Violet Hensley, 106, the Stradivarius of the Ozarks

Danger, death, fiddling, clogging. "Met a lot of people, done a lot of things."

In case you are having a dreary day, let me introduce you to Violet Hensley, the “Stradivarius of the Ozarks.” The fiddle maker was just a youngster, 96 years old, when this short film below was made by Joe York for the Historic Arkansas Museum’s Arkansas Living Treasures project. She is now 106, apparently still going strong and I believe still fiddling.

That bit just after the two-minute mark is one of my favorite snippets of documentary film ever. It’s a phenomenal twelve-minute piece, watch the whole thing! She learned to clog at age 69, by the way. She’s really something.

I got to meet Violet a few months shy of her hundredth birthday for an article I did for The National, the now-defunct in-train magazine for Amtrak. They had a good travel budget, which was nice, although in this case, it was just a seven-hour drive from Nashville to her home in the Ozarks, in Yellville, Arkansas. They paid for the gas.

I visited with Violet in her house (seen in the documentary) and she played some fiddle for me and told stories. From my story:

Sitting in her kitchen in Yellville, Arkansas, Violet Hensley tunes up a fiddle she made by hand in 1934. Hensley is 99 years old but you wouldn’t know it when her foot starts stomping out the beat and her bow starts flying. Her sight is mostly gone, but as her eye doctor told her, you don’t have to see to play the fiddle. “No, you don’t,” she tells me, before launching into “Black Eyed Susan,” gently singing as her fingers work along the neck.

Like all of the 73 fiddles she’s made, she refers to the instrument by number, in the order that she made them—the one she plays, her favorite, is Number 4. They’ve faded a bit with age, but you can still make out the hand drawings of wildflowers she made on the pine top and maple back when she built the instrument as a teenager, colored with red, green, and yellow crepe paper.

“I’ll be 100 years old on October 21,” she says. “I’ve met a lot of people, done a lot of things. I’ve been a barber, a blacksmith, a luthier, a farmer, and a logger—cut timber and skidded the logs out of the woods with a mule.” That’s not to mention touring the country playing music and demonstrating fiddle-making techniques, releasing three albums, being featured in National Geographic (the photographer was fascinated by the family’s pet skunks), and appearing on television shows like “The Beverly Hillbillies” (Hensley couldn’t pick up CBS at her house at the time and didn’t see the episode until years later) and “Regis and Kathy Lee” (she tried to teach Regis how to hold a fiddle—“Get it up under your chin, boy”).

That story is no longer online, so I thought it would be fun to do a little post celebrating Violet, one of the most energizing people I have ever met. Though I’d never seen news of it, I figured she must have passed by now. Nope. I emailed a bit with her daughter, who told me that Violet is still doing well.

On Facebook, Silver Dollar City—the amusement park in the Missouri Ozarks and a longtime spot for Violet performing and teaching—highlighted her joining their Homestead Pickers for a special performance last October just before her 106th birthday:

I mean!

The Facebook page on her that her family runs has frequent updates, including pictures from a fiddlers’ convention in Harrison that she attended last month. She seems at least as active as me, if I’m being honest.

Here’s more on Violet from my old story in The National:

Hensley is a legend in the old-time music community, known as the “Whittlin’ Fiddler” and the “Stradivarius of the Ozarks.” Her handmade fiddles are prized for their craftsmanship and unique sound. She’s given some to family members but most are now owned by collectors, aficionados, and museums—Number 14 was given to the late U.S. Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia.

The fiddles were made with hand tools at her kitchen-table workshop: pocket knives, hand saws, rim presses, hand planes, and homemade curved knives and bending jigs that her father invented—no machinery other than a drill press. Many feature beautifully designed horse heads at the top of the neck (when she was younger, Hensley broke and shod wild horses and rode bareback; in addition to making fiddles, she has whittled hundreds of animal sculptures and percussive wooden spoons).

It took Hensley around 250 hours to make each fiddle, whittling a five-gallon bucketful of shavings. Her vision is too poor to make a complete fiddle now, but she can still whittle by feel and continues to share her craft; this fall will mark her fiftieth year demonstrating her technique at Silver Dollar City, the Branson, Mo. theme park.

Hensley made her instruments from a variety of native Ozark woods, many cut down by Hensley herself. “Someone asked me a long time ago what my secret was of putting the tone into a fiddle,” she says. “The tone just comes in with the wood as best as I can figure.” She uses soft woods in the front and hard woods for the back, sides, and neck. “I’ve used buckeye, sassafras, pine, spruce, basswood, myrtle, cherry,” she says. “Curly maple, soft maple, bird’s eye maple, quilted maple, flamed maple, and just plain hard maple. I’ve used them all.”

Violet wrote a memoir in 2014, and it’s a treat (you can order it on her website). There’s amazing country DIY stories throughout, plus a chapter-length how-to guide to making fiddles, instructions for the games she played as a child in rural Arkansas, her personal notes on fiddle tunes, and so on.

