We’ll go on vacation, but we don’t really care to go see Rome or anything. We just want to play dominoes. We like the fact that we can say, ‘Oh, we went to Rome.’ ‘Well, what’d you do in Rome?’ ‘Played dominoes.’

—Jimmy Butler

On Saturday night, I was in South Beach, and watched Game 6 of the NBA Eastern Conference finals at a dive bar with a friend. The Miami Heat were up three games to two over the Boston Celtics—a win would send them to the Finals. I picked a bar close to the hotel where my wife and kids were sleeping.

We were not far from the party boys in white suit jackets, shirtless underneath—who do not particularly care about basketball, but care deeply about partying, about victory, about the double victory of 1) your team is winning and 2) you are winning in another way, you are on South Beach, you have a white jacket, you are shirtless underneath, life is incandescent.

I love these bandwagon boys and their untroubled joy and would have been happy to have a cocktail-in-a-box with them. But I am a dad who had to hurry back to the hotel room in case the kids woke up. I was pacing myself like a dad and dressed like a dad. I am a dad who has has given up most hobbies and obsessions except for this one: The NBA playoffs consume my attention in late spring and early summer, still—just as they did when I was a boy.

And I still find myself caring too much about what happens, about how ten men on the court navigate space, recognize their teammates and opponents in motion, use unimaginable speed and power to gain these tiny advantages—these little enclaves of real estate on the floor or in the air—and when their speed and power is not enough, they use their guile and timing and tricks; they are operating as individuals with their own slate of skills to survive these countless little battles at the same time as they are operating as a team, a small community that has been practicing endlessly to accentuate their strengths and hide their weaknesses. They’re trying to get the ball into the basket. Then they try to stop the other side from getting the ball in the basket. It dazzles me.

I am a New Orleans Pelicans fan, but otherwise, most of the time I don’t have a very strong rooting interest in a given matchup. When I say I care too much, I mean that I am overly invested in seeing just how the contingent possibilities of the players on the court sort themselves out over forty-eight minutes of playing time.

But there in South Beach, I also found that I cared too much about who won. Because over the course of these playoffs, I have enjoyed watching Jimmy Butler lead the way for the Miami Heat so much that…I just want more of it. More Jimmy. And I want to see him hoist the trophy at the end. Basketball is like this: A certain player can get on a certain kind of roll with a certain kind of style and you just find yourself smitten. This year, this playoffs, Jimmy is my guy.

He played a bad Game 6, but willed himself into points the Heat desperately needed down the stretch, and hit three free throws to go up by one with three seconds remaining. South Beach, even our dive bar, was ready to party. But then Derrick White snagged a miracle tip for the Celtics at the buzzer, sending the series to a Game 7. I have been in cities when the hometown team lost in heartbreaking fashion, when the noises and rhythms of urban life seem to hang heavy with gloom. But I have to say Miami is a little different. People were very amped to win, but not particularly bummed to lose. They were still in South Beach. They were still winning. They would find another reason to celebrate.

In any event, things worked out for the Heat in the end. Monday night, in Game 7, they blew out the Celtics in Boston. They began the playoffs seeded at the bottom of the tournament as the #8 seed, and now they are going to the Finals. On Monday, Jimmy looked gassed. I hope he has something left. The tournament is not over.

To become a professional athlete requires supreme confidence and surely some level of rosy optimism in the story you tell about yourself, the challenges you face, the long arc of your victories and defeats. But I think at the highest levels, it requires a brand of anxiety, too. You always have to keep up with the Joneses, even if the Joneses is mostly just yourself.

Jimmy Butler will make the Hall of Fame, but he has not won a championship. For better or worse, the very best players are judged on championships, an outcome even the very best players can’t fully control. Wins depend on teammates, and opponents, and the way those countless contingent possibilities break across forty-eight minutes; to win a championship, a team must win sixteen playoff games, each win subject to its own contingencies. “Everything can turn on a trifle,” longtime NBA assistant Tex Winter liked to say. A player like Jimmy Butler knows that things can turn against him in ways that he cannot control, which only makes every moment of every possession that he can control that much more precious.

Earlier in the playoffs, Jimmy declared himself the best player in the world. That is not true, and on some level he probably knows that. But sometimes, some nights, it can be true—and he knows that, too.

Butler has become renowned for outperforming his regular season stats during the playoffs. “This is the time to really hoop, when I play at my best,” he explained in an interview a few years ago. “I’m willing to do whatever it takes to win. I would like to think that I’m a winning player. I haven’t won what I want to win yet, but I’m not a loser.”

When we’re not competing at a high level, I’m singing all the time.

—Jimmy Butler

When Jimmy Butler was at Marquette, he sometimes slept at the practice facility with a sleeping bag so he could get every possible minute on the court. As a young NBA player, he rented out a place for the summer with no internet or cable so the only thing to do was train, work out, and sleep. Relatable.

He is a maniac. But he is our maniac.

