Right down with the people

The Phipps Family and the evolution of early country music (Part One)

This article was made possible via generous support from the Berea Sound Archives Fellowship Program. Special thanks to sound archivist Harry Rice, who brought me a stack of vinyl it would have taken me who knows how long to track down on my own. A small portion of this piece was previously published, in different form, in my Honky-Tonk Weekly piece on Roba Stanley.

My research at the Berea College sound archives, conducted over the last six months, has focused on the interaction between rural folk music and mass media, beginning in the 1920s and 1930s—the cultural brew that led to what we now call country music. The Phipps Family, from southeastern Kentucky, has often been derided in the literature on the history of country music as mere copycats. But for my purposes, they represent a fascinating case study. They grew up with the music of oral tradition, which they revere, but made their names with the entrepreneurial gambit to recreate an old-time sound that became popular—and you might even say passed into a new form of “tradition”—on record. I’ll also argue that their music is more interesting and varied than it has been given credit for.

There’s a lot of ground to cover, so I’m going to divide this into three parts. The second part will be published later this month.

Been back yonder

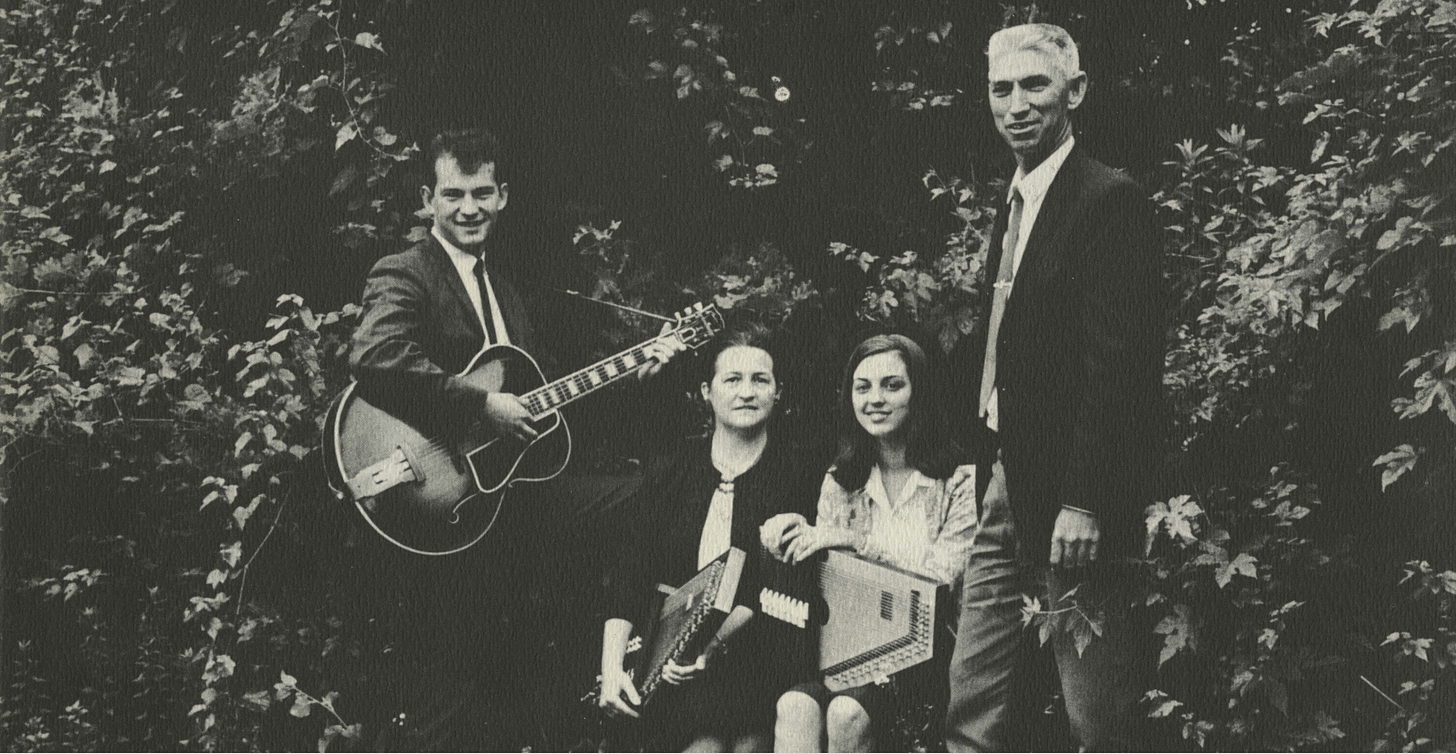

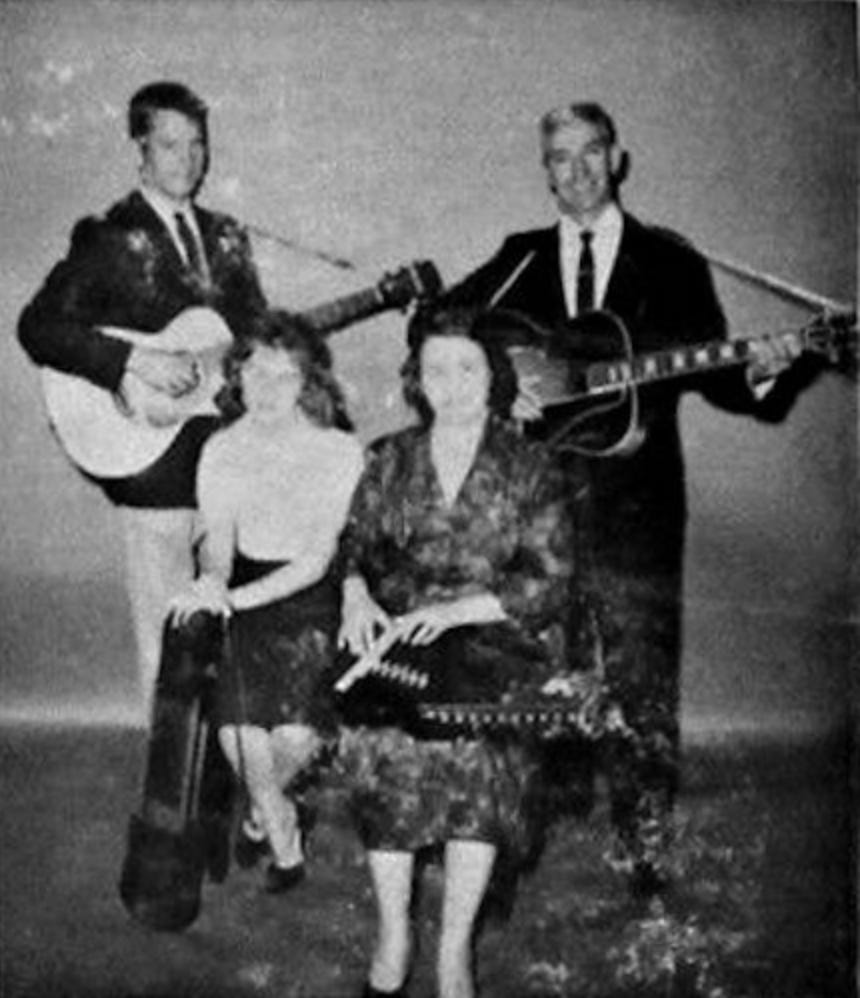

In 1993, A.L. Phipps of Barbourville, Kentucky, sat down for interviews with Harry Rice, the sound archivist at Berea College.1 Phipps was the patriarch of his family band—the Phipps Family, masters of traditional Appalachian music and a footnote in the history of early country music.

Speaking with an archivist perhaps put Phipps in a wistful mood, lamenting the songs and wisdom lost to history. “If they don’t get it from people like me that been back yonder in the early twenties, the music will get away,” he told Rice.

He regretted that he had not done more to preserve the old folkways as the rural South’s oral tradition fizzled out in the wake of mass culture: “Boy, I wish I would have took time. I could have got a world of history—of my kinfolks, of family history, family tree, not only that but a world of things in music. The people in the early music could have told me things that… But now they’re gone. They’re dead and gone. History’s gone. When they die, history dies and if you don’t get it before that, you just don’t. It’s lost.”

