The Teething Review

Children's Book Reviews, Vol. 1: Amos & Boris by William Steig

Amos and Boris (1971), 28 pp.

William Steig

Rating: 10.0

There is a kind of hyper-vivid déjà vu that happens periodically as a parent. It keeps happening, but I am specifically referring to a confounding version that occurs most intensely when your child is in the first two to three years, say. Or at least it happens to me.

Déjà vu might not be the right word. It’s not that I feel I am re-experiencing something, it’s that a forgotten experience of my own suddenly surfaces in my child. And I can feel it, both in my child in the moment and as my own in the past. The example that comes to mind is that when my daughter had temper tantrums, I would suddenly have access to my own private, lost, subjective experience of having a temper tantrum when I was a toddler. Not that I would have a temper tantrum in that moment, as an adult parent. Just that the immediacy and pain and meaning of that emotional mode suddenly snapped into being for me, like I time-travelled into my childhood consciousness and got a peek—immersive, clear, and in focus.

It’s uncanny. Then this other uncanny thing happens at the same time. I start re-experiencing something that I never experienced in the first place: the perspective of my own parents when I was a child. The lens works both ways. I can reckon my self as a child having a tantrum, and now I can newly reckon my parents witnessing the tantrum.

A simpler example—when my daughter gently runs her finger over the hair on my arms, I am experiencing that at the same time as I experience doing the exact same as a child to my own father. I am myself in both places, both times, at once—and then find that I am simultaneously also experiencing it as the father back then and the child right now. It’s disorienting.

I can at least testify that I’m not alone here. My friend Mike Powell wrote about this some years back. He described the phenomenon as “sensations too vague to call memory but too specific to call empathy…the confluence is enough to make me feel like I have fallen backward through my own life, somehow my son and my dad at the same time.” Yes, that’s it.

A quieter trigger for this feeling is reading to my children. Particularly when I am reading books that were favorites—or forgotten favorites—of mine when I was a kid and my parents were reading to me. My parents never threw anything away, so we wound up inheriting the best of the bunch. Which means that in many cases I am reading literally the same physical book that was read to me as a child. Spooky action.

Amos & Boris was one of these books we inherited from my parents. The first time I read it to my daughter, the cover was familiar to me right away and the look of the illustrations immediately tickled cozy old memories. I knew it had been read to me and that I liked it. But whatever memories I had needed nudging—I wouldn’t have recalled it at all if we didn’t have the physical copy. It was maybe conflated in my mind with Abel’s Island, also by William Steig, and also involving a clever, nautical mouse (also excellent). That was a chapter book and I would have read it later. I had at least vague memories of that, whereas with Amos & Boris, I just had a contentless notion that it was a classic of my childhood.

And so I opened the book and started reading to my daughter. The book is about a mouse who seeks adventure at sea, runs into trouble, gets aided on a journey home by a whale, and later finds a way to return the favor. That’s pretty much the story. But y’all. It is so rich, so unhurried, so loving, and so casually wise.

