On the transmigration of souls

Leaving Las Vegas

I’ve only been to Las Vegas once, the first stop on a cross-country roadtrip with my friend Thanner. I think if you’re not a gambling addict, it’s kind of a boring place? I don’t know. We were twenty-two years old and we wanted to get drunk and have a good time. But everywhere we went there were bright lights and sad seniors. We lingered in places that would give us free drinks, until they stopped giving us free drinks, and then we’d find another spot. The air smelled dirty and clean at the same time.

We were traveling with a dog named Riot who belonged to Thanner’s girlfriend. We could find only one cheap motel that would take a dog, and it was maybe five miles from the Strip, so we took a bus there on the night we went out on the town. My memory, actually, is that it was ten miles away, but that can’t be true.

“I thought people had fun here,” I said.

“They are having something,” Thanner said. “Something other than fun, but something.”

Luckily, I had recently graduated from college and so I had those little blue amphetamine pills in my pocket. We had one or two of those and then we started having a good time after all. We became chatty and we chatted. We gambled a little and drank a lot. Bad gin and tonics. We kept riding the escalator up and down and talking about the events of the last six months and imagining the events of the next six months. I told him how the main thing I wanted was to not write anything down. He told me he missed his girlfriend. And he kind of missed her dog. In that moment, he wished we were riding the escalator with Riot. He might not have used the word “girlfriend.” We might have discussed the terms of their relationship, or we might have discussed how the terms of their relationship did not matter. He worried that my shoelaces, untied, would get caught in the escalator. They won’t get caught, I promised him. We said many other things, but of course I can’t remember them now. At the time, I was not writing anything down.

I could have said, but did not say, that according to Phillipe Petit, the man who walked the high wire between the tops of the Twin Towers in 1974, vertigo is not the fear of falling, it’s the fear that you will jump. And Thanner might have informed me, but did not, that according to the ancient Chinese Zhuangzi, Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. There is existence without limitation; there is continuity without a starting point.

But we actually did say other stuff, probably stuff like that. The American roadtrip gets you in a certain mood. We were drooling with possibility. That’s the wrong metaphor—our mouths were dry on account of the drugs. The phrase “foreseeable future” is funny when you think about it. The future is not foreseeable.

We kept talking and talking and we did not say, though we might have thought it, that every trivial trip and skip in our conversation was precious. We had originally met at a kind of hippie church camp, where they liked to talk about the inherent worth and dignity of every human being. We didn’t believe in church things at the time, but we believed in that. Our lives and the life of every sad senior at the slots—they were sacred. They were immeasurably beautiful. And what were they made of, really? Stuff like this. Talking on the escalator, up and down. The astonishing present tense. Over and over, that’s a life. It is impossible to hold that, to know it. But with gin and speed as our witness, we would have known it then, I think.

And up and down we went until we tired of that and wandered through the casinos once more. Until we tired of that and looked for food but then lost our appetite. At a certain point, we were tired of being so undeniably and irrecoverably in Las Vegas. We decided to go back to our hotel. We were out of place. It seemed that we had the wrong clothing, or were speaking with the wrong voices. This was something that kept happening to us, because we were young, and noticing ourselves, and not realizing that probably no one was noticing us. Their attention was on the slots.

We started to walk away from the bright lights to flag a cab. We were still feeling good. I can’t remember if it seemed like it was going to be hard to find a cab or if we wanted to save money or what. But I remember that Thanner said, “let’s just walk there,” with a forceful resolve that was a bit out of character, and I was immediately convinced. This was an outrageous decision. We had to walk ten miles to get back. I know I hedged with five earlier, but I really do think it was ten miles. I texted Thanner just now and asked what he remembered, and he immediately said ten. Anyway, it was a long way home.

We were really talking now, and walking extremely fast. At some point, Thanner began limping.

“Are you hurt?” I asked.

“Let’s keep moving,” he said. He was getting a little worried about Riot the dog. Riot had issues with separation anxiety.

We kept walking fast. We talked more, then a bit less. Thanner’s limp got worse. “You sprained your ankle,” I told him. We kept walking.