And endless fantastic details from her life. Making soap, picking huckleberries, country doctors, log houses catching fire, making a broom from broomcorn, taking baths in a washtub by the cookstove or the fireplace, the tortoise she befriended watching her parents hoe corn when she was six years old. That was the same age she was put to work cutting grass and chopping cotton. “Violess, make yourself useful as well as ornamental,” her dad would tell her. Her father, a towering figure in her life, was five foot three, same height as her mama: “Dad use to say they could put a board across their heads and put a bucket of water on it and they could walk without spillin’ it.”

My copy is inscribed, “With best wishes to my new friend David Ramsey.” Picking it off the shelf today and flipping through at random from her depiction of the early days, Violet gifts us with sentences like this:

“The handyman of the community, Dad repaired sewing machines, plows, and fiddles.”

“My dad didn’t have no money in the bank, so the bank closures didn’t hit us. We didn’t have anything to do with no banks.”

“Adren [her eventual husband] was footloose at 15 because his mother, Savannah, had died of the flu.”

“We got married the last day of April 1935. He had three pennies in his pocket. Adren had to go the day before to Mount Ida to get our marriage license. It cost three dollars that he borrowed from Dad. We got Justice of the Peace to come over on a Tuesday. I ain’t sure if we paid him anything. For my weddin’ outfit, I had just made me a new yellow and pale green striped dress, and that is what I wore. Adren wore his plain overalls and blue-gray shirt. We stood in front of the fireplace that helped build just a few years before and took our vows. Our honeymoon began that afternoon by layin’ by the Irish taters. The next day, we plowed corn.”

“Adren made a bread pan out of a car door to just fit in the over. I made thirty-six biscuits three times a day because Adren wouldn’t eat cornbread.”

“I wasn’t in labor long—about four or five hours. I figure it was so short because I was in such good shape and had muscles like an ox. Before I got pregnant, I could put my right hand behind Adren’s knees and my left hand on his chest and flip him over my shoulder. I could wrestle him and throw him every time—and he was really tryin’. He later got strong after he went in the Army.”

And so on. Oh, and she raised nine kids, did I mention that?

Here’s more on her life story from my piece in The National:

Hensley grew up on a farm in Montgomery County, in western Arkansas. Her father was the handyman of the community and made fiddles in his spare time. “He’d sell one for a dollar, or trade one for a milk cow,” she says. “He traded one for a shotgun, traded one for a farm wagon.”

When she was fifteen, she told her father she wanted to make one. “I said, ‘shoot I can make one of them,’” Hensley recalls. “He said there’s the tools and the wood, just go at it.”

Teaching herself based on observing her father’s technique, she made four between 1932 and 1934. Then she got married at 18 and raised nine children. She didn’t make another fiddle for twenty-seven years.

“I didn’t really have time,” she says. “We made a garden and canned fruits and vegetables. I made all the clothes we wore. I gave all the shaves and haircuts, and I did that for the neighbors too. If I wanted a fence built, I built the fence. If I wanted a tree cut, I cut the tree.”

In 1961 she got the itch again and started making fiddles and playing square dances and craft shows, eventually earning a slot at Silver Dollar City when the folk music revival took off.

Along the way she added clog dancing to her repertoire. “I learned when I was 69 years old, because I saw some other people a doin’ it,” she says.

Hensley still seems tickled that folks are so interested in her fiddles. “I made one because I wanted to play one,” she says, no different than when she used to carve a wagon part she needed.

That photo of Violet up top is by Kat Wilson—do check out her wonderful “Habitat” series and other work. Here’s a public radio story where you can read more about Kat’s shoot of Violet.

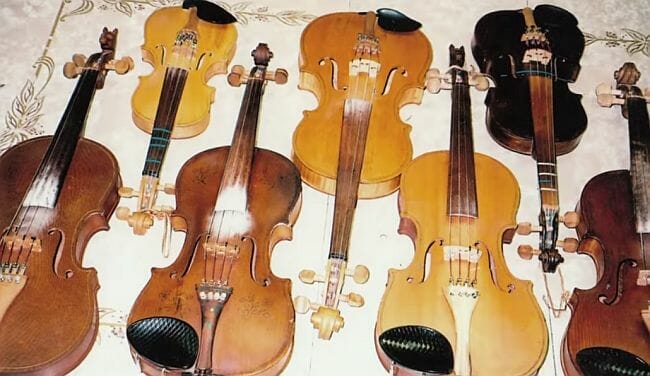

Here are some of the fiddles Violet has made. Not the horse head on a couple of the fiddle scrolls; the book has a photo of another with an ornate lion’s head she whittled.

For more Violet, here’s a 2007 story on her on CBS News, which includes footage from a great 1973 interview she did with Charles Kuralt:

And here’s a more recent story on PBS NewsHour.

See that? That’s danger. And you see this? That’s death.

“My life would be pretty dull without music,” Violet wrote in her memoir. On the one hand, I absolutely know she means. But I don’t quite believe it.

I really like your first article and this updated version as well! She is still spry, still walking, and loves people!

Love it. But how old is the daughter?