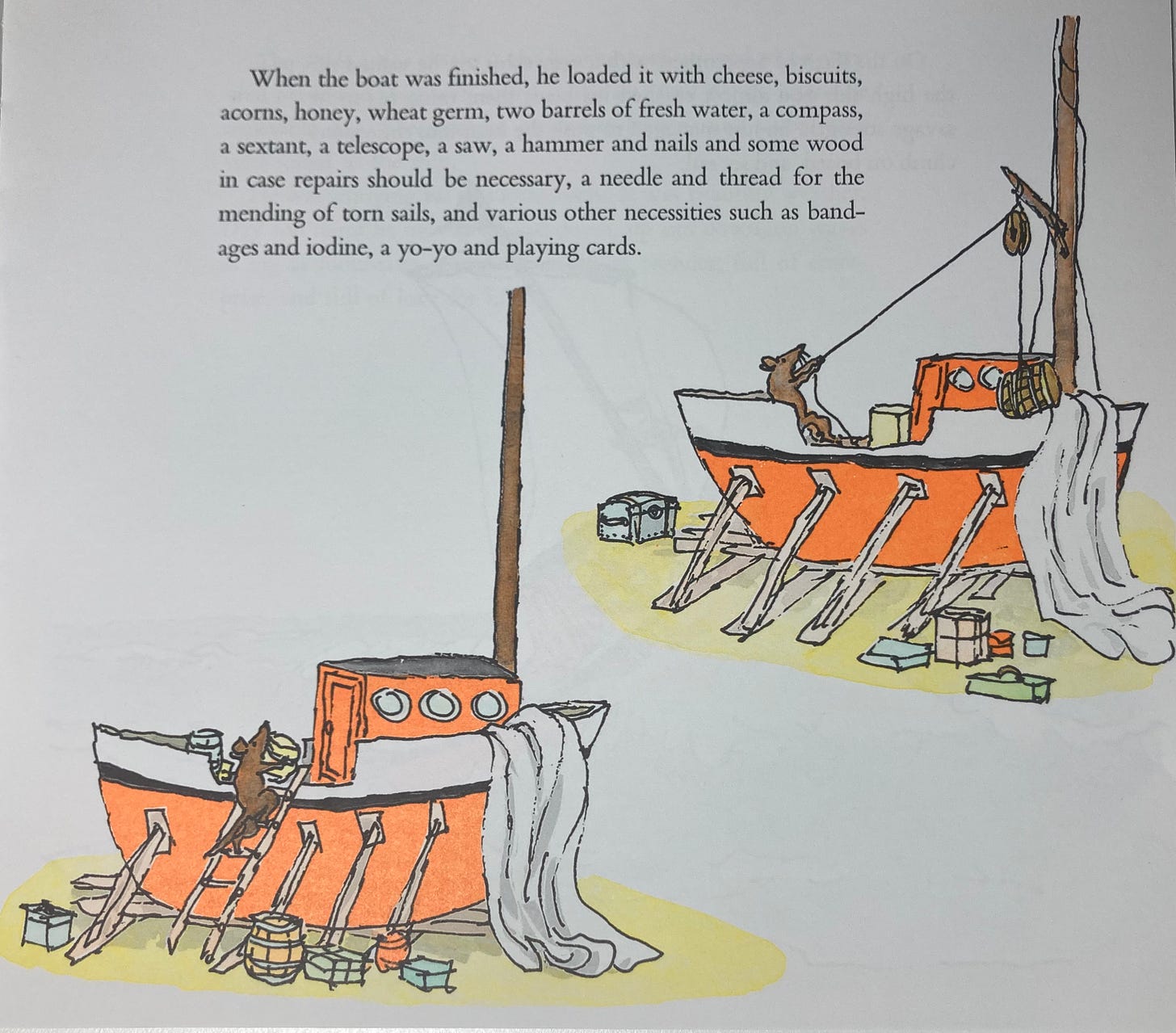

The details are exquisite. Amos the mouse builds his boat by day and studies navigation at night; when the boat is finished, he loads it with the following:

cheese, biscuits, acorns, honey, wheat germ, two barrels of fresh water, a compass, a sextant, a telescope, a saw, a hammer and nails and some wood in case repairs should be necessary, a needle and thread for the mending of torn sails, and various other necessities such as bandages and iodine, a yo-yo and playing cards

As I read on, it became clear to me that the manner and mode of this book was arguably one of the single biggest influences in my life on my own writing and creative instincts. I don’t know how this seeped through, or how to think about the anxiety of an influence you didn’t even remember. I just know that once I saw it, it was clear. This had been knocking about in me for a very long time.

