Ales Pushkin, the Belarusian artist and activist, died last July while incarcerated as a political prisoner. He was 57. Held in a prison in Grodno in western Belarus, he was apparently transferred to a medical unit, where he passed away. It’s natural to wonder exactly what happened. When his wife announced the news on Facebook, she wrote: “Tonight Ales Pushkin died in intensive care under unknown circumstances.”

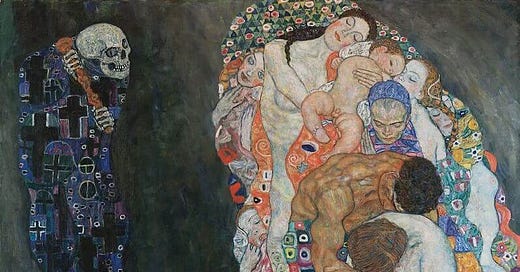

Pushkin’s dissident art work explored religious themes and often took sharp aim at the authoritarian leader of Belarus, Aleksandr G. Lukashenko. Even as many artists fled the country and Lukashenko’s rule, Pushkin stubbornly stayed home. He was playful and prankish. “Playing the holy fool is the highest form of freedom that’s ever existed at any time in our country,” he said.

From his obituary in the New York Times:

Mr. Pushkin was arrested multiple times over the years for acts of protest against the authorities, including through performance art pieces, which cheekily incorporated the legal process. “The police and the judge who administers the fine become part of the performance,” he once said.

Pushkin’s final arrest was in March 2021, charged with “rehabilitation of Nazism” because of a painting depicting a historical anti-Soviet resistance fighter. When reporters contacted him after his house was raided on March 29, he was working on a restoration at the nineteenth century Bulgakov Palace in Zhilichi. He was about to gild the entablature. He still had gold on his hands. The next day, he was arrested and detained in the palace chapel.