Shortly after a legendary practice when he was with the Timberwolves, he said to a reporter, “Who’s the most talented player on our team? KAT. Who’s the most God-gifted player on our team? Wigs. Wigs got the longest arms, the biggest hands, can jump the highest, can run the fastest. But, like, who plays the hardest? Me. I play hard. I play really hard. I put my body on the line every damn practice. Every day in the games. That's my passion. That’s how I give to the game.”

And then another time, he told a reporter, “It’s not all fine and dandy, but a smile can go a long way.”

Who is Jimmy Butler in The Breakfast Club? He is everyone. He is the brain, he is the athlete, he is the basket case, he is the princess, he is the criminal.

He could only be named Jimmy, the only name that encompasses the full range of cartoonish archetypes that inhabit Jimmy Butler. He is a Jimmy in every sense of the name: He is the jovial fishmonger from Staten Island; he is the bouncer at a club in East St. Louis; he is the beloved first son lost at war; he is the happy-go-lucky kid who scored free tickets to the circus. He is slapping your back at the biggest auto dealership in Texas and there is a giant billboard with his face and he smiling at you from above the highway and the billboard says: JIMMY! He is the fixer. He is the quarterback. He is the rebel. He is the mayor and he has been the mayor as long as anyone can remember. Everyone knows Jimmy. He is Chicago—that’s not where Jimmy Butler is actually from but there is something true about it, Jimmy from Chicago, a truth squandered by your Chicago Bulls. He is the uncle at the wedding that no one forgets. You know the one: at the end of the night he is still up, still talking, still holding court with a cigar in his mouth, you have had too much to drink and you can’t help yourself, you are shouting out as he approaches, not just you but everyone still awake in the wee hours after the wedding is shouting it out, too: Jimmy! Jimmy! Jimmy!

This is part of what makes him so endearing. He is clearly one of the fiercest, toughest, most maniacal players in the NBA, and a sneering, menacing trash talker on the floor. But he doesn’t register as mean in the way that Bruce Brown Jr. or Draymond Green do, or Kevin Garnett once did. Jimmy is charming, huggable, and sweet. He has a great smile. He loves coffee. He thinks high-quality latte art should be considered a Wonder of the World. He tried to learn himself but his images kept turning out looking like a butt. He loves to have a good time with his friends. He quotes DJ Khaled when talking about prepping for a game. Lately he’s getting into country music. He seems like one of the most likely players in the NBA to strangle someone on the floor; he also seems like he would be one of the most absolutely delightful to hang out with on a Friday night.

He is a good dog; he is a bad dog; he is a dog.

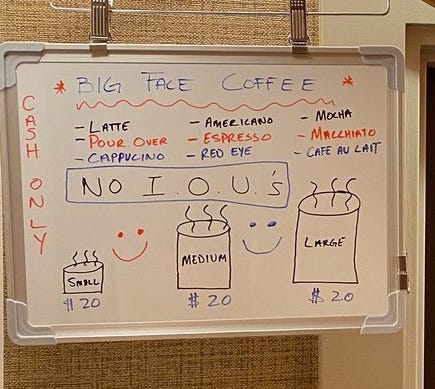

Jimmy is genuinely funny, committed to his gags with a sly ease, surprising and human in his interviews. He has good vibes. The best vibes. During the NBA bubble, when the players were sequestered in Walt Disney World during the pandemic for the playoffs, Jimmy shipped in high-end espresso machines and started selling $20 cups of coffee. People bought them. That’s just Jimmy.

He is a sort of a polar opposite to Michael Jordan: MJ had an effortless style as a player and was tediously effortful as a pitchman; Jimmy has an extremely labored style as a player but is effortless as a salesman, a comedian, a charmer.

On the court, Jimmy doesn’t typically blow by defenders, and while he is clearly one of the strongest perimeter players in the league, he doesn’t overpower defenders all the way to the cup very often. Instead he nudges, probes, dribbles, spins, pivots, shoulders—a kind of rough-and-tumble dance to find a little bit of space where he is comfortable shooting. He finds that little bit of real estate and then he’s in motion getting his shot up while the defender is still trying to jockey with all of Jimmy’s shimmies, and there it is, another two points. It doesn’t immediately blow you away, but it is such a reliable way to get a pretty good shot against even elite defense that it all adds up.

Or: he doesn’t need to make the basket, because he has tricked his defender, lured him to the wrong place at the wrong time—and if his defender is out of legal guarding position for even a half a second, Jimmy will process it and immediately find his way to contact, find a way to conjure a collision with even the most disciplined foe. It is just so to say that he “draws” a foul; the defender pleads with the ref but the rules are the rules and Jimmy has pulled the defender’s body into his own as if by magic. Two shots at the line.

Jimmy rarely makes an individual offensive play that dazzles on the highlight reels. Instead it is his relentless accumulation: basketball as the slow boring of hard boards.