Here’s a passage I love:

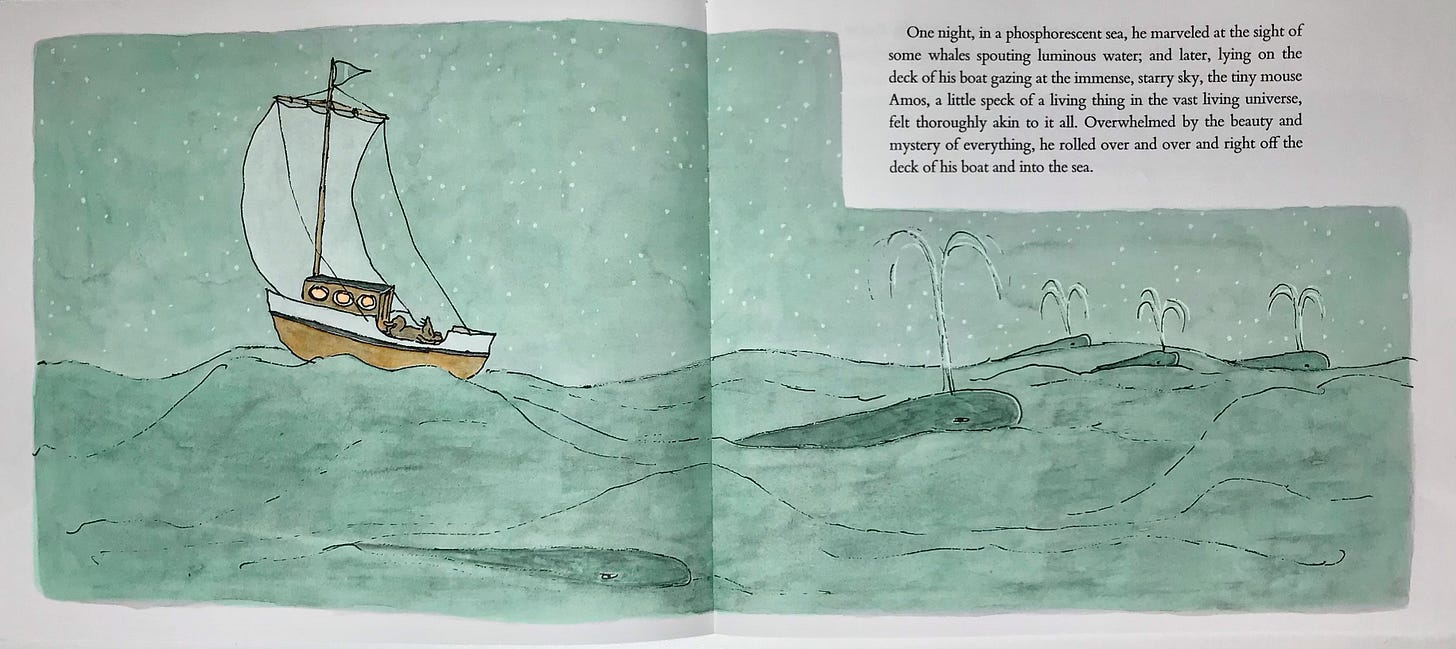

One night, in a phosphorescent sea, he marveled at the sight of some whales spouting luminous water; and later, lying on the deck of his boat gazing at the immense, starry sky, the tiny mouse Amos, a little speck of a living thing in the vast living universe, felt thoroughly akin to it all. Overwhelmed by the beauty and mystery of everything, he rolled over and over and right off the dock of his boat and into the sea.

I will never write such a perfect paragraph of cosmic slapstick, but this is something like my North Star, a toy allegory not just for the way I tell a story and the way I hope to write, but possibly also for my personality and worldview. Feeling so thoroughly akin to it all that I don’t realize I’m falling right off the boat.