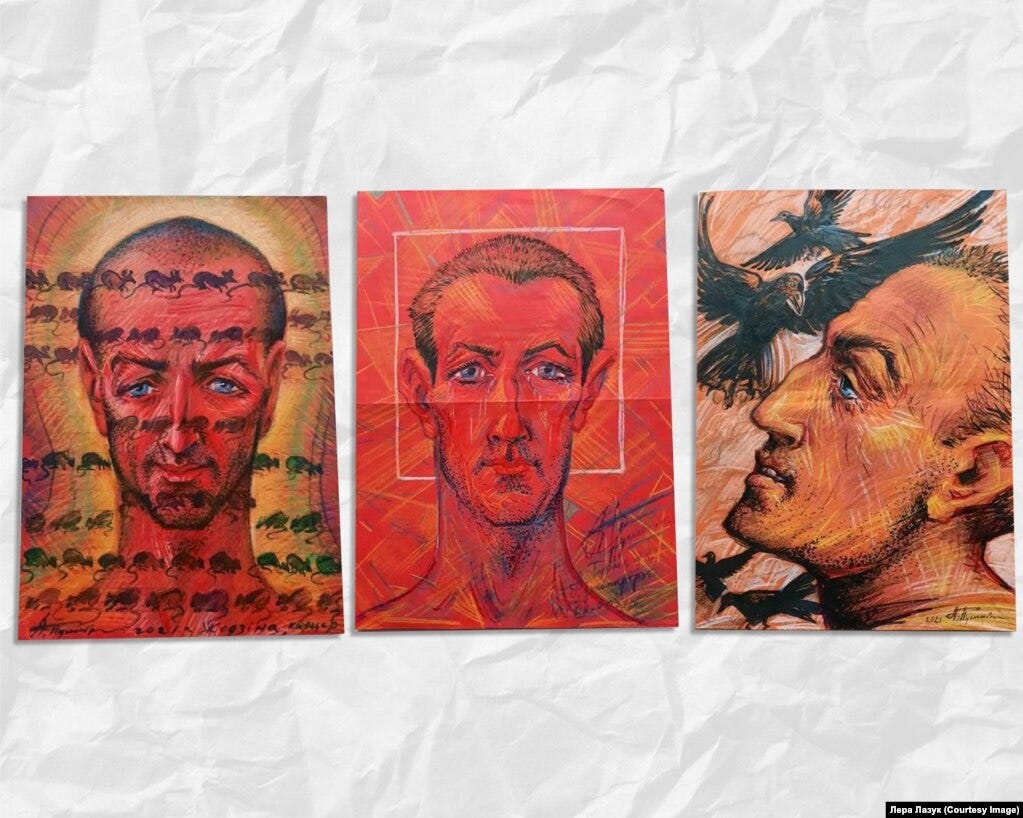

Via Radio Free Europe, here are some drawings he made while in prison:

This was the headline in AlJazeera after his death, which surely Pushkin would have loved:

“Belarus artist who put manure at Lukashenko’s office dies in jail.”

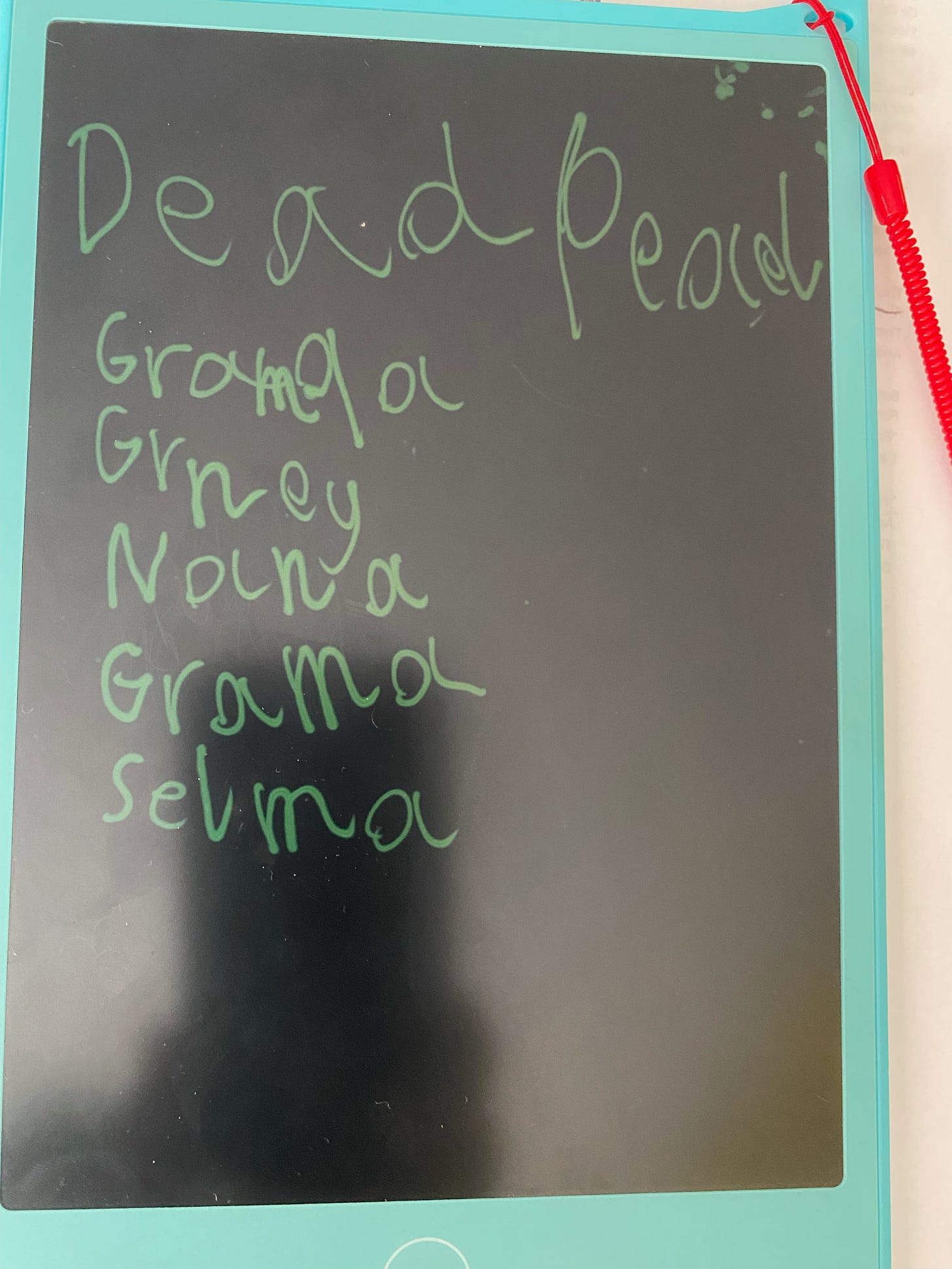

The other day my daughter handed this to me without comment:

“Anyone else?” she asked.

Catch-22 is a weird movie, but I have a soft spot for it. The book is such a razor in the zeitgeist, I get why someone would want to make it into a film—but its irony is so fixated on language that there is something inherently goofy about converting it into motion pictures.

You cannot avoid a highly stylized approach to adapting this book, and the crackle of dialogue has a winking feel, often sounding more like classic Hollywood than the grittier American films earning raves at the time, director Mike Nichols’ included.

For me, it’s Alan Arkin’s performance that makes the movie. His answer to the puzzle of how to channel Yossarian’s bite without Heller’s prose is what you might call slapstick anxiety. It’s there in the dips and gulps in his voice, it’s there in the way he moves his body. He is charming—Arkin always is—but at times comes across like a rag doll in trouble. And all of this is done at such a low hum. Even when he’s shouting, he never overwhelms the space. There was a sizzle to Arkin’s style, without a doubt, but he had a knack for understated angst. “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation,” as someone or another wrote. Arkin could show you the full weight of that in a few minutes on screen.

As we saw a couple decades later in Glengarry Glen Ross, Arkin’s great gift was to take bombastic dialogue from a writerly screenplay and make it humane. He could retain the crispiness of a hardboiled line while somehow—mysteriously to me—conveying the soft underbelly of a character’s fear and vulnerability.

Perusing his Wikipedia page after his death last June, I learned that he had been an occasional director as well. His first film was Little Murders in 1971.

I found it on YouTube, and boy, this is one of the strangest and freshest films I’ve seen in quite some time. Elliot Gould plays a nihilist photographer who takes pictures of poop. Like Arkin, Gould is charming in spite of himself, charisma seeping through his flat affect. But this is one of the most committed dramatic interpretations of nihilism I’ve ever seen. That sounds boring. But there is something emotionally stirring in the emotionless blank void. (Like there is a kind of sexless eroticism, and thrilling lack of action, and jokeless humor for much of the proceedings. It’s a weird film!) It has something to do, I think, with the chemistry (or anti-chemistry?) Gould has with Marcia Rodd, an actress I was unfamiliar with. She’s electric in this role as a snappy normie with a savior complex. She’s a crackling light in the film’s wacko darkness.

Oh, and then Donald Sutherland turns up as a preacher who’s more nihilistic still. His performance is buoyantly effortful, finding the joy in a character compressed with bullshit and ready to pop. He’s like a guru bottled in a whippet. And Arkin himself as a policeman having a nervous breakdown. This is all set in a fever-dream vision of New York City in a state of violent municipal collapse. Sort of Archie Bunker by way of Arthur Schopenhauer? Tones and moods and plot simmer in and out, a kind of aimless dream. Sometimes it’s a nightmare, sometimes it’s not.

The film is based on a play by Jules Feiffer (another Wikipedia page worth a rabbit hole or three), and it retains the look and feel of a play. But Arkin turns out to have a wonderful knack for color and framing. The movie pulses vividly in its own absurdity. There is something akin to the flow of John Cassavetes, but Cassavetes was always more invested in chatter than pictures (or faces than backdrops). Arkin has a painterly eye even in the cloistered spaces where the characters aimlessly thrash at themselves and each other.

I’m not going to say too much more about the particulars of what happens because I saw this movie having no idea how weird things were going to get, and you should, too.

In spite of itself, I think maybe it’s one of the best conservative movies I’ve ever seen. It’s not reactionary, exactly, but it’s a kind of piercing critique of the counterculture from within a countercultural filmic language—a bit like the very different The Great Beauty. But this is 1971, so it all feels more personal, the stakes all feel more immediate, the die has not yet been cast—or it has, but they didn’t know it yet. I think this is part of the weirdness, the way it has all the trappings and textures of an amoral riff, but keeps recentering around a kind of decency. So that the riffing feels ever more askew, ever more disorienting, ever more nauseating. Until we get to the sharp turn in the final fifteen minutes or so, which—well, just watch it. Is the film a celebration of meaninglessness or a scathing critique of the decadence of a society shredding any shred of tradition? Or both?

What a picture. It’s really something.

One thing, unmentioned at her funeral but important to me: Grace’s grandmother kept driving herself to dances until the very end.

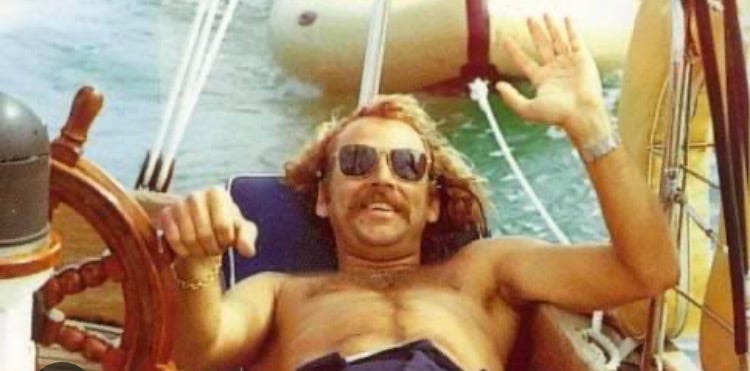

Perhaps not since Achilles has a man walked the Earth who was so committed to his own vibe.

Do you ever read the obituaries, just as a way to read stories about people you never knew? There is something textured about the form that I like. They are typically unremarkable. But that depends on your definition of remarkable. I read one not long ago about a woman who had been working as a dental hygienist. She started chatting with a patient one day. She married him. All kinds of stuff happened after that, most of it unmentioned in the obituary. But this much is recorded in the annals: “Her home was always open to family and friends. She enjoyed entertaining, playing bridge, traveling, the family lake house, Sunday night dinners with her family, and an evening stroll around the neighborhood.” A well-lived life, see.

She would have liked to tell them that behind Communism, Fascism, behind all occupations and invasions lurks a more basic, pervasive evil and that the image of that evil was a parade of people marching by with raised fists and shouting identical syllables in unison.

—The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera

In times when history still moved slowly, events were few and far between and easily committed to memory. They formed a commonly accepted backdrop for thrilling scenes of adventure in private life. Nowadays, history moves at a brisk clip. A historical event, though soon forgotten, sparkles the morning after with the dew of novelty. No longer a backdrop, it is now the adventure itself, an adventure enacted before the backdrop of the commonly accepted banality of private life.

—The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Milan Kundera

A Tropical Depression reader sent along this beautiful American paragraph from an obituary of a singer of some renown who passed away not long ago:

Anthony Dominick Benedetto was born on Aug. 3, 1926, in the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens, and grew up in that borough in working-class Astoria. His father, Giovanni, had emigrated from Calabria, in southern Italy, at age 11. His mother, Anna (Suraci) Benedetto, was born in New York in 1899, having made the sea journey from Italy in the womb. Their marriage was arranged. Giovanni and Anna were cousins; their mothers were sisters.

One of a kind. Rest in peace, or in power, or whatever you might seek.

Loved this one.

I somehow came across a trailer for Little Murders about a year ago and was intrigued; I could make zero sense of what it was about based on the bizarre imagery of the trailer. But I didn’t seek it out. I will!

Minor typo: spelling of Schopenhauer :)

I think this is the best writing I read these days. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you for death and politics and very weird films. Thank you for quoting Kundera. For me that's where all of writing began. Thank you for the feeling of an excellent conversation with a brilliant friend.