Paintings I like

Notes from a dilettante

“Our Hair Has Always Been the Problem,” Arghavan Khosravi (2022)

The best painting we saw at Art Basel last December and one of the most moving single works of contemporary art I’ve seen in years. It’s hard to do this justice with a photograph—it’s a three-dimensional work with a wood panel depicting a guillotine. That string is real and if you look at the image above, you can kind of see the depth of the box frame; there’s basically three panels with different positions—the canvas with the figure’s head and the background, the blade, and then the front with hair coming down.

Arghavan Khosravi was born in Iran shortly after the 1979 Revolution and lived there until about a decade ago. This year, protests broke out throughout the country after the death of Mahsa Amini while in custody of Iranian “morality police,” who had arrested her for allegedly improperly wearing her hijab. Shortly after Amini’s death, Khosravi posted this painting on her Instagram. “Our hair has always been an issue for ‘them,’” she wrote. “F*** them!” Khosravi has posted videos on Instragram of her practice in the craft of painting hair—it’s mesmerizing. “These days when I’m painting hair, I’m filled with anger and hope,” she wrote. “More than ever.”

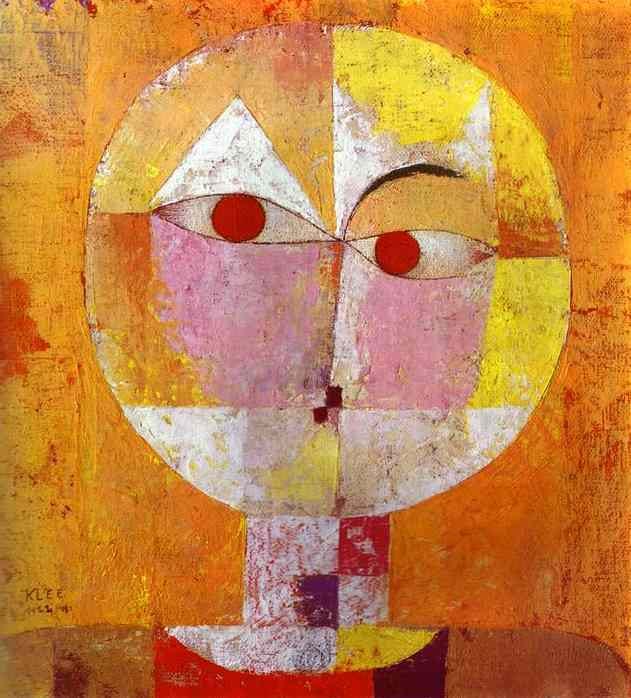

“Senecio,” Paul Klee (1922)

I like how Paul Klee makes color into language.

“Stamford After Brunch,” John Currin (2000)

Across the arts, the story of humans in recent vintage is that people became ever more refined in their craftsmanship until the culture became exhausted. Then photography and motion pictures emerged as a crisis. You never let a crisis go to waste. So we get modernism, broadly speaking, drifting from craft to more abstraction, more subjective vision and voice, more experimentation and surreality. As it happens, quantum physics also comes along to upend classical mechanics. A layman might say that in classical terms, quantum mechanics seems to be metaphysical. The glass we see through is ever darker. Stuff gets weird. But modernity is an arms race, just as refinement was before it. It is not enough to get ever more impressionistic, the inevitable end point is to question the very notion of representation itself. What if we thought as babies do, or our ancestors did 60,000 years ago? Walk around your neighborhood and try to explain to your toddler what the difference is between art and detritus. It’s hard! Place a urinal on a pedestal, and don’t smirk. It’s acculturation all the way down. Free your eyes. But on the other hand, once you’ve put the urinal on the pedestal, there’s a little less oomph when you tape the banana up on the wall decades later. There may be limits to our human range. Even in the arts, we may be computationally bounded observers. So the abstract impressionists were right, in the way that punk rock was right. The point is important, but not inexhaustible. The rebellion against the decadence of refinement becomes its own form of decadence. Modernity was exhausted in decades; post-modernity in years; whatever came next never awoke at all. The reaction to this predicament is nostalgia. If you played the music of today, would it surprise the listeners from twenty or twenty-five years ago? I don’t think so. Nostalgia, like opioids, is addictive and recursive. It is decadence recycled. You might try to get around this by shock, but in the spirit of ’90s nostalgia, I think it’s fair to say that “nothing’s shocking.” There can be no greater disaster for contemporary art than if we enter the galleries and exit unrattled and bored. The anxiety of influence is a low-humming anxiety; it can be paralyzing but also an animating force. Cultural exhaustion is a great depression; it is debilitating in full. In our new century, we find ourselves facing exhaustion piled on exhaustion piled on exhaustion. John Currin began his career making abstract paintings but then sensed the coming exhaustion, understood that he was only doodling in the margins of a chapter that was coming to a close. This was an early and unfashionable realization, around thirty years ago. So he did not try to turn the screw of modernity ever tighter. And though he studied the techniques of the European masters, I don’t think it’s right to say that he looked backwards (his works seem decidedly more modern now—more now—than the work of other major contemporaries of that time). His work was of the moment, yes. But it was inexhaustible. Put aside the titillation factor of his subject matter, that can only explain so much. How did he solve this puzzle? The old tricks of human ingenuity, that’s all: His solution was craft.