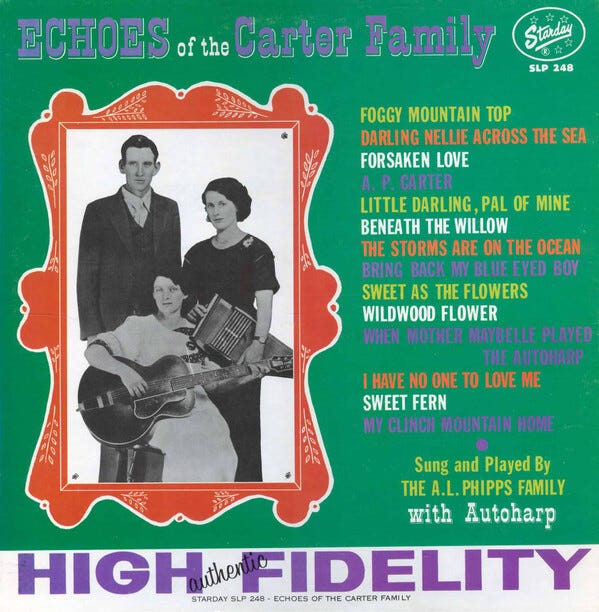

There’s an irony to Phipps’ nostalgia. The Phipps Family was best known for their knack for replicating the sound of the Carter Family. As they proclaimed on their 1963 album Echoes of the Carter Family, the Phipps Family developed a “style utilizing the same instruments and basic presentation that proved so popular for the Carter Family.” Released not long after A.P. Carter passed away, they promised that “the memory of his music is being perpetuated by the A.L. Phipps Family of Kentucky.”

Certainly, the Carter Family were in some sense clearly keepers of tradition. They were song catchers themselves: Much of their repertoire was comprised of traditional songs collected by A.P. Carter and his collaborator Lesley Riddle2 on excursions to farms and factories and coal mines; out in the country to hollers, valleys, and front porches; and to boardinghouses, street corners, or wherever else they could find folk songs they could make into their own.3

And the Carters became popular to people like A.L. Phipps and his wife Kathleen, who grew up listening to their records, because of their adherence to the old-time sound that had grown out of an oral folk tradition in the rural South. “The Carter Family music was the kind of music that was right down on a level with the people,” Phipps said. “Right down with the people.”

But the Carter family—and the mastery of much of their recorded repertoire by the Phipps Family in order to establish their own side career as professional musicians—also represented something very new.

Phipps grew up in a household of singers, and that family tradition likely extends back as long as the Phipps clan has been in Barbourville—dating to 1830 when his great-grandfather Jacob Phipps made the trek from southeast Virginia to build a log house by Stone Coal Branch. For the generations prior to A.L. Phipps, singing was part of a genuine, living oral tradition. For most people living in small rural communities, singing and playing music was something you did for people you knew. If you enjoyed listening to songs, the person singing was likewise typically someone you knew. You might learn songs from your mother singing while she did the chores or at a gathering on someone’s porch.4

That also meant that the songs were malleable, subject to change over time. I wrote about this phenomenon in a 2023 story on murder ballads in the Oxford American:

Oral traditions were chaotic, unfixed, unwieldy—stories forever in revision, never complete. Versions would branch without end, and older branches would be lost with time. How did the lyrics go? Well, that would depend. You could say a song existed in superposition, until someone sang it in their particular way.

Here’s A.L. Phipps recollecting how this played out when he was a youngster:

Everybody done their own thing back in them days. They didn’t pay much attention what the other feller done down the valley down yonder. They played and sung how they learned that song. And if the other guy had it differently, that was all right with them—they was going to sing it the way they learned it in their valley.

But this world—the world A.L. and Kathleen grew up with as children in Knox County—all of this was about to change.

The advent of radio and growth of affordable record players meant that you could listen to music in the home beyond what someone in your family might play—and new types of music, too, as the country’s local folkways now had the means to spread to mass audiences. The phonograph was invented in 1877, but it was slow to catch on for most Americans; in the first two decades of the twentieth century, sheet music still substantially outsold records. But by the turn of the century, record sales began growing rapidly. In 1900, around four million records were sold; in 1910, sales were nearly 30 million. By 1920, annual record sales were more than 100 million. Over those two decades, record players became common in the home, even for many lower-income families, who had affordable options available for the first time. Radio was also reaching more Americans; by 1929, one in three homes in the U.S. had a radio.

As this new way of experiencing music became more popular, listeners increasingly wanted to hear the particular version of a song fixed in wax. There was a new kind of interest in hearing the Carter Family song they loved rather than some other version in this valley or that one. All of this represented a revolutionary cultural change in rural communities.

Talent scouts like Ralph Peer of Okeh Records (later Victor) started showing up in these communities to locate musicians and record them in makeshift studios. These artists (a word that would have been utterly foreign to them at the time) were not professional musicians. Music was rarely a vocation in the rural South, it was a communal activity.5 Peer promised real money, which sounded great, but probably a little strange.

Keep in mind: When Ralph Peer recorded what is often labeled the first country music record—Fiddlin’ John Carson’s “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane”—the term “country music” did not yet exist. Even the term “hillbilly music,” which Peer claimed as his idea,6 was not coined until the following year.

But whatever country music might mean, this was its dawn: rural folk music’s encounter with mass media. This was the beginning.

But it was also the beginning of the end of the old-time folk traditions that Phipps reveres with such nostalgia.

By the time Phipps died in 1995, the music of the folk—the songs that chiefly belonged to the communities in which they were shared—had morphed into a mass-culture behemoth and a multi-billion dollar industry. The lives and musical careers of A.L. Phipps, his wife Kathleen, and their family band, give a glimpse of the ingenuity and tensions of rural musicians navigating these tectonic changes.

Seems to me like everybody could sing back them days

A.L. Phipps’s father, James Phipps, was a Baptist minister and a coal miner. He was also a singing school teacher in the shape note tradition, and made sure that his family was familiar with the shape-note system of reading music. He wrote the shapes and names of the notes in chalk across the arch of the family’s fireplace. “I learned those notes just from the shape, just looking at them,” A.L. said.7

Shape note singing, which used a simple system attaching shapes to noteheads, became a popular method for churches in the nineteenth century, particularly in the South. Itinerant teachers (initially from New England) came to the frontier to evangelize their method, teaching impromptu “singing schools” in churches or other gathering places in rural communities.

Shape note songbooks were designed to help people singing together in groups with pitch, and aid them in learning to sight-read music. (The Sacred Harp by B. F. White, published in 1844, was the most famous shape note hymnal; shape-note singing is sometimes called “sacred harp.”)

For Phipps and his community, singing together was in large part grounded in the church, where the singing schools were a major influence:

I don’t understand why…but seems like so many people now can’t sing, or don’t know music, or how to read it. … Course, I think one reason is back them days, we had church services and we had singing schools in those churches.

A guy would come along…it’s funny, he didn’t charge for nothing back then. Everything was free. He’d say, ‘Well I’m going to teach a whole week’s singing school here. You people come out, and I’ll learn you how to sing. I’ll learn you the rudiments of music, I’ll learn you the notes, I’ll learn you how to read this music, and it won’t cost you nothing.’ Most of the time he’d just could stand around among the neighbors that week though, and they would furnish him a place to sleep, and food. And that was it.

The songbooks and singing schools were part of a reform movement that first arose in the first half of the nineteenth century to replace what became known as the Old Way of singing—a style rooted in English parish churches that had predominated in the American Colonies. The Old Way involved no training, no musical notation, and no conductor, typically relying on “lining out” to establish the words and melody for the congregation. Some religious elites thought the singing that resulted was unlovely and disorderly (based on the language in their critiques, they seem to have also been worried that the Old Way represented a defiant populism in low-church Dissenters). The singing schools offered a very efficient system for musical education, helping eager singers without experience develop a more refined style, which became known as Regular Singing.

While most people today think of shape note singing (or “Sacred Harp”) as an old-time tradition, when it spread through the South, some rejected the diatonic formalism as an intrusion from outside elites on traditional practices (the Old Regular Baptists, for example, condemned what they called “note books”).

But for those open to the concept, shape note singing brought an ingredient to rural low-church music that the Old Regulars eschewed: harmony. Churches learning the shape note style would divide members into soprano, alto, tenor, and bass singers and form a square, another way of helping singers to keep on pitch by following others on their side of the square.

The periodic music education sessions from traveling teachers worked, Phipps said, leading to astonishing performances in rural Southern churches.