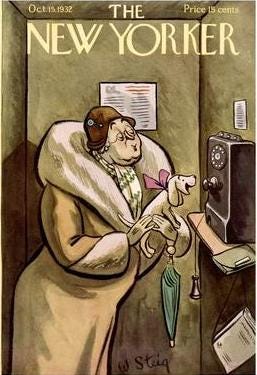

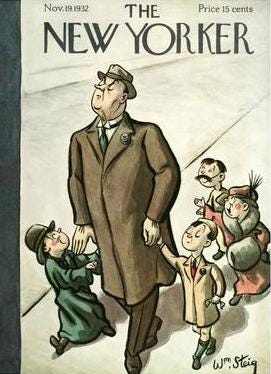

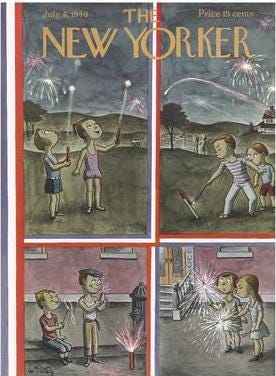

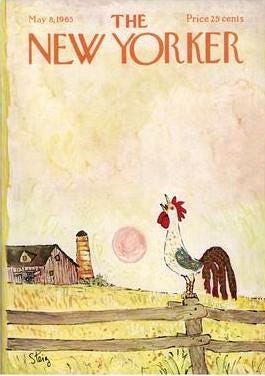

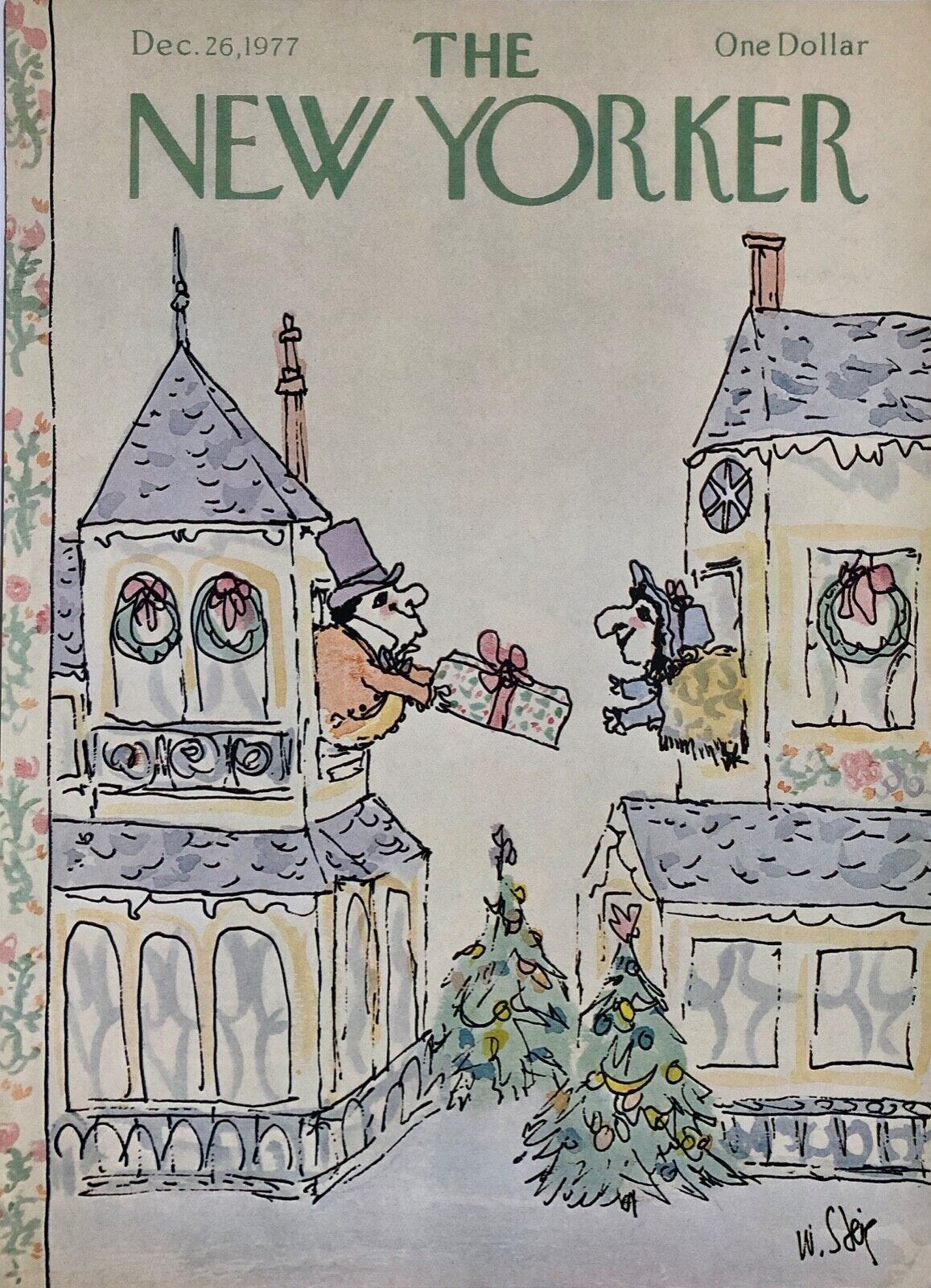

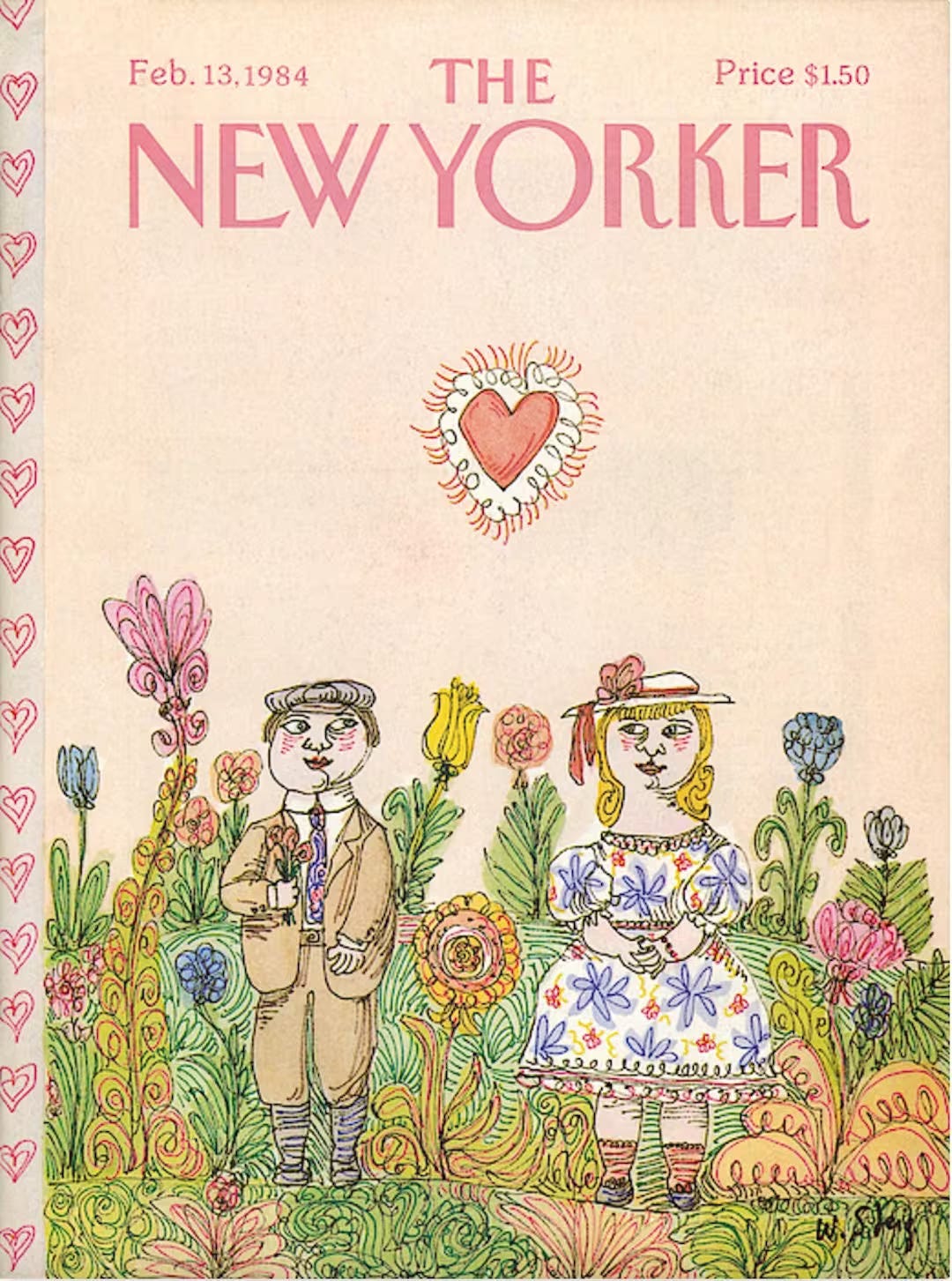

William Steig began as a cartoonist for the New Yorker in 1930 when he was about twenty-two years old and continued contributing there until he died in 2003. At the time of his death, he had published 1,675 drawings for the magazine and 121 covers, with yet more drawings published posthumously. Roger Angell, who had previously written a long feature on Steig, wrote his obituary for the magazine, recounting that “[h]is first cartoons here called upon his beginnings in the Bronx—he was the son of socialist immigrants; his father was a housepainter—and found comedy in families living in cramped apartments with kids underfoot and a trickle of air or springtime coming in over the fire escape.” But his grace with line and color—versatile and playful—saw him quickly expanding his range. Here’s a few samples of his covers (you can see his style evolve over time):

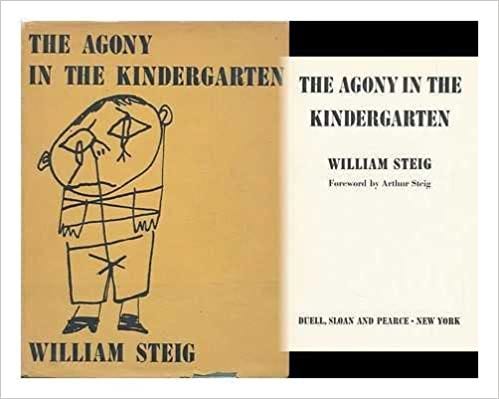

