a number of trips to southeast Kentucky to report on the lined-out hymnody of the Old Regular Baptists. One thing that coalminers would often say: “You go in the ground, you’ll never want to do nothing else.” Something else I noticed: In Appalachia (and this was well before the pandemic), people say “be careful” for “goodbye.”

It is very tempting to tell a just-so story about the sound of singing in the hollers. About the particular way the ballads and psalm singing of the Old World sounded in the rough-and-tumble hill country in the American frontier. About the way the sound echoed from one holler to the other between the stillness of the mountains, decorated with Kentucky birdsong. The particular sound of those old songs when sung by desperate men in coal camps in company towns, melodies rushing out like escaped prisoners. And the particular sound of the songs when sung at the bottom of a deep, black hole in the ground. A hole dug with all the fury of the capital. The black beat of profit. The black beat of pride. The songs were not as old as the mountains, but they felt that way. The way it could sound like an angel with the sweetest expression of longing, or salvation, from the depths of Hell. We will not tell these just-so stories. We will listen to the songs.

Here’s an Old Regular Baptist speaking about his experience in the mines, recorded by Jeff Titon as part of the Smithsonian recordings of Old Regular Baptist singing:

A lot of times, while I’m at work—when you’re back underground in the coal mines, there’s a sound there…that you don’t—it’s amplified, or—you don’t get everywhere. Many times, many times, I sang—continually, almost. Because my salvation makes me happy. And it causes me to want to sing.

postscript: Merle Travis appeared in a few “soundies”—basically proto- music videos that were produced in the 1940s to be used on visual jukeboxes, known as Panorams. You’d put in your coin and watch a 16 mm projection. Some also showed stripteases. Here’s Merle singing “Dark as a Dungeon” some years after the original 1946 version above.

Merle stayed friends with the families and recounted much later hearing Ike’s boys sing a few songs at Mose’s house in 1956. They were hoping to make it in the music business. Merle thought they were good. You can probably guess the punch line: Ike’s sons were the Everly Brothers.

“I’d probably be looking at the rear end of a mule if it weren’t for Merle Travis,” Chet Atkins once remarked.