Jordan and Kawhi could be a little like that, but it was different—their final move came as a burst rising up over their opponent, whereas Jimmy’s advantage is gained from the ground, his bit of turf won after a brutal ballet. It reminds me a little of the pear-shaped predation of Paul Pierce. But the thing is—Pierce was an all-time scorer, and this feels a little blasphemous to say—but after the last few postseasons, I’d say that Jimmy at his peak is a more unstoppable offensive force in the playoffs than Pierce was. He has become one of those guys. When elite defenses are dialed in with preparation in the final rounds of the playoffs, you can’t get your normal stuff on offense. You need someone that is impervious to attention and adjustments. Someone who is undeniable. That’s what Jimmy has grinded himself into.

And? Also? He never lost the hustle and tricks of the role player, which Jimmy—a scrappy player picked late in the draft who no one projected as star—used to be. He is still cutting hard, working every angle, hitting the glass, scurrying into gaps on busted plays. He is one of the smartest operators on the floor in the NBA. He is not a natural playmaker, exactly, but he is so quick to reckon where everyone is that he has become a highly effective passer. He seems to take particular pride and delight in finding his teammates in advantageous positions. He’s not the chessmaster that even this year’s old-man version of Lebron is, but he has a little of that flavor in the way he reads the floor and directs the action. He is a relentless player but also calculating, ruthless with his patience and vision. He is stubborn: an indefatigable insistence when the chips are down that he will get a good shot for himself or his teammates.

I’ve mentioned before that his single most elite skill is his incredible energy—what the scouts call his “motor.” Jimmy has another gear, to stick with the metaphor, and he is able to sustain it with a level of endurance that must rank as among the greatest in the history of the game. This applies to his smarts, too. What I mean is that he will play nearly every minute, banging out every offensive position as the lead guard on a limited team and hounding the best perimeter player on the other end—and when those final minutes come, he remains calm and calculating. Watch the end of a game, and it’s usually a little sloppy, because mental fatigue has set in. An athlete can get one last bounce out of dead legs, but mental focus can go slack when the body is wrung out, and mistakes get made. Watch him in the home stretch: Not Jimmy.

It seems like Jimmy Butler would be really good at Risk. In a really annoying way, but it would still be fun to play with him.

I may tell all my bones: they look and stare upon me.

—Psalm 22

My guess is that the Denver Nuggets are going to beat the Heat in the Finals. We’ll see. Game One tips off tonight.

Denver has homecourt advantage and it’s a particularly good matchup for them (Boston would have been something of a nightmare scenario for the Nuggets, who have been relatively fortunate in their draw in terms of the matchups). The Heat are short on defensive options to try to deal with Nikola Jokić and lack the sort of point guard that can really make Denver’s lack of defensive versatility a problem. Aaron Gordon is a pretty good defender on Butler and the Heat simply don’t have much firepower on the rest of the squad (unless Caleb Martin remains a supernova; he managed to not miss a single mid-range shot the entire series against Boston!).

Tyler Herro may be back by Game 3, and his game could poke holes in the Nuggets’ defense, but he’s such a defensive sieve himself that I’m semi-convinced that the Heat are better off without him in the playoffs. The Heat will need to continue unbelievable three-point shooting to hang in this series—probably unsustainable, though a lot of their guys do have excellent track records as shooters even if they struggled at times in the regular season this year. Could happen, but it’s a tough bet against a Nuggets team that is so much more polished and consistent on offense. The Heat will need Jimmy to be the best player on the floor for long stretches to have a chance, but they will also need to have their motion offense humming. Perhaps between their whizzing handoffs and Jimmy pick and rolls with Bam Adebayo, they’ll be able to get Jokić stuck trying to guard out in space, where he’s ineffective and could get worn down (on any nights the Heat win in this series, check the stat line and I’d wager Adebayo has at least five or six assists).

They’ve got a shot. But the Heat will only going to be able to slow down the Nuggets offense so much, and I just don’t think they can score enough to win four times.

The Nuggets are rested, the Heat are exhausted. Jimmy, in particular, seems like he just doesn’t have much left in the tank, and may have re-aggravated his ankle in Game 7 against Boston.

Also, just: Jokić, man. The sheer creativity and audacity of his offensive game deserves its own post. A couple of times a game, he bends our sense of the possible, shrugs, and jogs back down the floor. Circus shots are like layups for him. And you would never guess it from looking, but his conditioning and energy is also elite. He just keeps coming. If he dominates this series, the consensus will solidify that he is the best player in the NBA. Hard to argue with that (though I’d still give Giannis a hearing despite the results in the playoffs this year). Jokić can and should put up cartoon numbers throughout the Finals.

But who knows. The Nuggets are clearly the best team in the West, but the Heat smoked what we all thought were the best two teams in the East. I certainly didn’t think the they could beat the Bucks. I was pretty surprised that they beat the Celtics. And here we are.

Among all forms of mistake, prophecy is the most gratuitous, as a wise woman once said. Be that as it may, I’ll say Nuggets in six.

Godspeed Jimmy Butler, who surely prefers it when people bet against him.

Two exceptional things about Jimmy Butler on the basketball court: his posture--he plays straight up as if he were balancing a pot on his head--and his unmatched gracefulness as he moves on the court.