Between 1932 and 1963, he published a good number of collections and short, illustrated books for adults. I haven’t yet tracked these down, but I’m very intrigued. The titles are promising: The Rejected Lovers, Persistent Faces, The Lonely Ones, All Embarrassed, About People: A book of symbolical drawings, and so on.

Or this one, which reviews on Amazon praise but loudly warn is not a children’s book:

He also illustrated books for humorist Will Cuppy and a couple of books on poker penned by his brother, a journalist and painter. He had a very interesting life and I am skipping some details, like the box he would enclose himself in daily in order to accumulate a healing organic-cosmic energy—a theoretical life force deeply channeled in organisms and orgasms.

In 1968, he made the move to children’s books, which he continued to publish at a clip of about one per year for the rest of his life. The first one, CDB!, is written in code using gramograms (letters that can signify words, like you might do in a text message today—CU for “see you,” for example). The illustrations, at that point still in a style reminiscent of New Yorker cartoons, help you figure out the puzzle on each page, but they can be pretty hard. It starts easy: “CDB” has kids pointing at a bee, so that’s “see the bee.” But later you get: K-T S X-M-N-N D N-6, which translates to “Katie is examining the insects.” These little language riddles go on for 47 pages (in later editions he added an answer key at the end). Again, this was his first children’s book. What a guy.

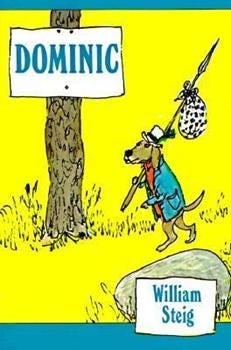

In 1969, he earned a permanent place in the children’s lit pantheon with the classic Sylvester and the Magic Pebble; in 1990, he published the wonderful Shrek!, which presumably eventually made him very rich. I’ve probably only even laid eyes on about a third of his children’s books, but everything I’ve read has been outstanding. Dominic, a chapter book, is an absolute masterpiece. Like Abel’s Island and Amos & Boris, it’s an adventure for the sake of adventure—this time starring a dog—with existential themes and cosmic flights of fancy. It also has this particular charm in lieu of the normal didactic lessons in children’s books. Steig’s works have an ethics, there is a moral code, but it reminds me more of the folk philosophy of Charles Portis than the lectures of the Berenstain Bears. Like Portis, they have a satirical bite, poking fun at these well-worn codes of behavior even as they clearly value them and hold them tight.