“Sari,” Lisa Yuskavage (2015)

Grace pointed out to me that I could write a similar entry as the one above about Lisa Yuskavage.

“Double Self Portrait,” Gary Bolding (2005)

I am biased because he was Grace’s teacher and mentor, but Gary Bolding is my kind of painter. It is not easy to develop a rich narrative in a static form, but Bolding is a natural storyteller and world builder. There’s a kind of implied motion in much of his work, inviting the viewer to imagine what came before and what will happen next. He’s also just very funny. Lots of visual artists have some ironic bite; Bolding manages to deliver discordant tonal notes with visual imagery as uncanny as cinema, to mix my sensory metaphors. I find myself almost woozy with recognition, even as the content veers toward the surreal. “I get a kick out of using fifteenth century technology to tell a somewhat subversive story about life in the twentieth century,” he once said, which sounds about right. This one is a little different but always sticks with me, like an immaculately rendered cosmic joke.

“Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 7, Adulthood,” Hilma af Klint (1907)

Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint’s abstract work, which she began in 1906, was nearly unknown until the mid-1980s. It predates the first abstract paintings of better known pioneers like Kandinsky, Mondrian, and others.

She was deeply devoted throughout her life to spiritualism, a social-religious movement that spread widely in Europe and America around the turn of the century. After death, the spiritualists believed, consciousness persists in the form of spirits. These spirits, who had reached a more advanced state, could be communicated with by the living. During a séance in 1906, af Klint, then forty-three, received a request from a spirit to make paintings on a transcendent plane. They were to be hung in a circular temple. There were yet more instructions, not worth belaboring here. She spent nine years on her “great commission”—The Paintings for the Temple—comprising 193 works.

Among them were a number of smaller series, such as “The Ten Largest.” These ten paintings were to be hung together like a “beautiful wall covering.” They represent the phases of life, from childhood to youth to adulthood to old age.

Regarding the spirit’s instructions for this series, she wrote: “It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the mysteries but that I was to imagine that they were always standing by my side.… Ten paradisiacally beautiful paintings were to be executed; the paintings were to be in colors that would be educational and they would reveal my feelings to me in an economical way…. It was the meaning of the leaders to give the world a glimpse of the system of four parts in the life of man.”

We have a print of another painting from the Temple collection in my daughter’s bedroom. But nothing compares to seeing af Klint’s work in person. We saw a big exhibit a few years back at the Guggenheim in New York and, rare for me, I remember the experience with vivid physicality: I felt overwhelmed by energy and light.

Robin F. Williams, “Swoon at the water pump” (2010)

Williams’s more recent work has taken a very different direction, but this is from my favorite period of hers.

“Fundação de Embu,” Cássio M'Boy (1950s)

Apologies for the photo quality, I took this on my phone at Art Basel. Cássio was a key figure in helping Embu, a small city in the Brazilian state of São Paulo, become a major center for the arts. “Fundação de Embu” (Embu’s Foundation), as best as I can tell from the wall placard, represents a mythic origin story of the city of Embu. Cássio da Rocha Matos himself took the name “M’Boy” in honor of the city; from the placard:

“Embu” derives from the name of the Jesuit village which originated the city, “Mboy,” a term derived from the ancient Tupi “mbol’y”—River of the Snakes—or simply “mbola”—snakes.

Well before I read the placard, this one got me from twenty meters away. My eyes just stuck to it as I got closer and closer. Color and space. It’s quiet and perfect.