We were maybe a mile away when we encountered a man on the otherwise empty street. It was now well into the wee hours of the morning. I have a visual memory that we met him right as he got dropped off by a bus but I think that’s wrong. In any event, he was excited to see us. He looked rough. But really, he probably didn’t look much different than us. He came up to speak with us with some urgency. That was all right by us. We were feeling pretty urgent ourselves.

He was talking wild and fast, very much in the manner that we had been doing a bit earlier. He asked us if we wanted drugs. We said we were all right. Then almost as an afterthought, he went into a manic monologue. He had just gotten into town from California. He had been working construction. (I don’t remember this part but Thanner remembers that he was working on some kind of fancy house, maybe building a pool.) He was dissatisfied with the work. His boss was an asshole. So he picked up a hammer and hit his boss in the face with it and then walked off the work site and caught a Greyhound to Vegas.

Or something like that. It was hard to follow what he was saying. Then he was asking us what to do. So what do I do, guys, what do I do? He asked us again if we wanted drugs. Never mind about that, we said. I told him the situation was bad. It was serious. This was the only real help I was able to offer. I don’t think it had occurred to him before, that it was serious, but it occurred to him now. He took off down the street. I worried for him, and I worried for his poor asshole boss. But we had to get back to the hotel. We had to go check on Riot.

By the time we got there, it was maybe 5:00 in the morning. We were no longer speedy. We were utterly exhausted. Thanner’s ankle was cartoonishly swollen.

“Rice,” I told him.

“What?”

“Rest, ice, compression, elevation.”

Riot was very happy to see us and curled up with Thanner on one bed while I plopped down on the other one and we immediately fell sound asleep.

We had been asleep for not much more than an hour when Thanner’s phone started vibrating. It kept vibrating. I guess it must have been across the room. I didn’t have a cell phone back then. It was confusing—it couldn’t have been too much past 6:00 in the morning! Who would be calling us? But it just kept buzzing. We were already hung over and had barely gone to sleep.

“No,” Thanner groaned. “No.”

The calls continued for maybe half an hour. Eventually he groaned again and rolled out of bed. He shouted in pain as he tested his ankle and then limped over to the phone and saw that his girlfriend had been calling him over and over and over. The phone buzzed once again and he answered.

This was in the fall, almost twenty-two years ago. Come this September, I will have lived more since then than I had prior to that moment in the hotel room. And so the first-person character in this story is something like a stranger to me now.

I rolled over and opened one eye. I was confused. Thanner answered the phone. His girlfriend was frantic. She told us we had to get in the car and go, immediately. The sun had come up in Vegas. It was September 11, 2001.

I think by the time we finally picked up the phone, the first tower had just fallen. “You mean it’s not there?” I asked. I don’t remember who this question was directed to.

It seemed at that moment like more planes would crash into more buildings. We’re going to sound like buffoons here, but at the time we were worried that Vegas would be an obvious target. A grotesque symbol of America. Plus they literally had miniature versions of famous world landmarks and a miniature Manhattan skyline! I don’t know. It just seemed very clear to us that we needed to get out of there right away and go to Utah or something.

And so we did. It suddenly seemed dicey to call out the dog’s name. “Riot! Riot!”

We were cracked out and beat as we drove northeast on Interstate 15 in my ’91 Honda Accord. We were in disbelief. I want to try to be true to how I was feeling at the time, which is hard to do now, reflecting back on a Moment in History. But at that point, we were so disassociated from the American communal experience. We were eating road snacks and using paper maps to navigate to southwest Utah. We were very tired.

Back in Vegas, strangers were having conversations. Bellhops and dealers and gamblers and strippers and backing bands and lighting techs and hookers and johns and chefs and waitresses and dishwashers and bachelor partiers and DJs and janitors and bartenders and drunks. Everyone stopped what they were doing; everyone kept doing what they were doing. Some of them were talking about what it might all mean, which made the meaning then and there: a collective act of creation. The story this chatter created would linger as background for years to the hum and hue of our lives. People kept playing the slots. When it happened, in the aftermath, as the news spread—some people did not draw their eyes away from the slot machines even for a moment. As the reports came in, they were watching the lights spin with possibility.

But I am only speculating—we were not there, we had left Las Vegas, we had left the crowd, left the casino, left the lights. We were worried and discombobulated. But we were also fizzy with adrenaline, and our spirits were good. Our situation was untroubled but it had the feel of a predicament. This is the particular disassociation of the twenty-two year old: Sometimes you are not so much experiencing something as laughing at your own predicament. Like everyone, we had watched too many movies. The movie we were watching now was about two doofuses on the American road while the towers fell. It would be a day later that we tried and failed to reach friends and family in New York to make sure they were okay (they all were okay, as it turned out, or as okay as they could be). We were driving through the desert with the windows cracked. Sometimes the air conditioning worked, sometimes it didn’t. Riot was happy. He liked to be with us and he liked to ride in the car.

I remember two things from that day’s drive. Maybe you will think I am making them up because they are so overwrought and surreal, but I promise you, this is what happened.

Pretty much everything was normal as we drove along. But then we passed a gas station that was charging some outrageous amount, like $10 a gallon or something. This freaked us out. It’s a dumb caricature of the American experience that high gas prices are the universal symbol of the apocalypse but this was the moment when we really got nervous. And we were on a stretch where gas stations were few and far between, so it took us quite a while before we passed another station, and then another, with totally normal prices. It was just one wild gouger in the desert. Maybe he was just scared.

Then the second thing I remember is that we were listening to the radio and a weather report came on. And the forecaster said something like, “We’re looking at partly cloudy skies this afternoon.” Then paused. “Not that that matters. Anymore.”

This really tickled us and I am sorry to say that in this moment of collective American grief we were laughing hysterically. An existential weather report! We concluded that the weather matters exactly as much as it matters, yesterday and today and tomorrow.

Eventually we got to Utah and went camping and hiking in Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Arches. We talked to strangers here and there, but we did not talk about the news. The terrain looked like we were on Mars. It was beautiful. We simply didn’t hear anything at all about September 11 for that entire week.

Then we went to Denver and visited a friend whose social circle centered on a punk-rock anarchist collective house. And we got there and realized that across the country, this had been all anyone was talking about while we were camping. Our punk-rock hosts were extremely generous but perhaps having slightly atypical conversations. The first night we were hanging out, I was trying to talk my way through the gravity of what had occurred and someone said, “right, you’re asking the question we’re all asking.” I didn’t know what the question was and asked for a hint. He said: “The question is, was this an effective attack on American capitalism?” Not for the first time, I found myself a sweater at a sweatshirt party, and looked down sheepishly into my beer.

About a year later, John Adams premiered his piece “On the Transmigration of Souls” at the New York Philharmonic. I’m not sure if this is what Adams had in mind, but in the ancient Indian concept of Saṃsāra, the transmigration of souls is cyclical. The Greeks called it metempsychosis. You are born and you die and you are born again, die again, and so on.

Adams’ piece is a triumph of emotive sound, but it’s almost too good. I have trouble listening to it. I recently heard an interview with Adams describing the genesis of the piece:

I came up with the idea of what I called a memory space, where the various texts and words and phrases could float, so to speak, in musical space. The listener would enter into that space the way you might enter into, let’s say, a big cathedral in Europe and just be alone and experience your emotions and your thoughts as they unite with these musical objects.

The musical objects came from all different things. The texts that I put together came from little handmade signs that family members left around Ground Zero, hoping that they would find their loved ones.

In an interview at the time of the premiere, Adams said that one inspiration for his piece was amateur video footage he had seen, taken minutes after the first plane hit: “millions and millions and millions of pieces of paper floating out of the windows of the burning skyscraper and creating a virtual blizzard of white paper slowly drifting down to earth.”

In 2019, my family moved to Jersey City, where we lived for two years. We could walk to Liberty State Park—or take a longer walk to the waterfront by Exchange Place—and see stunning views of lower Manhattan just across the Hudson. We lived about a mile and a half from the apartment at 251 Virginia Avenue in Jersey City where Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, lived with co-conspirators. I don’t know the precise spot, but I strolled along the waterfront so many times that I must have stopped to look at the skyline a time or two in the same place where Yousef stood and watched the 1993 explosion happen across the water—disappointed that it didn’t topple both towers.

To my daughter, the skyline looked exactly as it was supposed to look, exactly as it always was. I would point and tell her the names of the skyscrapers. She had an uncanny memory for them, and enjoyed identifying them herself. One World Trade, the Trump building; further uptown, the Empire State Building and the Woolworth Building; the Goldman Sachs building on our side of the river, and so on. This didn’t even seem odd at the time, but she would have us pretend to be skyscrapers. “Pretend that you’re the Chrysler Building and I’m One World Trade,” she would say. And that was it, that was the whole of the game, you were just supposed to stand there with that knowledge internalized: I am the Chrysler Building.

We had a nice view of the Statue of Liberty from Liberty State Park, but even walking up all the way to the bridge leading to Ellis Island, it’s far enough away to look small. In Las Vegas, the replica statue is two fifths the size, but you can walk right up to it at the New York-New York Hotel and Casino downtown, on the corner of Tropicana Avenue and Las Vegas Boulevard. There’s also a miniature replica of major sites from the NYC skyline there, including the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Grand Central Terminal, the New Yorker Hotel, and so on. My daughter would love it.

The Vegas Statue of Liberty is not as sturdy as the real thing. It’s made of styrofoam with reinforced fiberglass and drywall.

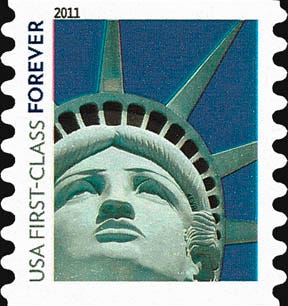

In December 2010, the U.S. Post Office mistakenly used an image of the Vegas replica for its Statue of Liberty forever stamp rather than the real thing. Officials had found the image on Getty Images.

Even after they realized the mixup, the post office kept issuing the stamp. People liked it. The fake looked nice on the stamp. But America the beautiful is a litigious land. Artist Robert Davidson, who designed the Vegas statue, filed a copyright lawsuit against the post office in 2013. Davidson argued that his version was not just a copy of the original; it was “more ‘fresh-faced,’ ‘sultry’ and even ‘sexier’ than the original located in New York,” according to his lawsuit—with notable differences in the chin, the lips, the eyelids, the ear lobes, the patterns of the robe folds, and other features. He drew inspiration for the visage from his mother-in-law’s face, he said. In 2018, a federal court ordered the post office to pay Davidson $3.5 million in damages.

When Thanner and I drove away more than two decades ago, I figured I’d be back to Las Vegas some day, but I’ve never returned. In 1987, covering the Mike Tyson-James “Bonecrusher” Smith fight for the Village Voice, Joyce Carol Oates wrote that Vegas is “our exemplary American city”:

Incongruity, like vulgarity, is not a concept in Las Vegas. This fantasyland for adults, with its winking neon skyline, its twenty-four-hour clockless casinos, its slots, craps, Keno, roulette, baccarat, blackjack et al., created by fiat when the Nevada legislature passed a law legalizing gambling in 1931, exists as a counterworld to our own. There is no day here—the enormous casinos are pure interiority, like the inside of a skull. Gambling, as Francois Mauriac once said, is continuous suicide: if suicide, yet continuous. There is no past, no significant future, only an eternal and always optimistic present tense. Vegas is our exemplary American city, a congeries of hotels in the desert, shrines of chance in which, presumably, we are all equal as we are not equal before the law, or God, or one another. One sees in the casinos, especially at the slot machines, those acres and acres of slot machines, men and women of all ages, races, types, degrees of probable or improbable intelligence, as hopefully attentive to their machines as writers and academicians are to their word processors. If one keeps on, faithfully, obsessively, one will surely hit The Jackpot. (You know it’s The Jackpot when your machine lights up, a goofy melody ensues, and a flood of coins like a lascivious Greek god comes tumbling into your lap.)

Oates concludes, “The reedy dialects of irony—the habitual tone of the cultural critic in twentieth-century America—are as foreign here as snow, or naturally green grass.”

The Las Vegas roadtrip was just one leg in a longer journey: After I graduated from college, I drove around the country for fifteen months, sometimes stopping somewhere for a few weeks. I started out with a little money saved up and periodically worked odd jobs—helping out at a farm, construction work I was hopelessly unqualified for, serving smoothies at a Smoothie King, working the register at an art supply store in the Bay Area where James Hetfield shopped, knocking door to door for Ralph Nader’s public interest research group, teaching gifted kids at a summer program, various office and temp jobs, etc. Most of my money went to gas. Lots of friends fed me and lent a couch to sleep on.

I saw Niagra Falls and the Grand Canyon and the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota. I visited the Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo. I had a late night drinking with a future cable news host by Lake Michigan. I walked through the badlands with an old friend, though I suppose she wasn’t an old friend quite yet. I went to juke joints outside of Indianola, Mississippi. I got some stares so I bought some drinks, and it was all right. I went to a strip club in Sante Fe, New Mexico, because it was the only thing open at night. That was dreary. I ran around the streets in New York City with one of my oldest friends and we caused more trouble than we deserved to get away with. The next morning, hungover, we hung out with a couple of his buddies and one of them told the story of oversleeping and missing a job interview he had at the World Trade Center the morning of September 11. They all laughed so hard they held their guts in pain.

I visited my grandparents in Yorktown and my grandmother, by habit, told me that I had grown. She wondered about my beard. “People are going to think you are an A-rab,” she said—“as they say.” I went to visit Ike Turner’s childhood home in Clarksdale, Mississippi. I don’t know why. It’s not a landmark or anything. I drove there and parked my car across the street and got out and looked. It was just a house. Someone was sitting on the porch and waved happily. I swam in the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf. I had a really nice time in Minneapolis and we went swimming in three or four different lakes. I missed North Dakota, and regret it. I saw an alt-country singer in Nashville at the Slow Bar, a great bar that no longer exists. He was drunk and kept yelling, “Fuck Nashville!” When I was still with Thanner, we stood vigil overnight at a 24-hour memorial in Washington, D.C. for political prisoners in a country I am ashamed to admit I can no longer recall. There was a recreation of the cramped prison cell. We were there mostly because we had nowhere else to go that night. We stayed up all night, as agreed.

I ate psychedelic mushrooms and stared up at the redwoods and was wowed. I went to Mardi Gras for the first time and gave away my cowboy hat to a woman I walked around with for a bit and kissed and then never saw again. I don’t remember why I even had a cowboy hat. I stopped at that confusing Wall Drug place in South Dakota with all the roadside signs on Interstate 90. I had questions about the signs that were not answered by stopping there. I ate green chiles in New Mexico and had the fanciest coffee I’d ever had in Portland. Around Christmas, I thought of stopping, but a friend told me I needed to see it through the year.

One friend I was driving with opened the sunroof as we drove through Montana and tried to take a picture of the sky because it seemed so big. In Yellowstone, I thought I heard a bear just outside my tent, but it turned out to just be someone snoring in another tent. In Idaho, the telephone wires cut through the terrain like giant veins pumping through the land. I went up to Montreal and I didn’t remember much French. I saw buffalo wandering on the side of the road in a state out west that I now can’t recall. I walked down the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and ran into a friend of a friend, and she became my friend, too.

I drove across the tiered-arch I-40 bridge between Tennessee and Arkansas half a dozen times. I just called it the I-40 bridge. I had no idea it was named for Hernando de Soto, a Spanish conquistador who helped slaughter various groups of indigenous peoples in what is now Nicaragua and Peru, and later led the first European expedition to cross the Mississippi River.

On the Memphis side of I-40, there was this pyramid stadium where the University of Memphis then played basketball, and it was weirdly beautiful. Originally, it was called the Great American Pyramid. It was sided with stainless steel, which looked like glass when you drove by. I remember thinking it was garish but somehow perfect—though critics in the city complained it didn’t get much use.