It was for anybody would want to learn to sing. The [singing school teacher], most of the time, could sing all the parts of music. He’d start out soprano, he’d get with the people that are on soprano, and then he would go right back to the next group. …. He taught all four parts. Bass, he could do it all. And by the time week was out, most of the time he had one of the finest singing quartets that you ever heard. I mean, they could all read music, and man, it would raise the hair right off your head, a whole group of people like that in a church, you know. Before that, they didn’t know how to sing. But now, buddy, he put them rudiments of music right there on a board or an oil cloth, whatever it might be—and they learned it. … We could order a new song book, and in a few days we had a bunch of new songs. We could sing right with the music, four-part harmony. … Boy, I’ll tell you what, back them days with all those voices—for instance, if you had two or three hundred people in a building and all of them could sing, I mean it was wonderful just to listen to the voices, as people, how they harmonized together.

The singing schools brought a new sound to Southern religious singing, which helped to anchor trends and sounds in what became country music from the beginning. The Carter Family’s experience with shape note singing in southwest Virginia (where A.P. Carter’s uncle was a prominent singing-school teacher in the region), for example, almost certainly had a strong influence on the harmonies that made them a sensation in early country music.8

This background was likely one factor that made the Phipps Family natural and skilled mimics of the Carters. But despite the shape note training, Phipps always viewed his musical sensibility as innate.

“It just came inside of me,” he said. “Nobody said, ‘This is how you pitch it’ at all. … This scale came in my mind.” Likewise with his talent for instruments, which was unusual in his family: “A gift, natural born. I can pick up any instrument. Why I can keep time on a lid.”

It’s interesting that Phipps seems to be so particular about placing an emphasis on unique individual talent given the clear influence of shape note singing and explicit musical training in eastern Kentucky when he was growing up—a factor he also highlights in his recollections. I wonder whether his two impulses on the question of musical ability might reflect broader tensions and themes in rural religious music and its encounter with mass media and the wider world: singing only by the strength of the Spirit and singing with technical skill; music as a pure expression of lived experience in a shared community and music as a product of expertise, training, and individual creative talent; pride in an old-time, downhome identity and pride in virtuosity and technique.

In addition to singing in church, singing was also part of his family’s daily life as Phipps grew up in Barbourville:

It was part of our life at home. We done a lot of singing. We’d gather together around at night, mostly at night. Sometimes of a daytime. We would come in off the farm and we’d have a dinner. They call it lunch now, but called it dinner back them days. We would sit around after a while, after what we called our ‘dinner’ settled, we’d get a songbook and we’d start signing. We might sing for 30 minutes there, enjoy ourselves good, and then we’d go back on the farm and work, hoe our corn or whatever we was doing the rest of the evening. Then we would come in, that evening and we would wash up, have supper, rest a while, and then we’d get our songsbooks and we’d sing maybe for an hour before we went to bed.

They sung four-part harmony without any instrumental accompaniment. But they did have a pump organ in the home, and Phipps recalled neighbors coming over to gather around the organ to play and sing together. “Seems to me like everybody could sing back them days,” he said. “Back them days just about everybody could carry a tune. I mean they knowed music.”

In addition to the home and church, singing was also a major part of social life in the community, including at music parties in the community. These parties, held weekly on Saturday nights on a rotating basis at someone’s home, had been a tradition in Knox County since the first settlements in the area and continued through World War II, after which it died down according to Phipps.

“Musicians would meet together and they’d bring all their instruments together, and they’d play, sometimes all night,” Phipps said. There was no sense of competition or profit motive at these events, he said. Musicians were exposed to variations in tunes from other nearby areas, and people in the community got the chance to catch up, gossip, and hear their favorite songs. There was a religious tenor as well, as many of the singers had made a name for themselves singing in church. Local ministers, including James Phipps, were often influential in spreading the word.

As ever, there was another motive when it came to mingling and music. “Maybe you might be a-looking at one of these girls, too, now and then,” Phipps said.

A.L. met Kathleen Helton at a music party in 1936 at Kathleen’s grandmother’s house a few miles from Barbourville.

“Although we’d lived in the same valley, apparently we were a little distant from one another in the valley,” Phipps said. “But we weren’t distant from one other when we got over to the music parties. We got to be a bit better neighbors.”

“The music was always in our blood”

Kathleen Helton, an only child, was born in 1924 in the Emanuel community, a few miles north of Barbourville. Her family had been in the area nearly as long as the Phippses. Her mother sang and played the organ and was well regarded locally as a musician. Neighbors would call her mother on the telephone when they were feeling lonesome and ask her to play songs for them.9

As a child, Kathleen took an interest in musical instruments, including a ukelele a relative had passed on. “I didn’t know how to chord it, but I’d strum around on that thing,” she said. “Our neighbor would give me a nickel to sing. … Dad said I had a fiddle when I was younger but I tore it up.”

Her father, a coal miner, saved up enough to get her a guitar when she was ten. “Oh, I thought I was rich,” she said. “I couldn’t tune it. I couldn’t do a thing with it, but I’d beat and bang around on it. My cousin would come along and tune it up and I’d keep going to those [music] parties until I learned to play.”

The music parties were a natural forum for Kathleen and A.L. to connect. There was an atmosphere of creative freedom and excitement. People from all over the community got the chance to show off their songs, and no one claimed the floor for too long. You could never quite be sure what might happen or what songs you might hear, and there was room for improvising if not enough musicians showed up. One night, according to Phipps, a banjo player didn’t have anyone to play with and asked for someone “who could do anything.” Phipps started keeping time on a lard bucket lid. “Me and that banjo player really made it,” he said. After that performance, Phipps’ lid-playing became so popular for a time that he wound up with corns on his knuckles.

The area was flush with talent. The year after A.L. was born, the song collectors Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles had showed up in song-rich Knox County for Sharp’s monumental English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. The pioneering musicologist George Pullen Jackson cited the nearby Shenandoah Valley, where Phipps’s ancestors originated from before settling Kentucky, as a hotbed for the tradition of shape-note singing schools in White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands, published a few years before Kathleen and A.L. met.10

The musicians typically had a great variety of songs in their repertoires, and there was seemingly endless variation in how each song was played—so the music was both familiar and new.

“Especially here in the mountains, we had valleys that sometimes you’d never get over in them,” Phipps said. “You might get over there, maybe once in a lifetime, and see who was over there, and listen to somebody sing a song over there. Now they’d come over here, maybe, and listen to us sing a song.” The very same song sounded altogether different depending on the valley.

Kathleen and A.L. kept meeting up at music parties, and their courtship wound up lasting less than a year. They were married in a small ceremony on Labor Day in 1937. He was 21; she was 13.

Marrying A.L. meant that Kathleen soon got shape-note singing instruction from A.L.’s father. “Them being a singing family, if you’d sing at all, you’d get at it,” she said. The connection A.L. and Kathleen had formed at the music party blossomed as they got plenty of time to practice singing together as a couple, and they sang and played music at home, at church, and in the community—just as their families had done for generations. But there were more immediate concerns.

“We wound up in a pretty quick marriage, and then we eased off a little on that music for a while and started raising a family,” Phipps said. “But the music was always in our blood. We’d always come back to it.”

In June of 1939, their first son, Arthur, was born, the first of thirteen children. It was a scary time to start a family, with country still still reeling from the tail end of the Great Depression.

“We found ourselves over here in the deep Depression and the going was rough, no money, no jobs—and no much of anything but get out there and work on that farm and raise your food to survive,” Phipps said. “During the Depression, we had nothing to do. There’s no money in circulation. And them that had the money was holding on to it. … I’ll give Roosevelt one good point and that’s the only I’ll give him. He scared the millionaires into getting out here and investing some money. That helped a terrible lot.”

Phipps briefly worked for the WPA but didn’t like the idea of working for the government and wanted to find better wages to support his family. Eventually, he woke up one morning before daylight and took a passenger train to Pineville, where he changed trains and headed to Middlesboro. That’s where the L&N Railroad Company was headquartered. He decided he would try to talk himself into a job.

“I don’t know why I ever had that dream, but I did,” Phipps said. “I think it maybe cost me fifteen cents to Pineville, maybe ten cents on to Middlesboro. Maybe twenty-five cents was it, and I guess that’s about what I had in my pocket. But I walked into the headquarters of the division engineer. … He was sitting there, and he had one of those green sun visors over him. I asked him for a job and he looked awful surprised that a man would come in there during the Depression and ask for a job on the railroad.”

The engineer told him there were no jobs available, but Phipps wouldn’t leave. “I’ll work anywhere,” he said. “I’ll go anywhere to work. I’ll go in any of these hollers, don’t make any difference to me.”

Eventually, Phipps’ tenacity won over the engineer, who gave him a job doing general labor and maintenance. Phipps worked for the L&N railroad until he retired in 1966.

As A.L. and Kathleen scrapped to bring in enough food and money to support their growing family, they continued to carry on the tradition of their community, singing and playing music together. But now there was a new twist: entrepreneurial dreaming. By the time they were married, talent scouts from the big-city record labels had been roaming rural communities for more than a decade. Suddenly, music might be something more than a tradition. It might even be a career. If people paid money to hear the Carter Family, why not the Phipps Family?

“We had the the desire to get out into the music business, do a lot of shows,” A.L. said. “But we’d say we’d do that next year. So next year didn’t come. We were still right back to the same old thing, farming and working on the railroad.”

To be continued…

Rice conducted interviews with Phipps in Knox County, Kentucky, on May 11 and July 16, 1993. Full recordings and transcripts are available online at the Berea College Sound Archive.

Riddle, a Black musician Carter met on one of his song catching expeditions, helped Carter gain entry to Black communities as well. He also played a vital preservationist role because of his ear, much more refined than Carter’s. Riddle would often memorize the music while Carter wrote down the words, later becoming known as a “human tape recorder.” According to some sources, Riddle also taught Maybelle Carter the blues-inspired guitar style that became famous as the “Carter scratch.”

This would turn out to be a vital—if mostly accidental—act of preservation, but their motivation was financial: Carter would “work up” the songs, allowing him to nab copyrights, even on traditional songs in the public domain.

The provincialism and isolation of the rural South in the pre-radio period can be exaggerated. By the early 1900s, railroads helped connect rural towns to major cities; many Southerners had already begun seeking better jobs in the cities and were moving back and forth, carrying new cultural ideas with them; various types of traveling shows brought music from the North, religious revivals helped spread a variety of musical impulses; and sheet music helped Tin Pan Alley gain footholds far from New York City. Still, in terms of everyday experience, music in rural Southern communities was a genuine folk tradition, typically shared by people who knew each other.

That’s not to say they never played for money. Musicians were hired for square dances, political rallies, and other community events. A few became regional celebrities because of fiddle contests and could command a higher fee. But generally, the first rural folk musicians recorded commercially had full-time working-class or agricultural jobs rather than making a living as musicians.

The story goes that the talented piano player Al Hopkins, whose group recorded six songs for Peer at a 1925 session, told Peer he should come up with a name for the band. “Call the band anything you want,” Hopkins told Peer. “We are nothing but a bunch of hillbillies from North Carolina and Virginia anyway.” Peer dubbed them the Hill Billies; eventually “hillbilly music” became the term for a new genre in commercial recording.

Quoted in David Lewis Taylor’s 1978 masters thesis at Western Kentucky University, They Like to Sing the Old Songs: The A.L. Phipps Family and its Music. Taylor did extensive interviews with members of the Phipps family, and his thesis was an invaluable resource for this project. Unless otherwise noted: all quotations by A.L. Phipps in this piece are from either the Rice interviews or from Taylor’s thesis, and all quotations from Kathleen are from Taylor.

The Old Way of singing had an influence on country music, too, such as the practice of individually “decorating” a note. The Carters and Phippses both grew up in areas where churches still singing lined-out hymnody had a stronghold, and both were likely exposed to this alternate tradition as well. For a discussion on the Old Way’s influence on country music, see Sammie Ann Wicks’s discussion in the journal Popular Music. For more on the Old Regular Baptists and lined-out hymnody, see my 2017 piece in the Oxford American, and a companion podcast episode I hosted and co-produced for the OA in 2023.

This narrative about Kathleen’s early life and her family is based on the account in Taylor’s thesis.

Taylor’s thesis first alerted me to the direct references to Knox County by Sharp and the Shenandoah Valley by Jackson.