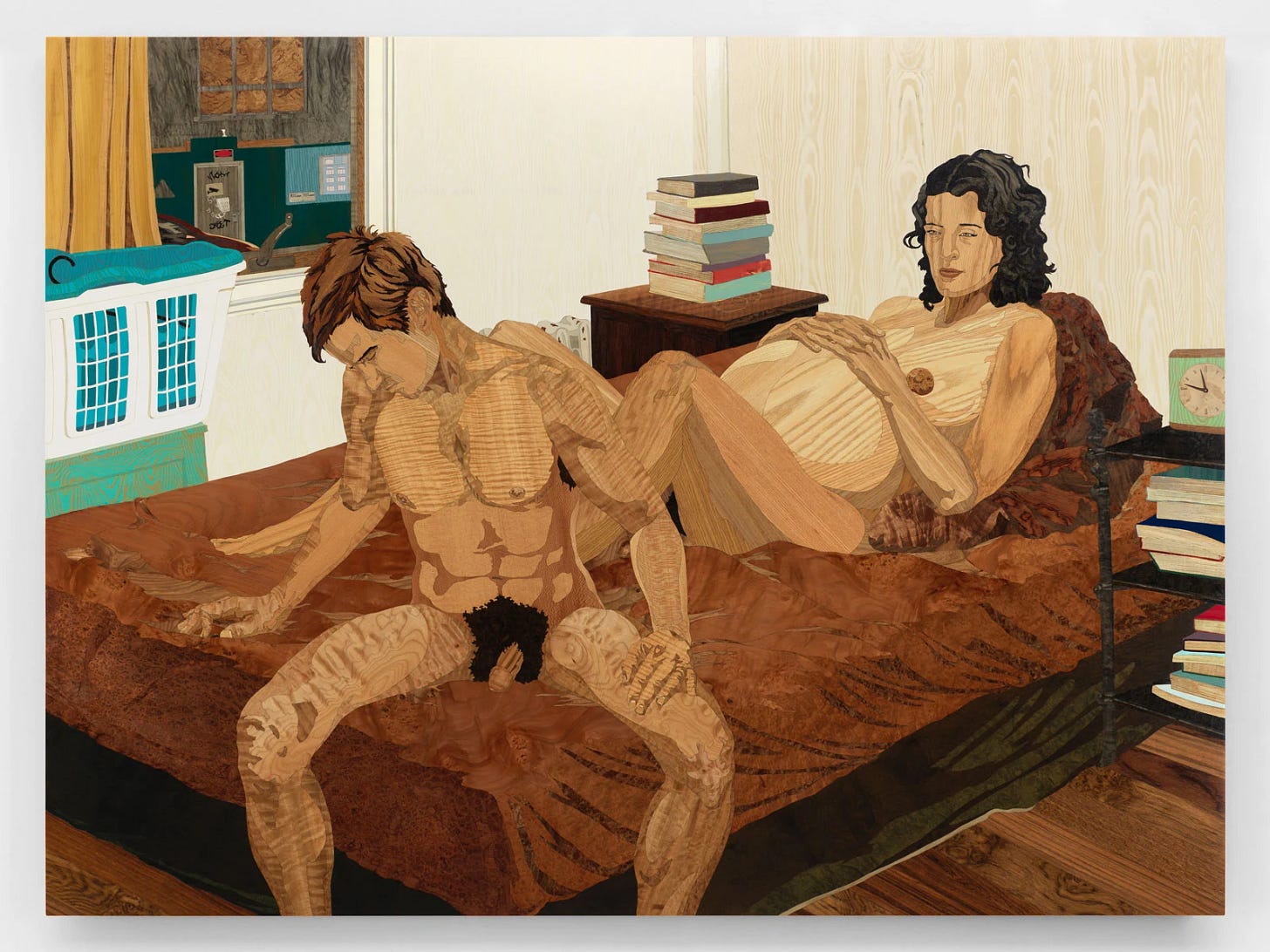

“On Thinking Thoughts are Feelings,” Alison Elizabeth Taylor (2020)

Taylor employs Renaissance-style marquetry, which she typically combines with painting or sometimes photography, in a remarkable hybrid. The only reason I know what the word “marquetry” means is that it once came up when I was fact checking a magazine article about incredibly expensive board games. Marquetry is the craft of applying veneers to a surface such as wood to create decorative patterns (as opposed to the older practice of inlay, which involves cutting out spaces to insert small pieces of another material). Think lavish furniture at Versailles—Louis XIV is said to be the one who popularized marquetry.

The decorative mode insists on beauty, let’s say. It insists on the romantic notion that an object can be imbued with meaning, can outlast its transitory circumstance. Taylor uses this elaborate old technique to depict modern, quotidian scenes. There is something incredibly moving and intimate about the care and intricacy given to these images—as if these otherwise forgotten moments are given permanence by Taylor’s attention.

postscript:

“When I had a loft with Sean and Kevin Landers, we’d always take a break in the afternoon and watch The Golden Girls,” John Currin explained. “When I made the painting, I was living in Hoboken and still making abstract paintings, and I was very frustrated. I was walking back from the PATH train and this vision of Bea Arthur just came to me.”

p.p.s.

This helps give some idea of the scale and grandeur of af Klint’s work, from the Guggenheim exhibition: