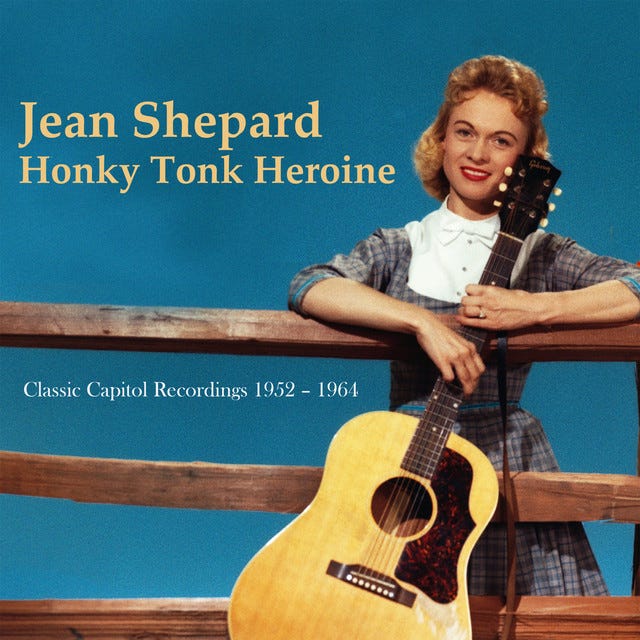

This is the first edition of Honky-Tonk Tuesday, a weekly column here at the Tropical Depression Substack. Every week, I will listen to and share a country song and write whatever comes to mind. Listen along! I realize it is Thursday today, not Tuesday; I had two sick children this week and got waylaid. For our debut, we’re whooping, hollering, and bringing the lowdown men to their knees with Jean Shepard.

Jean Shepard wasn’t much more than five feet tall. When she met her hero Hank Williams early in her career, she told him she wanted to be a country singer. “Oh yeah?” he said. “Well, there ain’t much room in this business for a woman country singer.” She was a teenager, and perhaps that hurt her feelings at the time, but the public record suggests that she was not a woman who gave a damn1 about such talk as that. “I’m fixin’ to change that,” she told him.

She was a wicked yodeler and an old-school juke-joint warbler. She sang songs about how men were the root of all evil, and had a rare cheating-heart number from the perspective of the mistress. One of the few women inducted into the Grand Ole Opry in the early decades, in 2015 she became the second performer ever to be a member of the Opry for sixty consecutive years. She was a spitfire. “Sixty years ago, I loved what the Grand Ole Opry stood for,” she said as the Opry was celebrating her achievement. “I still love what it stands for, but not quite so much. Isn’t it terrible being so truthful?”

Our song this week, “Two Whoops and a Holler” (see Spotify link above), is a proto-feminist honky-tonk banger from 1954 (!). I played this for my wife Grace and she was immediately smitten. Like, same as it ever was.

The songwriter’s credit went to Clyde Wilson. I suspect that means Ferlin Husky, a frequent collaborator with Shepard at the time, did the writing.2 (I wonder, too, whether Shepard helped Husky with the lyrics, but who knows.)

In some ways it has the flavor of a novelty song, but it’s rescued by Shepard’s fierce performance. She would have hated hearing this, but there’s a bubblegum sassiness that gives this song an extra kick and a dark ironic underbelly. Kitty Wells stuck up for honky-tonk angels and asked us to sympathize, but Shepard seems to be scripting a revenge flick.3 Let’s call it “The Wrath of the Honky-Tonk Angels”—slashing lace curtains with broken beer bottles, double kicker boots square on the throat of every no-good man.

And maybe the good ones too? After ripping the double standards around rough-and-tumble living and lamenting the uneven balance of household labor (same as it ever was), the third verse rallies the ladies to make men “walk on their knees and sleep out on the ground” and concludes “they're lower than a hound / I hope they croak, it ain't no joke, they're the lowest thing in town.” I hope they croak! Love it.

For all the slapstick yapping, Shepard is a pro—the consummate honky-tonk singer, she finds the perfect texture on every line and knows when to add some pepper, like the throaty hiccup to open the chorus, just the bare trace of a yodel.

My only complaint about this performance is the note she holds at the very end, which sounds incongruously like a Christmas song. Very awkward. We’ve brought men to their knees and then Mrs. Clause is serenading Santa for some reason.

Ollie Imogene Shepard was born to sharecroppers in rural Oklahoma during the Great Depression, one of ten children. From her interview for Ken Burns’ documentary on country music:

I chopped corn and I picked cotton. And it didn’t hurt me a bit. But every Saturday night, we’d take an hour off and turn on an old radio and listen to the Grand Ole Opry.

When she was around eleven, the family moved to a town about 100 miles north of Bakersfield, California. Shepard formed a band with high school friends called the Melody Ranch Girls and got her big break when she caught the attention of country star Hank Thompson, who was on tour in the area. She was invited (or in some tellings, invited herself) to sing on stage with Thompson, who then helped convince Capitol Records to sign her when she was around eighteen years old. Her parents signed over legal guardianship to her collaborator Ferlin Husky so she could go on tour.

Country aficionados will note that Hank Thompson had a hit early in 1952 with “The Wild Side of Life,” which inspired the answer song, “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels,” an all-time classic released by Kitty Wells that June.

“I didn't know God made honky-tonk angels,” sang Thompson, grousing that a woman he loved has ditched him to party in the nightclubs, choosing the wild side of life over becoming a faithful wife.

“It wasn’t God who made honky-tonk angels,” Wells sang in response. It was men! The narrator in her song had been a trusting wife, only to find out that married men run around cheating in the honky-tonks: “From the start most every heart that's ever broken / Was because there always was a man to blame.”

Shepard was signed around the time this song took off, and the comparison to Wells is inevitable. It’s possible that the success of “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels” helped entice Capital to back Shepard, in order try to corner more of that market. Perhaps “Two Whoops and a Holler” was even written with that goal in mind. But “Two Whoops,” despite being hammier, is also just a weirder and nastier song than “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels.” I like both, but the tone of “Two Whoops” suits the rugged, gritty twang of Shepard’s classic honky-tonk style. You can hear the seeds of Loretta Lynn in Shepard’s raw edge.

Shepard was a hardcore traditionalist, which led to some dry spells in her career. As fashions changed toward slick Countrypolitian and the Nashville Sound, Shepard held firm to her roots, which cost her sales and at times put a dent in her reputation. She’s still wildly underrated, if you ask me. She just would not and could not abide the encroachment of city-slicker pop production into country music.

These are always doomed battles, of course. That’s just what music does: change. Shepard was standing athwart the train a comin’ yelling stop.

“I’m very adamant on how I feel about country music,” she told The Tennessean in 2015:

And I don’t care who knows it, and I’ll tell the world. Country music today is not the country music of yesterday. … Candy coated country don’t make it. They candy coat it and try to be something they ain’t. Well it ain’t gonna work my friend. …

It’s a good fight for a good cause and I mean that with all my heart. Today’s country is not country, and I’m very adamant about that. I’ll tell anybody who’ll listen, and some of those who don’t want to listen, I’ll tell them anyway. … Country music today isn’t genuine.

Even if my tastes are closer to Shepard’s than her enemies, the official position of the Tropical Depression newsletter is general opposition to dead-end authenticity tests and hillbillier-than-thou posturing. All country music is popular music in some measure; Hank Williams and the backbeat behind him was Nashville glitter compared to the rural music tumbling along in oral tradition in the days before mass media culture. That’s the point, more or less—country music, Shepard’s raw honky-tonk sound very much included, is what happens when the folk music of impoverished America gets an A&R department.

Okay, but. Country music needs characters, and the guardian of tradition is a pretty good character—especially if that guardian is as stubborn and spunky as Jean Shepard. (And she wasn’t wrong to fight; we don’t need to hang the DJ, but we do want to keep channels open for the old ways.)

In 2003, Us Weekly model Blake Shelton, on the heels of winning CMA Male Vocalist of the Year, said, “music has to evolve in order to survive. Nobody wants to listen to their grandpa’s music. And I don’t care how many of these old farts around Nashville going, ‘My God, that ain’t country!’ Well that's because you don’t buy records anymore, jackass.”

Shepard, as in today’s song, studiously avoided cursing in her reply: “We’ve got a young man in country music who has made some pretty dumb statements lately that traditional country music is for old farts and jack-you-know-whats. Well, I guess that makes me an old fart. I love country music. I won’t tell you what his name is—but his initials is BS—and he’s full of it!”

Zing! But the story that truly cracks me up is when Olivia Newton-John won the CMA Female Vocalist of the Year in 1974, and the old-school stars were so pissed that they formed a rival organization, with Shepard as president. Members included Dolly Parton, Roy Acuff, Conway Twitty, Porter Wagner, Johnny Paycheck, Mel Tillis, and various other legends. The first meeting was at George Jones and Tammy Wynette’s house, with their stated goal “to preserve the identity of country music as a separate and distinct form of entertainment.” I mean. Poor Olivia!

“She’s a very sweet lady, I’m sure,” Shepard said later. “But what she sang wasn’t country music.”

Notes and Marginalia:

If you dig Shepard, there’s a huge catalog to meander through, including “Second Fiddle to an Old Guitar,” “Sad Singin’ and Slow Ridin’,” “Twice the Lovin’ (in Half the Time),” “Many Happy Hangovers to You,” “My Wedding Ring,” “The Root of All Evil (Is a Man),” “Act Like a Married Man,” “Slippin’ Away,” and too many others to mention here. If you want to really immerse yourself in the heartbreak, her 1956 album Songs of a Love Affair, often cited as one of the first concept albums in country music, is a salt-of-the-earth melodrama as unrelenting as Scenes From a Marriage.

When Olivia Newton-John got the nod from the CMA, the other nominees she beat out were Loretta Lynn, Anne Murray, Dolly Parton, and Tanya Tucker. Yikes.

One evening in 1963, Shepard—then eight months pregnant—was at home giving her 15-month-old baby a bath in a big kitchen sink. Her husband, the country singer Hawkshaw Hawkins, was out of town, having just played a benefit concert in Kansas City with Patsy Cline and other stars. Standing over the sink, Shepard suddenly had a feeling of unease so intense come over her that she thought she might be going into labor. A couple hours later, she got a phone call: A plane carrying her husband, Patsy Cline, and Cowboy Copas had crashed in the woods near Camden, Tennessee, killing all three passengers along with the pilot. Here’s her telling of that night.

Shepard was finally inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2011 (outrageous that it took so long, a delay perhaps influenced by her ornery attitude toward the industry’s embrace of what she derided as pop country). At the awards ceremony, she spoke about breaking into country music in the early 1950s as a woman. “As you know, there wasn’t none of us,” she said. “But I was happy to do my part. I hung in there like a hair on a grilled cheese.”

Or rather “two whoops and a holler.”

Wilson was Husky’s uncle, and taught him to play guitar. Husky had written Shepard’s breakout hit, the million-selling “A Dear John Letter,” around this time—and at least according to the Second Hand Songs site, he would occasionally pen songs and then give the credit to his uncle Clyde.

Comrades, behold the development of honky-tonk angel consciousness: whereas Wells’s song laments “good girl[s]” who “go wrong,” Shepard’s announces that “the women ought to rule the world.”

Didn’t know this song till now. Thanks. Kitty Wells & Hank Thompson’s were on the playlist and this should have been!