Later, the pyramid became a Bass Pro Shop megastore. Later still, road traffic on the I-40 bridge had to be shut down for nearly three months due to a major crack in a hollow steel girder. It would have seemed unthinkable back then, as I drove the familiar 3.3 miles, that in twenty years time the bridge would be in imminent danger of collapse. I loved that bridge, driving into wide open Memphis, or heading into Arkansas where the interstate roads suddenly got worse. Watching the boats go by. Some people call it the “M bridge” because of the two arches. I am not ashamed to tell you that every single time I crossed, I put on the Paul Simon album Graceland. And it felt so good to cross that bridge listening to Graceland, every time, it was like a libido of bald eagles were diving in unison into the mighty Mississippi River.

In February, if I’m remembering the dates right, I was in Oakland, staying with the woman I had dated my senior year of college. We were having a good time hanging out and a difficult time hashing out the past and the future.

On February 12, at a press briefing, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said, “Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know.”

Rumsfeld continued: “But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

Twenty years later, I would hear scientists suggest that at the level of fundamental physics, there was nothing special about the present—that the past and the future were just as real, whatever that might mean. We perceive the past to no longer be real and the future to not yet be real. But perhaps time’s arrow only appears to have a linear direction because we are wired to observe it that way. I don’t know. I do know that in February 2002, I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

That fall I took a job at a magazine and my grownup life began. I had other jobs and spent more carnival seasons in New Orleans and got married and had kids and bought a house.

At a townhall meeting in 2004, Rumsfeld said, “You go to war with the army you have.” Two years later, he resigned.

I am in the minority here, but Jersey City is one of my favorite cities in the United States of America. I don’t know why, it just is.

A lot of people there commute to New York for work across the river. In Liberty State Park, there’s a monument honoring all of the New Jersey residents who died on September 11. I had no idea it was there until my daughter and I wandered up to it one day on a walk in the park. It’s a beautiful piece. There are two parallel stainless steel walls, 210 feet long and 30 feet tall, with a 12-foot paved bluestone path between them. The names of 749 people with ties to New Jersey who died at the World Trade Center are engraved on the walls. The 210-foot length of each wall is the same as the width of each side of the towers; I believe the silhouette of the memorial falls roughly in the same place that the towers used to loom on the other side of the Hudson. It’s called Empty Sky.

My daughter called it “the tunnel” and loved it. We walked between the great big walls and out the other side and she asked to do it again. I might have thought, but did not think, that my daughter’s future was a known unknown. Or perhaps her future is happening, so to speak, at another point in time that only seems like an unrealized linear point in the future from the perspective of this observer.

Who can say. But there, in what was then the present tense, she realized there was a nice acoustic effect if you shout-sang at a high octave and high volume, like a human trumpet. I wasn’t sure this was a good idea and told her so, but she respectfully disagreed. Then she began to run, trumpeting at the top of her lungs, and letting her fingers run along the walls with all those names. She did not know that they were names, that these names belonged to people, that these people had lives, that these lives were sacred. She just liked the way the indentations felt against her fingers.

I ran to catch up with her because there were other people there, and I worried that she was ruining the experience, that she was goofing on hallowed ground. But I was wrong. Everyone was delighted and laughing, all these strangers. My daughter was delighted, too. She was at just that age when no stranger is a stranger.

“Yes!” said an older gentleman, clapping, as she ran by him. He was giggling and clapping as he watched her run toward the light. “That’s it!” he said. “Yes!”

Didn't get around to reading this one until just now. I love it!

One interesting thing about the crack in the Memphis bridge that I bet would pique your interest, if you don't know this already: It may have been there from the time the M bridge was first assembled, back in the 70s. Not that it would have been visible at the time, but the metallurgical postmortem of the damaged girder indicated it was likely the product of outdated welding techniques that can lead to what's called "hydrogen cracking." All those decades, there was a subsurface fissure lurking in the steel, just waiting for the right combination of forces to trigger its growth.

Well, also: I assume it wasn't visible back when you were road tripping, but actually we don't know how long it was big enough to see. Since 2016 at least, probably 2014, very possibly longer! And we only know it was around during those earlier years because of random people kayaking or taking riverboat cruises on the Mississippi who, after the news of the bridge closure in 2021, dug through their old photographs and noticed a tiny, thin line on that member of the bridge, at that exact point.

Wait, or, did I make you edit these stories and this is all extremely old news to you? If so, I'm sorry.