Dominic is a dog steadfastly committed to his unworried vision of the good life. He plays the piccolo and vanquishes criminal gangs. He loves to wander out and see what there is to see. He closely guards his freedom, needing nothing more than his “God-given nose to guide [him] through life.” We learn that “he had tender feelings for young ones of any sort, even for the babies of snakes, a species he otherwise regarded with disfavor.” He wears an assortment of hats, “not for warmth or for shade or to shield him from rain, but for their various effects—rakish, dashing, solemn, or martial.”

Angell recounts a story about a visitor to Steig’s home in Boston toward the end of his life. The visitor mentioned the beautiful view of the quaint Back Bay neighborhood. Steig said he missed his old second-floor apartment in the Village and all of the dogs and people and cars that passed by. “God damn,” he said, “how can you be happy in a place where the windows look out on nothing?”

Like the prose, the ink-and-water illustrations in Amos & Boris have a breezy quality, perhaps befitting a cartoonist used to working on deadline. They have the feel of being dashed off at the moment of inspiration. They are beautiful but they are not thirsty for your attention. In many of the images, most of the space is taken up by sand or sea or sky. For me there is something nourishing about their quiet restraint. They do not seek to show wonder, but to imply it.

I had no idea what Steig’s process was before reading the New Yorker obit, but Angell reports that this dashed-off quality was by design: “On a tip from his son Jeremy, a jazz flautist, in the sixties, he had stopped working from sketches and would wait, pen in hand at his drawing board, to act on whatever idea or style came next.” In Amos & Boris, there is something lively and alive in the line of his pen, simple drawings that are somehow imbued with the energy of change and renewal.

Let me now introduce the whale who rescues Amos after he falls into the vast sea and faces two illustrated pages of fear and loneliness as he flatly contemplates death. (I don’t think spoilers matter too much with an existential excursion like this, and also the book is only 28 pages long.) Boris saves Amos and takes a detour from a conference he has to attend at the Ivory Coast of Africa to take Amos back home. Boris has never encountered a mouse. He is motivated to make the detour because he is so intrigued by the chance to get to know a creature as strange as Amos.

The book has hardly any real scenes but tidily manages to convey the rhythms of the close friendship that develops over their journey. This is a buddy picture. Steig is luxurious in his description of the sweetness of their companionship, the energizing jolt of their otherness. His writing on their affection for each other is so charged that some might call it erotic. That’s not my read, or at least I don’t think the deep bond being described has anything to do with romance or sex. Instead, I’m put in mind of C.S. Lewis’s writing on the peculiar freedom and whimsy only possible in the love between friends, outside of romance or family:

I have no duty to be anyone’s Friend and no man in the world has a duty to be mine. No claims, no shadow of necessity. Friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself (for God did not need to create). It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival.

Here’s Amos & Boris:

Swimming along, sometimes at great speed, sometimes slowly and leisurely, sometimes resting and exchanging ideas, sometimes stopping to sleep, it took them a week to reach Amos’s home shore. During that time, they developed a deep admiration for one another. Boris admired the delicacy, the quivering daintiness, the light touch, the small voice, the gemlike radiance of the mouse. Amos admired the bulk, the grandeur, the power, the purpose, the rich voice, and the abounding friendliness of the whale.

They dig each other! I love how unafraid Steig is here about the intensity of friendship. That’s something that children know really well, sometimes better than adults, but the edges get shaved off in books for kids. Also: Exchanging ideas! Amazing.

Boris delivers Amos safely home. They are likely to never see each other again, after this wild journey, because Boris must return to the sea and Amos must live on land. It’s just the way of things. There’s another important plot turn at the end, but one of my favorite moments is the simple ease of their parting:

Boris…went back to a life of whaling about, while Amos returned to his life of mousing around. And they were both happy.

Amos & Boris has the force of fable but the easy breadth of an existential lark. It’s funny. There is something boozy and baggy about the storytelling style. (See the influence on yours truly?) It is urbane and witty. Streetsmart and full of wonder. And decent. Once upon a time, the ancients told stories around a fire, and the best ones were simple and rambling and true. And they were told again, and whittled down in spots and complicated in others and they came to be written down and we came to know them. But at first they were just stories. Amos & Boris is like that. Simple and rambling and true.

My whole family fell in love with this book. Another iteration: I believe my whole family also fell in love with this book when I was a child. But here I can’t be sure. My mother has only vague recollections of it. I think my father might have had a clearer memory—I don’t trust myself, but it seems to me that he was especially fond of Abel’s Island and I bet he had a soft spot for this one, too. He had a good memory for this kind of thing. But that’s one of many things I somehow never got around to asking him, and he passed away last September.

My daughter is five now; we probably started reading it to her when she was around two, after we had found it in a box from my parents’ old house. We were so smitten that we sent a copy to Mike Powell and his family. That’s the friend I mentioned above. They had their second kid by then, which was still in the future for us. We thought the book would tickle them in the same way it tickled us. I think we were right—I think they loved it. But maybe I’m remembering wrong. That’s exactly the sort of detail that gets lost in the haze of other details for me since I’ve had children.

For me especially, there was a particular reason I thought of Mikey, which is that the rhythm of Amos and Boris has some of the flavor of our chats over the years. These chats have become less frequent once we became fathers, but they feel ever more important. Dadas of the world, listen: You need compatriots. I don’t mean the dads you meet at the playground. I mean the deep confederates that you can discuss the contours of déjà vu with. Or whatever your thing is.

I’ve known Mikey for more than twenty years, though we’ve never lived in the same city. You know how it is: whaling about, mousing around. We try to keep in touch, coordinate and schedule, miss a few months, and fall right back in. Our conversations are half-baked and excitable. Swimming along, sometimes at great speed, sometimes slowly and leisurely, sometimes resting and exchanging ideas, sometimes… The other day he sent me a picture of a long row of academic journals at the university library. Yesterday I sent him a picture of Leonard Cohen playing pinball. We are smarter and brighter, when we get rolling together, and also sillier and dumber. We circle every notion until it sparkles and expires.

I like it when a conversation feels both beautiful and hard to hold. Like chasing dandelion seeds. But there’s something else to consider, and I like this about our conversations, too. If we are chasing dandelion seeds, I think Mikey would point out, or maybe I would, that if you pull back in the frame, you can see us from another point of view: A couple of fools with unwieldy nets, bumbling through a field—grasping after tiny, flittering seeds in the wind that only fly away for good, right through the holes in our nets. The image would be even funnier if we were talking animals. But I guess we are.

Find you a whale, mice. Find you a mouse, whales. Take your boat out to sea. Ask for help when you need it. Exchange ideas. Stare at the stars. Savor your acorns and honey. These vivid moments will soon belong to someone else as vague memories.

This morning my son had a blowout (poop that leaked out of his diaper). Enough escaped that a puddle formed around him. He likes textures. Before I could whisk him away, he was able to explore this organic matter that arrived like a gift. As I carried him by the waist toward the changing station, he clapped his poopy hands.

This afternoon, I read Amos & Boris to him for the first time. He turns one in a couple weeks. He pointed and slapped at the pages. He gently ran his fingers along the hairs on my arm. Amos and Boris made their journey. My son made grunt-squeal noises and gibberish syllables to let me know he understood—the very same sounds he makes to let me know he doesn’t understand at all.

Read aloud to my family and cried through the last third. I’d love to ramble with you sometime soon.

I have a book that belonged to my dad called Peter Church Mouse. There's a drawing of the antagonist, Parson Porridge jumping in the air as he finds yet another mouse-chewed church thing. His legs are kicked out in chubby splits, and his coat tail is dangling at just the right length and placement to give four year old me the best poop penis kind of excitement. When I read it to Rexina, the only thing she has eyes for is that man who poops in the air.